Last week I encountered a number of photographs in various mainstream journalistic slideshows of the Terra Livre (Free Earth) indigenous camp meeting that took place in Brasilia and where thousands of Indians from numerous Brazilian tribes congregated to demand government attention to indigenous issues. Most of these photographs, shot in middle distance and at oblique angles that put them on display for the viewer, featured Indians dressed in colorful tribal costumes, applying or displaying body paint, playing instruments and performing traditional dances, and the like. Not a single caption mentioned a single indigenous issue nor could I find I newspaper article anywhere that described or discussed the event. There to be seen, there evidently wasn’t anything worth reporting on—or at least writing about.

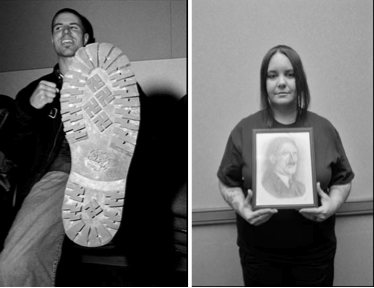

In order to understand this somewhat odd situation we might take account of one photograph that actually stands out from the rest for its apparent critical and ironic appeal. It is a fairly tight close-up of Cacique Raony Kayapo, a member of the once nomadic Kayapo tribe that now lives in the Brazilian rainforests, as he downs a can of Coca-Cola before attending a protest march at the Terra Livre indigenous camp.

The photograph could be an ad for Coca Cola—and indeed, I would not be surprised if I were to see it on a billboard in the near future. Or it could be a critique of western, cultural imperialism (think “The Gods Must Be Crazy”), though that seems less likely if only because the tight close-up and low angle invite the viewer to identify with the scene. But there is another point to be made. For the image also performs—or perhaps neutralizes—the ideological problem at the heart of the tension between traditional society and modern globalization. Indigenous groups like the Kayapo recognize the need to protest against modern concerns that threaten their very survival, such as the building of dams and the polluting of rivers caused by growing gold mining projects, but at the same time they have become “addicted” to the sweet allures of modern society—whether nutritionally empty soft drinks or the technological wonders produced by late capitalism such as satellite television. And as long as one has to have a swig of Coke before standing up to the lords of globalization it seems that the battle is over before it ever begins.

Appearances aside, then, publications of the photograph (and it showed on a number of mainstream journalistic slideshows) function less as an act of visual irony and more as prima facie evidence in support of the globalization thesis itself. No articles accompany the image (or any of the images of the Terre Livre indigenous camp published by the mainstream media) because they aren’t necessary to make the point: whatever “local” issues vex the Kaypao and threaten their ecology, what matters is that they have embraced the economic symbols of western globalization. Seeing is believing. What more need be said?

Photo Credit: Eraldo Peres/Reuters