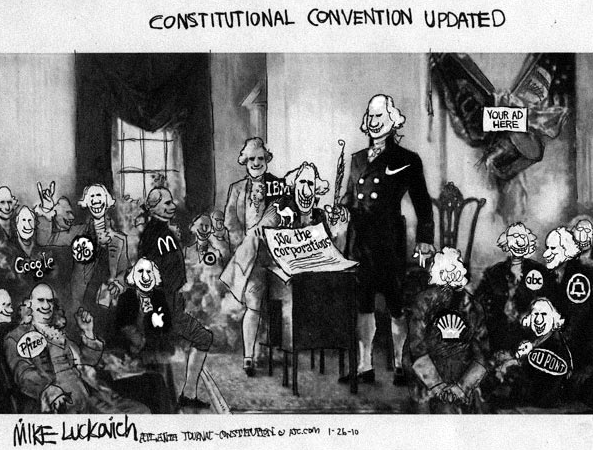

Decoration has been deemed inferior to serious art, philosophy, and political thought since Plato, and especially so within modernity and the aesthetic regime of modernism. In my lifetime, it has been commonplace among educated people to snub some things by labeling them “decorative,” with the term (or its synonyms) designating superficial or excessive display. There is some irony–or not, perhaps–in the same slights reinforcing hierarchies of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, and empire, as there is a robust history of representing people of color, lower classes, women, gays, and subaltern peoples as too caught up in adornment. So it is that one might wonder what is being shown here:

I get a real kick out of this photograph, and not only because the truck would stop traffic where I live. The man’s head sticks out as if the vehicle is a carny show or a clubhouse (though hardly for a secret society), or perhaps the carapace of some kind of exotic social creature that you might find in an art house film. Closer to reality, you have to admit that someone has a lot of pride in that truck, and justifiably so. But even so, it may be too easy to let the image activate the old binaries: those people are exotic (of course) and thus devoted to social display rather than rational analysis and organization, and so necessarily less productive than those of us who would keep our trucks completely functional. To challenge that conclusion, you could point to the care lavished on the chrome pipes and rich paint on many an American 18-wheeler, but we can do better yet by quoting from the photograph’s caption: “A Pakistani truck driver enters a distribution point carrying relief supplies for internally displaced civilians.” The decoration fits right into a scheme of modern administrative organization, and that gaudy piece of folk art is functional after all.

But surely this curiosity has no real utility:

Again, I love the photo for both its eye-catching quality and its sense of strangeness. What is that thing? Well, it’s a giant floral sculpture shaped as if it were itself a flowering plant or perhaps a vase holding flowers, and, for the most part its just too damn big, isn’t it? And that distortion in one’s sense of scale is a key to the photo’s artistry. One can’t be sure whether the man is to provide the measure for the artwork, or the artwork for the man. As in the photo above, the human being is both very much a part of the scene–perfectly at home in it–and yet also dwarfed by the artifice. And as before, the decoration seems completely out of place and yet obviously is completely intentional–just what is supposed to be there and is being carefully tended.

The second photo is from Shanghai, and the caption verges on comic understatement: “A gardener waters plants near a giant flower-shaped sculpture.” I imagine adding, “a giant flower-shaped sculpture that will reproduce across the land and become objects of worship for you pitiful creatures, you humans with your pathetic love of pretty things, your fear of the blank surface and the empty space, your need to be ruled by what delights the eye.” But that would be the modernist talking; ok, a slightly bent modernist, but a modernist.

The philosopher Jacques Rancière distinguishes between two senses of the aesthetic: the traditional idea of it as the modality of the sensible which then is contrasted with rationality, and his definition of the aesthetic as a distribution of the sensible: that is, as both a given arrangement of sensation and reason and an additional disturbance of that relationship that neutralizes the hierarchy and so opens one up to alternative arrangements, including those that seem excessive but are still a part of one’s world.

And that’s why I enjoy the two photographs above. Although they draw on a given distribution of the sensible that denigrates the human mania for decorating the surfaces of the social world, they also trouble that distribution. The photos portray popular and public artistry that is at once trivial and superfluous, but they also capture a combination of familiarity and strangeness that merits attention. Neither the artifacts nor the photos are great works of art, but they suggest that nothing can be merely decorative.

Photographs by Aamir Qureshi/AFP-Getty Images and Nir Elias/Reuters. For a recent summary of Rancière’s argument, see “The Aesthetic Dimension: Aesthetics, Politics, and Knowledge,” Critical Inquiry 36 (2009), 1-19.