Let me be perfectly clear: this post is not a criticism of either China or India. Their economic development, social services, and security measures are hardly perfect, but that is true of every society, not least the one that I know best. The images below are distinctive, however, for at least two reasons: they belie the dominant narratives of modernization and the triumph of capitalism that now define coverage of those nations and many others as well, and they expose a truth about human mortality that is never likely to be carried in the parade of well-dressed shoppers, shiny new automobiles, and gleaming office buildings that otherwise define the Asian miracle and the Indian takeoff.

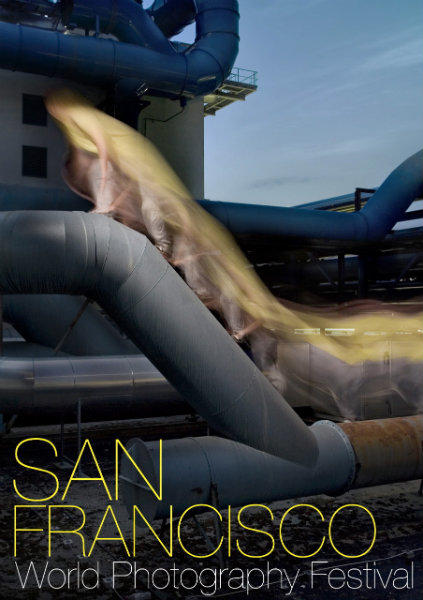

Welcome to the other China, the one where 150 million still live below the poverty line. This photograph of an HIV patient could double as a template for modern poverty. Aluminum and electricity are there, but dented and run in via an extension cord. The daily calendar is there–symbol of the modern work day-but stuck on a wall where it looks like a hospital room number, a sign for a place where time only passes instead of being harnessed to measure productivity. The walls themselves have seen a lot of time pass, as they are old, chipped structures from another era.

Time passes also as our gaze is drawn slowly into the recesses of the room, which becomes an image of stasis. The man is not moving, may not have moved for awhile, may never move again. The pathway goes past the stove, then the bag of rice, then to the man himself. It is hard to imagine him getting up, measuring and cooking the rice, and walking out the door. The low-grade disorder of the table and bed is just one notch above the almost complete inertia of the scene as a whole. This is not an image of dynamic progress. The future may be bright, but in this case it is not likely to arrive in time.

And here is certainly is too late. One police officer accompanies another who was killed in a shootout with insurgents in Srinagar, India. Some hint of the vibrant street life of the subcontinent is evident outside the van, but, again, this is an image about an interior space. Although ringed with windows, the van is almost a small, funereal world onto itself, a temporary tomb for one dead body and another in waiting. And, again, the shabby seats seem to confirm the overall inertness of the place, as if nothing ever really changes there.

Others can see into the van, but the man seems to be staring blankly, as if lost to inward reflection. He has reached out a hand as if to steady the corpse, but it may be a last gesture of connection taken to steady himself inside. A gesture not evident in the first photo, but one that can be made by the spectator, were we to take the time to reflect on what is being revealed.

Political violence is the low-grade disorder affecting the Indian nation–and many more as well–and its alignment with stasis in this image is another sign of the persistence of violence within modernization. Gandhi called poverty the greatest violence, and it, too, seems to persist all too easily within modern development. Closer to home, all the marvels of the modern world will not save any one of us from death or from the isolation that can precede death. Whatever the date, at the end of the day we all end up behind the facade of modernization. As that is so, perhaps we might do more to reach out to those already there before us.

Photographs by Reuters and Altaf Qadri/Associated Press.