Pop Quiz: One woman or two?

Or was it a trick question? There obviously are two women there, even if one is a copy of the other. And if you look closely, you can see small differences in hair or the accessories in the background or whatever else you want to pore over. But, of course, there also is only one woman there: a blond archetype of American femininity that is the model for each of these two Miami Dolphins cheerleaders.

The two bodies could almost be clones. And, of course, they are: not because they share a fair amount of genetic material, but because each is an near perfect copy of a social form. Each is identically styled to that conventional model, from physical training to gestural habits to costumes and make-up. Each will stand out because she so completely conforms to one set of social norms. Together they mirror not only each other but their society’s demand for conformity.

But don’t think that style is to blame. Or at least consider the other end of the spectrum:

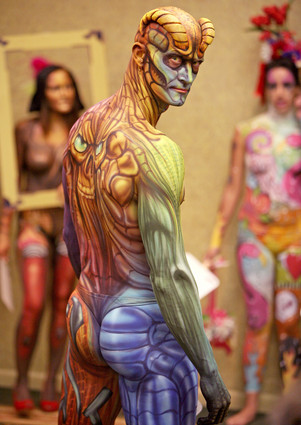

There is only one of this guy, right? He is a model at the annual Face and Body Art International Convention. Who else could possibly look like this? (The style is the man.) But, of course, he is not so unique. He fits right into the body art subculture, and the artist is drawing on familiar conventions of mythic iconography and popular design. Just in case that context isn’t clear, notice the Mona Lisa figure in the left background. And, like the cheerleaders, his well-toned body is a standard typification of gender.

The cheerleaders train for hours to have a few minutes of spectacular performance, all at considerable cost to themselves and other women. Mr. Body Art is a model of self-fashioning, but only for a few hours in a convention center that tomorrow will be hosting Rotarians while he becomes just another guy on the street. Fashion alternates between conformity and unique self-assertion, and each depends on the other. Most of us spend our time between these two extremes, but we shouldn’t feel too smug about that. Among human beings, there are only differences of degree, never of kind.

Photographs by Abbey Drucker/VMAN Magazine (October 2008) and the Orlando Sentinel, and Vince Hobbs/Orlando Sentinel (2009).