Notwithstanding the oratorical skills of Lady Gaga, the U.S. Senate voted today to block debate on a bill designed to repeal the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. It might be easy to lay the blame on the forty Republican Senators, bolstered by two renegade Democrats (plus the majority leader whose vote was a procedural ploy that allows him to reprise the bill at a later date), who voted against letting the bill come to the floor for debate, but that would be to ignore any number of complicating issues, such as efforts by the Democratic majority to add contentious amendments to the bill concerning immigration policy. All of which is to say that its not exactly clear what specific interests were being served here on either side of the aisle.

One might imagine this as standard operating procedure for a legislative body that seems intent on letting partisan political self-interest stand in the way of national interest, and hardly worthy of note but for the presence of Lady Gaga. What is interesting here is how the national media has given significant attention to her ersatz protest rally without fully recognizing the way in which her transparently self-conscious spectacle is not just an appeal for the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” but is also (and maybe more) a parody of the mass mediated political process itself. To get the point, notice how many if not most of the reports on her rally are primarily if not exclusively photographic, almost to the exclusion of any consideration of what she actually had to say. The irony, of course, is that a quasi-faux rally cast as political spectacle received far more coverage than the presumably unintentional spectacle of actual Senators deciding the fate of the military.

Perhaps the most interesting representation of the Lady Gaga rally occurred in the pictures of the day slide show at the Washington Post. Despite the possible significance of the Senate filibuster on the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, the pictures of the day at WAPO feature a photographer at a photo fair in France trying on a pair of 3-D glasses, a child in Slovenia sitting next to his friends on a curb and with a bucket on his head, and Bristol Palin displaying her legs in a PR shot for the television show “Dancing with the Stars.” There are no pictures regarding the debate over gays in the military. Or at least not at first glance. But as one moves through the thirty seven images in the slide show one eventually comes across the above photo of Lady Gaga, public advocate, characterized as “rail[ing] against what she call[s] the injustice of having goodhearted gay soldiers booted from military service, while straight soldiers who harbor hatred toward gays are allowed to fight for their country.” The alternative she prefers, we are told, is to “target straight soldiers who are ‘uncomfortable’ with gay soldiers in their midst.” That the caption fails to acknowledge either the irony or the parody of Lady Gaga’s performance is underscored by the two photographs that follow.

The first of these photographs shows a “former” member of the Air Force taking a picture of the rally.

Perhaps he is one of those “good hearted gay soldiers,” but nothing in the photograph suggests as much. Indeed the photograph suggests incoherence as much as anything. Shot in long distance we see only his face and hands as they peek up from behind a poster to take a picture for Twitter of the anonymous and faceless audience waving hands. The background shows a large American flag, but its meaning is made ambiguous by the somewhat incomprehensible legend on the poster that implores the audience to “Leave them Speechless.” Lacking any reference to context, the overall effect of the photograph is one of clutter and confusion. And as a result, the political and parodic effects of the rally are muted, or worse, made to appear senseless.

It is the second photograph, however, that by contrast politicizes the slideshow, suggesting an antidote to the apparently incoherent spectacle of Lady Gaga’s rally.

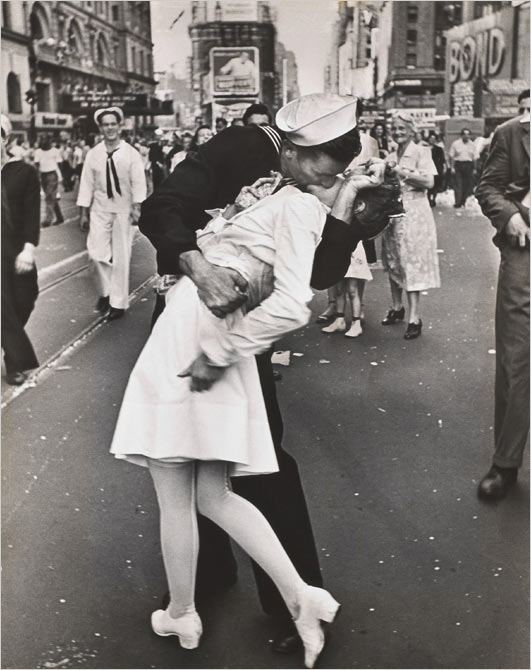

Here we have a member of the Army National Guard preparing to leave for a training assignment in Texas and a subsequent deployment to Iraq. Shot in medium close-up, a soldier (not a “former soldier”) and his wife say goodbye. It is a tender moment. The two lovers gaze into each others eyes as he offers solace by placing his left hand on top of her right wrist, while her right hand gently supports her chin in a gesture that suggests a degree of vulnerability. It is hard to tell if she is smiling or crying, and probably she is doing a little of both given the stresses and strains of the impending separation. He is apparently “straight,” but it is hard to imagine him harboring “hatred” towards anyone, let alone why he should be “targeted. Indeed, though this is a scene of separation and not reunion, and while he is not a sailor nor she a nurse, one can nevertheless imagine them embracing in Time Square to the nodding approval of the public that views them.

And therein lies the problem. For what gives this photograph its affective power is the way in which it visually repeats the conventions of the famous Times Square Kiss. It not only foregrounds traditional, heteronormative assumptions, but it does so by valorizing a private moment in a public space. Of course there is nothing especially new here. We have long sought to manage our anxieties about war and the military by normalizing our understandings in the context of a sentimentalized heteronormativity. To get the full effect, imagine two men or two women in the same pose. And, that, of course, is the point. Don’t ask, don’t tell.

Sentimentality, it seems, trumps parody … or at least in this case. But in truth, both scenes are media spectacles that demand more careful attention than the tired and nonchalant glance they are too often given by contemporary media.

Photo Credits: Joel Page/Reuters, Pat Wellenbach/AP, Joe Jaszewski/AP

Crossposted at BagNewsNotes

5 Comments