The most noted victim of last week’s failure to vote on the Defense spending bill was the rider designed to rescind the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. But no less victimized was the bi-partisan “Development, Relief, Education for Alien Minors Act” aka the “Dream Act.”

Originally proposed in 2001 and more recently revived in 2009, the act addresses the plight of the nearly 65,000 undocumented alien minors who complete high school each year, and yet have no viable route to citizenship. While technically “illegal immigrants,” these individuals came to the United States because their parent or guardian brought them here, and thus their legal status is not something for which they are directly responsible. It is thus extraordinarily inhumane to deny them any access or avenue to citizenship. The Dream Act would make it possible for such individuals who have been in the U.S. for at least five years, who demonstrate “good moral character,” and who complete two years of college or spend two years in the U.S. military to apply for permanent citizen status. It would also make them eligible for student loans.

The photograph above, which shows a group of students who are also illegal immigrants spelling out the word “Dream” in South Beach, Miami, in an attempt to sway the vote of Republican Senator LeMieux. Their protest caught the eye of the New York Times, who printed the image, as part of its story on the run-up to the Senate vote. But what the story missed was the rhetorical import of the playful quality of the student’s effort to create a “human billboard.” This was not just a stunt pulled off by students that had nothing particularly better to do with their Sunday afternoon; rather, it was a concerted effort borne of the recognition that they had no legitimate, recognized voice in a policy debate that directly implicated their future, and thus it warranted staging a protest in a register that would allow them to “speak.”

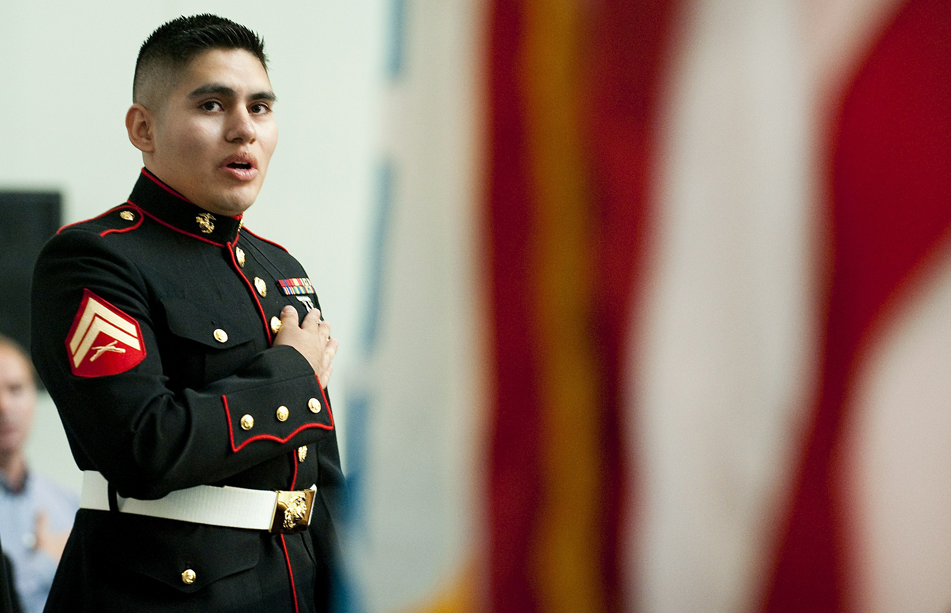

In some important ways the photograph below, which appeared as a random photograph in a recent Wall Street Journal slide show, comes closer to the mark in indicating what is at stake in the failure to vote on the Dream Act.

Marine Cpl. Pablo Olvera, “originally of Mexico,” according to the caption, leads a group of newly naturalized citizens in the Pledge of Allegiance at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. His eyes are fixed on the flag that stands in front of him and shrouds more than half of the frame of the image, almost—but not quite—dominating the field of vision. All the viewer can see are the red and white stripes, but Olvera’s dress blue uniform completes the nationalist color scheme and thus renders the photograph as a literal embodiment of the flag—and thus by extension, the nation itself. And more, the shallow depth of field that focuses directly on Olvera renders a soft, gossamer quality to the red and white stripes that drape his field of vision, evoking a soft, (American) dream-like consciousness.

It is not unimportant, in this context, that Olvera is identified as “originally of Mexico,” a characterization that muffles his otherwise prior illegal or undocumented immigration status, just as the characterization of him “leading” the Pledge implies the kind of moral virtue (or “good moral character”) that we affiliate with civic republicanism. Once “of Mexico,” he is now “of” the United States.

One might be inclined to see this photograph as a melodramatic sop for American exceptionalism, or worse, as a wink and a nod to the idea that we can easily fill the ranks of our “all-volunteer” military with immigrants. And we should not be too quick to reject these implications of the image. After all, the U.S. Defense department is a major supporter of the Dream Act, and it is hard to believe that their endorsement would be driven by anything other than simple self interest. But at the same time, the photograph is a reminder that some immigrants (at least) are willing to pay their own freight to become U.S. citizens, to realize the impossible dream, and that is an attitude we should respect.

It is time that we moved beyond the political wrangle and put the Dream Act to a vote.

Photo Credit: Oscar Hidalgo/NYT; Jim Watson/Agence Fance-Presse/Getty Images