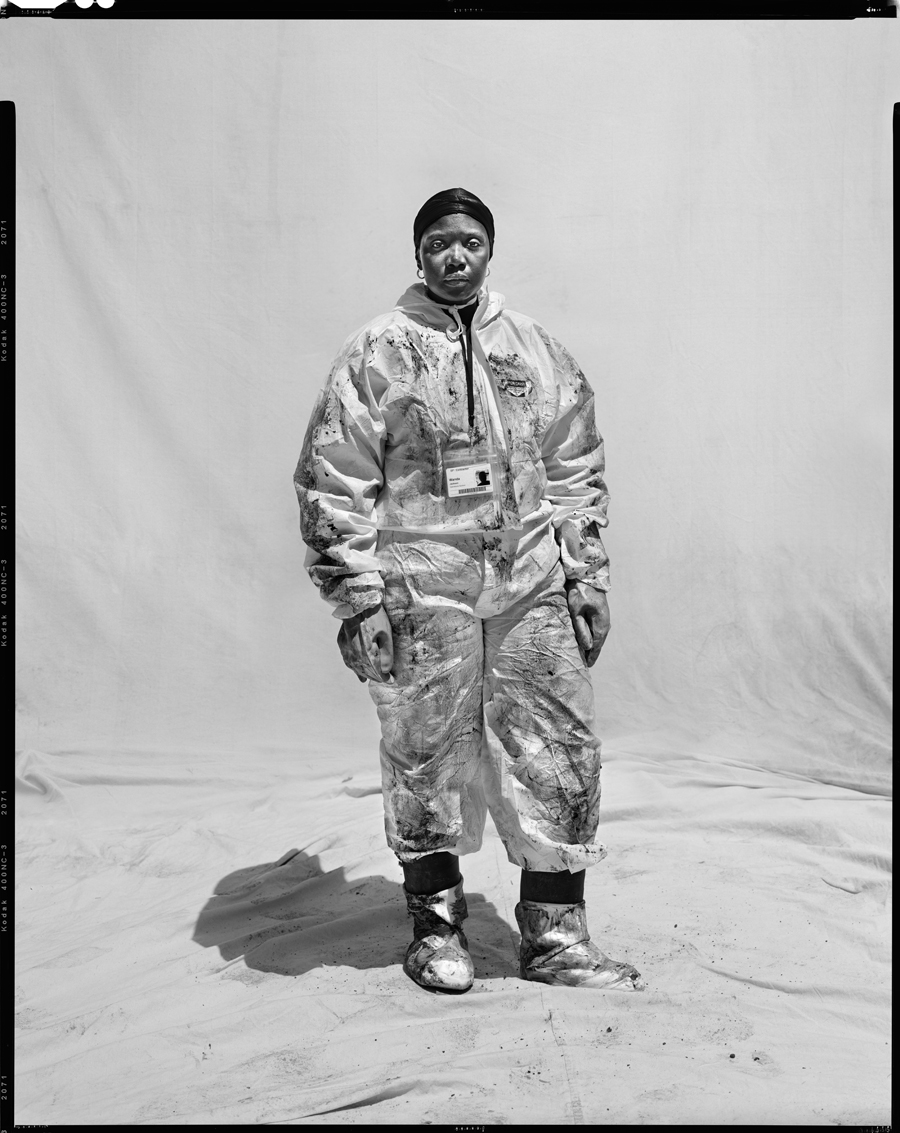

The protests by environmental activists at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Cancun, Mexico last week ran the full gamut of street theatre: signs, costumes, body painting, effigies, nudity–you name it. The image that caught eye, however, was obviously static and even inanimate.

Greenpeace has positioned replicas of some of the world’s iconic sculptures and architectural monuments to suggest one of the sure consequences of global warming: the rising sea levels that could conceivably submerge coastal cities. Obviously, some creative license has been taken, as no one outside of a bad B-movie studio is going to suggest that the Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio de Janeiro is likely to get wet–its base is 2300 feet above sea level. But in any case, we’re all in this together, right?

Well, yes, actually. These iconic images provide a shorthand for relaying messages and activating emotional attachments within a global civil society. Cancun is not known for its public monuments, so this display is one way of bringing the world to Cancun. It would persuade few to point out that the buildings in the background might be flooded someday, but the Sidney Opera House would be a loss that might touch those who care about culture. Seeing the several icons sharing a common fate of being reclaimed by the sea suggests that national interests should be united by global warming. More important, the scene suggests a common public interest, represented by a shared public culture known in part by its visual symbols. Left to themselves, they symbols are shown to be defenseless against the predictable consequences of unregulated exploitation of another common resource: the global ecosystem.

We get that, I think, and we were supposed to get it. But there is something else in the picture that also bears comment. Here I refer to the somewhat shabby tone of the tableau. Amidst the tropical ocean and gleaming beachfront resorts, the figures look out of place, off-kilter, as if they had been discarded. Instead of consolidating their symbolic powers, they have been diminished, as if hollow effigies deserving only fire sale prices. Instead of rightly adorning world cities, they could be in backlot storage for a Hollywood studio. “Where did you put the icons, Eddie?” “Those things? I got ’em out in back, in the containment pool. Why? You get an offer for that junk?”

And what would you pay for a damaged icon?

The collapse of the roof of the Minneapolis Metrodome got a lot of press yesterday, even though it wasn’t the first time that snow has caused the roof to deflate (yes, that’s the term that is used). No one was hurt, the scheduled football game has been moved to Detroit, and the structure would have had little use anyway, so what’s the fuss? Obviously, the damage is one measure of the impact of Saturday’s snowstorm, and, as with the Greenpeace protest, another signature building became a symbol of how society cannot avoid the consequences of ignoring nature.

What interests me, however, is how this photograph, like the one above, captures a sense of shabbiness. Actually, the Metrodome is never far from vernacular life, as even on its best days it looked like a Marshmallow that one might see around a Minnesota campfire. (That lack of elevation is one of the things I love about Minnesota.) Even so, the deflated stadium looks like a cheap backyard pool or hot tub poorly protected against yet another winter. Or, if compared with the Minneapolis skyline in the background, like some decrepit structure in an old industrial park, say, where the pork by-products used to be processed.

Rather than assume this shared mood is accidental, perhaps one might consider how the photographers have captured something important about public culture. Monuments to civilization are not self-sustaining, and engineering marvels need to be well-designed and well-maintained in respect to environmental challenges, and even then can fail. Civilization itself is something that is not automatically sustainable, and modern societies create particularly complex equations that may include only a thin barrier between progress and catastrophe. It doesn’t take long at all for any modern building, city, or society to look rundown, past its best days, trapped now into cycles of decline. All that is needed is enough denial or inattention. Against those tendencies, these photographs suggest how close the present can be to a future of decline.

Photographs by Eduardo Verdugo/Associated Press and Carlos Gonzalez/Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

0 Comments