Best Wishes to our readers for a pleasant holiday break. NCN will begin posting again on Monday, January 4.

Photograph by Francois Mori/Associated Press.

Best Wishes to our readers for a pleasant holiday break. NCN will begin posting again on Monday, January 4.

Photograph by Francois Mori/Associated Press.

“I have been a witness and these photographs are my testimony.” James Nachtway

‘Tis the season for the multiple lists of photographic retrospectives. The first to cross our in-box include this special issue from Time magazine that begins with a introductory letter from Richard Stengel titled, “A Window on Momentous Events.” We will list additional retrospectives as they become available, so keep coming back to check in over the next several weeks.

Additional Retrospectives: Big Picture 1, 2, 3, Pictures of the Decade; NYT; NYT-Documenting the Decade; AOL: The People’s Choice, Editor’s Choice; LA Times; Charlotte Observor; Washington Post: Best of the Decade, Best of 2009; Chicago Tribune; Wall Street Journal; New Yorker

The war in Iraq and Afghanistan is slowly edging back into US public media, but it’s still easy to miss. The problem isn’t only that so much attention is being given to the debates about health care (or the lack of it) and financial regulation (or that lack of it) and the continuing problems in each sector (see “lack,” above). The war coverage itself has a peculiar cast: instead of deployments, patrols, firefights, and other action shots, there have been a stream of images that show wreckage, rubble, and similar scenes of destruction. Scenes like this:

A man walks slowly along Cairo Street in Baghdad in the aftermath of a bombing. The bomb obviously was huge, leaving a vast swath of mangled metal and broken lives. What you don’t see is a field of battle; instead, this is a civilian street, complete with a cobblestone median and an institutional building in the background. The picture might be said to lend plausible deniability to the idea that there still is a real war going on in Iraq. The lone figure in the foreground suggests as much. He is every inch a civilian, and his pensive posture suggests that this is a time for reflection, not action.

The flag is still flying, and officials and soldiers far in the rear will oversee the clean-up, but the large space between them and the lone individual in the front is empty of people, as if the society itself had been vaporized in the blast. The war is there but not there, while the social, ethnic, religious, and political motivations for the bombings are unintelligible. A bomb detonates, and a man muses. Apparently, there is nothing for him–or anyone else–to do but to walk on into the unknown future that lies outside the frame. Like this:

There have been dozens of photographs similar to this one in the past several weeks: photos of US troops standing around or slowly walking through places that are otherwise empty. Often enough, they are scenes of destruction, but the act is already in the past, something that occurred off camera. The troops aren’t fighting so much as overseeing an impersonal process of destruction. And that process seems to involve razing city streets and vehicles more than anything else; again, the people that would normally fill the scene have been ghosted away.

Note the many other similarities with the first photo. Again, officials hold down the rear of the scene, while a single person walks toward the space to the right of the frame. His mood is not identical to the man above, but he does seem both turned inward and weighed down, and, again, there is nothing to be done about what has happened. He is merely going through the motions to “secure the area”: an area already secured by the scythe of the bomb’s blast.

Such photos may reflect that fact that US policy has been in a state of limbo for the past few months, but they also may suggest that the US war effort has become something like a permanent state between war and peace, an intermediate place of suspension and neglect. Worse, they may suggest that this is acceptable because the US troops are just passing through. They are there for awhile but not really doing much, and eventually they’ll rotate out and leave the place to its fate as one of the boroughs of rubble world.

And so there is reason to look at the first photograph again, for there may be an important difference between the two after all. Despite his ability to do much more than walk through the scene, there is little doubt that he lives there. If that isn’t his street, it’s his city; if not his city, it’s continuous with where he does live. He thinks, smokes, and walks on, but his future will be in that place. And to see him there is to see someone who belongs in the photograph, whose presence speaks to something valuable there, and who provides a point of contact for the viewer. To the extent that we can see him as being in the picture, we are pulled into the frame as well, and asked to witness and reflect on what is there and why.

By contrast, it seems very clear that the soldier is just passing through. Whatever his presence may provoke, the message is that he really isn’t a part of the scene. If we walk with him, it’s to appreciate his wish to get through it alive, but not to stay in, understand, and commit to that place.

Each photograph–any photograph–presents the viewer with a choice about how much one might be in the picture. In both of these two photos, the choice to the US viewer is skewed toward minimal involvement: one figure is a foreign national in his homeland, and the other is a US soldier far from home. Even so, the first image may also evoke a compassionate response. With the second image, however, it’s just a matter of time before we can pretend that there is no one there.

Photographs by Ahmad Al-Rubaye/AFP-Getty Images and Reuters (Wall Street Journal).

On Saturday 15,000 Christmas wreaths were placed on the graves at Arlington Cemetery. The annual event is an occasion for both press coverage and personal visitations, as with this photograph of a woman hugging the gravestone of her husband who recently had been killed in Afghanistan.

This photo is one of a series of similar shots that together received wide circulation, including the front page of the Sunday New York Times. Some are close cropped while others show more of the surrounding phalanx of gravestones, but all feature the woman holding on to the lifeless stone.

He was 41 when it happened, a Lt. Colonel on his second deployment to the region (the first had been in Iraq). He had been training Afghan soldiers until his vehicle hit an IED. You can read more about him here, but that is not really what the photograph is about. It’s about her, and her devastating loss, and about having to live with that pain and emptiness.

She wraps her body around the stone, trying to get as close as she can to his memory, his still lingering presence, to what they once had together. Head bowed in grief, she knows all too well the futility of living flesh finding warmth in the inanimate object, but she holds on anyway. Who would want to let go?

Her body humanizes the stone, reminding us that there once was a person in place of the block letters of a name, just as her personal act of devotion redeems the rest of the scene, where long rows of bare markers stretch into bone-white desolation. The stones are but symbols, we realize, of those who were loved and lost, and of how much grief must be locked up in those still living.

Some people believe that such images shouldn’t be shown, but they are. They carry no direct bias as they can serve arguments both for and against war, and all might agree that they shouldn’t be “politicized,” but it is hard to pretend that Arlington should lie outside of public concern. Public grieving is an important part of democratic life, and images of individual loss are one of the means by which grief is made intelligible in a liberal society. Seeing how grief isolates people, leaving them so radically alone, might be an important reminder of how the community needs to help those in need, and to sustain its own bonds of collective support.

That said, photographs marking a relationship between private loss and public life also can prompt questions about the relationship between past, present, and national priorities. Have we seen this before? Is the unique moment of individual loss part of a larger pattern? In spite of sincere ritual observances (such as the laying of the wreaths), are we becoming too accustomed to war and the costs of war? How well are we caring for the widow and the orphan, and for all citizens? How much will history have to repeat itself before we notice that, whether in war or peace, the pictures are all the same?

Photographs by Win McNamee/Getty Images and Anthony Suau/Denver Post. The second photograph was taken on Memorial Day, 1983 and received the Pulitzer Prize in 1984.

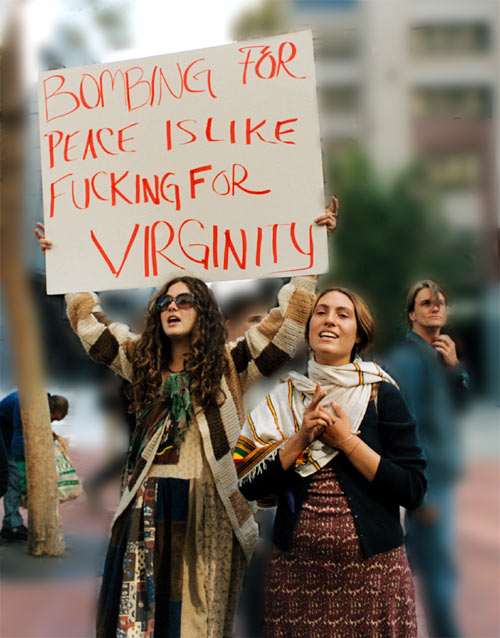

This is a reprise of our Sight Gag of February 17, 2008. If our word processor was working properly the title would read:

“Iraq Afghanistan v. Vietnam – ‘Déjà vu All Over Again’ (Again).”

THEN

NOW

“Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Urban Cuts: Appropriation and Resistance in the American City

The Department of American Studies at Saint Louis University invites papers for its Second Visual Culture Graduate Student Conference, to be held April 16-18, 2010 in St. Louis, Missouri. This year’s conference theme, “Urban Cuts: Appropriation and Resistance in the American City,” coincides with the “Urban Alchemy/Gordon Matta-Clark” exhibition at the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts, St. Louis.

Proposals are welcome from all disciplines exploring visual representations of conflicting uses and contested meanings of urban space. Taking a cue from Matta-Clark’s “cuts,” we seek contributions addressing the effects of changes in urban geography on people’s daily lives. We are particularly interested in projects that examine the role of photography, film, advertising, fine art, performance, architecture, design, and/or new media. We encourage submissions by graduate students working transnationally and comparatively on urban environments.

Topics may include, but are not limited to, the following themes:

– Representation & Iconography of Urban Space

– Demolition, Destruction & Displacement

– Fractured/Fragmented Space

– Contested Ownership

– Political Activism through Urban Space

– Memory & Subjectivity

– “Anarchitecture” as concept and practice

– Abandonment & Neglect

– Urban Renewal

– Urban Performance as Resistance

Please submit a 250-word abstract and a curriculum vitae by January 15, 2010 to vcc2010@slu.edu.

Additional information is available here. For questions, please contact Elizabeth Wolfson (vcc2010@slu.edu).

One of the primary anxieties of late modern life is modernity’s gamble, the wager that the long-term dangers of a technology-intensive society will be avoided by continued progress. And, as with any wager, it is driven not only by calculations of probability but also by an unrelenting desire to beat the odds There is perhaps no better representation of the anxiety that has attended modernity’s gamble than the dialectical tension animated by the iconic photographs of the tragic explosions of the Hindenburg and the Challenger: the first a dark, gothic, dystopian warning against the excesses of technological hubris, the second a bright and forward moving, utopian celebration of the heroic frontier spirit.

I was reminded of modernity’s gamble when I came across the above photograph of the recent public unveiling of the “VSS Enterprise,” named in honor of U.S. and British naval vessels, as well the “Starship Enterprise” of Star Trek fame. The VSS Enterprise is the first commercial passenger spacecraft that will offer 300 paying customers a two and one half hour suborbital space ride—including five minutes of weightlessness—for the modest sum of $200,000 each.

The first thing to recall when considering the Hindenburg and Challenger explosions is that the events leading up to the tragic moment in each case were orchestrated as media spectacles. And note that here too, the “unveiling,” which takes place in the Mojave dessert and in the dead of night, accompanied by “dreamlike purple lights” and “an ethereal soundtrack,” is heavily attended by the media dutifully recording the event. But the comparison does not stop here, for as with both the Hindenburg and the Challenger, the development of the VSS Enterprise has been beset with one technological delay after another, as well as with tragic injuries and three deaths following equipment failures and explosions. We can only assume that more will follow. And yet, the fetishistic desire to conquer the heavens never seems to die, a point driven home by the billionaire Richard Branson who noted, “Isn’t that the sexiest space ship ever?”

These similarities notwithstanding, it should be recalled as well that both the Hindenburg and Challenger were statist enterprises driven by a martial spirit and distinct militaristic goals—the Hindenburg underwritten by Hitler’s Nazi Germany and an interest in exploiting the advantages of air warfare, and the Challenger a manifestation of the U.S.’s involvement in the Cold War “space race”—while the VSS Enterprise is an entrepreneurial, free market enterprise. This difference, it seems, is worth remarking upon, for while one might imagine militaristic functions as part of a “rational” public policy agenda, the current enterprise seems driven by the same hubris that led Icarus to fly too close to the sun, and one can only assume that the current “enterprise” will have a similar ending. How else to account for such space tourists as Natasha Pavlovich, a native of Serbia who bought her ticket “on credit” because she wants to “bring pride to her native country.” In short, the fetishized, ritualistic thrill of modernity’s gamble comes in many guises, and the desire to “beat the house” is an unyielding addiciton for indivduals and states alike, regardless of how tragically fated its failure it might be.

It is little wonder, then, that agencies like NASA stay in business and that the citizenry is willing to support them with public dollars. Or that the media is always there to play its part. Yogi Berra had it right.

Photo Credit: Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images

Lawrence Olivier once suggested that the key to acting was throwing yourself into your part, no matter that it might be as insignificant as the third spear carrier from the left. The characters in this scene exemplify that advice.

While the figure on the right stands guard, the figure the left picks up body parts in the aftermath of a suicide bombing in Islamabad, Pakistan. Neither action is likely to be decisive in the war spreading across that country, and each seems incidental even within the small scale of this photograph: the tiny pieces of flesh being retrieved appear to be no bigger than a fingernail, while the soldier is armed and ready in a street that is once again stabilized, even static, and almost empty. Yet they are playing their parts with complete concentration, as if the play really mattered.

This play does matter, of course, and yet the war there and in Afghanistan is haunted by the sense that a deadly serious game also is being played merely for show. The full panoply of state action appears, albeit too late to save those who were attacked, and on behalf of the restoration of a normalcy that was already a facade. Everything in the scene is meticulously modern: sharp uniforms, aluminum signage, yellow plastic crime scene tape (in English), even the flowers in the traffic median and the clear plastic gloves for the body-part detail. And yet none of these investments in civic order could keep someone from detonating a bomb among innocent people.

Thus, the image is troubling because of how it captures several deep tensions within state responses to insurgencies across the globe: tensions between attentiveness and incapacity, between restoring civic order and refusing to change, between collecting the dead and ignoring the demands of the living.

Because they have played their silent roles so well, these two minor players allow the scene to speak. The photograph depicts another instance of the normalization of violence in the 21st century. Nor can that violence be attributed wholly to the absent suicide bomber, for every part of the mise en scene declares that such violent acts are not a primitive residue, but have become fully integrated into a ritualized modernism. Unfortunately, it seems that too often the modern state is committed only to maintaining whatever imbalances feed its own display of power. If so, then any show of strength really is a sham.

Photograph by Adrees Latif/Reuters.

Credit: Fox News, Chicago

“Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

Une histoire photographiée de l’occupation israélienne 1967 — 2007

(A Photographic History of the Israeli Occupation, 1967-2007)

Curated by Ariella Azoulay

Centre de la photographie

Geneva, Switzerland

ACT OF STATE is the first photographic history of the occupation of the Palestinian territories. This exhibition documents both a history of facts and a history of representations. The 700 photographs taken by 50 photographers are printed on A4 sheets from digital files. The images also are available in an Italian catalogue published by Bruno Mondadori in 2008.

28, re des Bains, Ch-11205, Geneve

t +41 22 329 28 35/F +41 22 320 99 04

epg@centrephotogeneve.ch

December 3, 2009-January 17, 2010

Photograph by Rina Castelnuovo, 1997. See also Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography.