We’ve seen it before.

I’ve even posted on it before. Not exactly the same photograph, of course, but one very much like it. Suicide bombings are on the rise in Iraq again, and so the news returns to the same crime scenes, the same wreckage, the same helplessness. The news that, like much else that was needed to prevent the bombing, arrives too late.

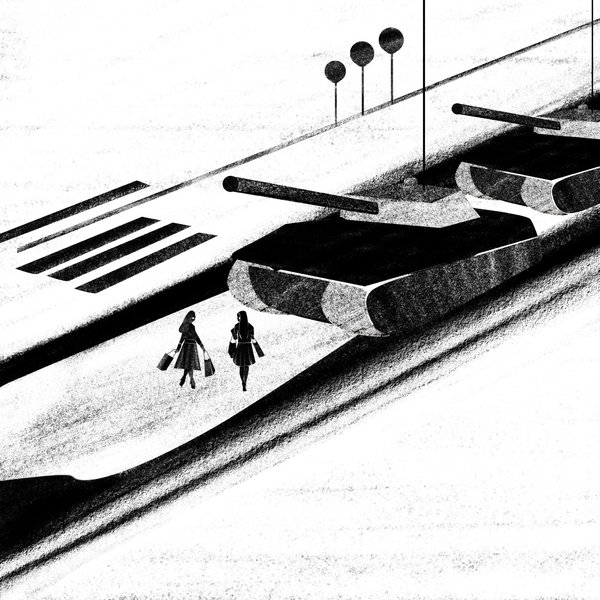

Maybe that guy in the cameo is an official of some type, and maybe the state has something to do–a bit of forensic work, perhaps, and some record keeping. To me, he looks more like the guy with the tow truck, and the only decision to be made is how he’s gonna get that metal carcass up on the flatbed. As for the rest of those present, well, what can they do beyond what they are doing? They mill about aimlessly, look for the odd remnant, look around to see who else is there, try to take in the scene as a whole (but what is that?), and generally rely on their presence and the passing of time to somehow bring the world that was there before back into focus. What else would you expect? After all, they are spectators.

Spectators like us. Another bombing, another photo of its aftermath, another moment where you arrive too late to be reminded that there is little you can do anyway. And what did you expect? The photo does not make an emergency claim–there are no ambulances, no heroic first responders, no valiant citizens resolved to fight on. Instead, we see trauma reduced to curiosity as a society, for want of any other option, returns to something like normalcy.

Nor does the photo make a call on our compassion or any other strong emotion. Instead the scene is emotionally diffuse, even deadening. Any dramatic actions or reactions are off stage. In their place is stasis, inaction, banality. The photo shows us how few options ordinary people have when living amid violence. The question remains, are the options any better for the person viewing the photo?

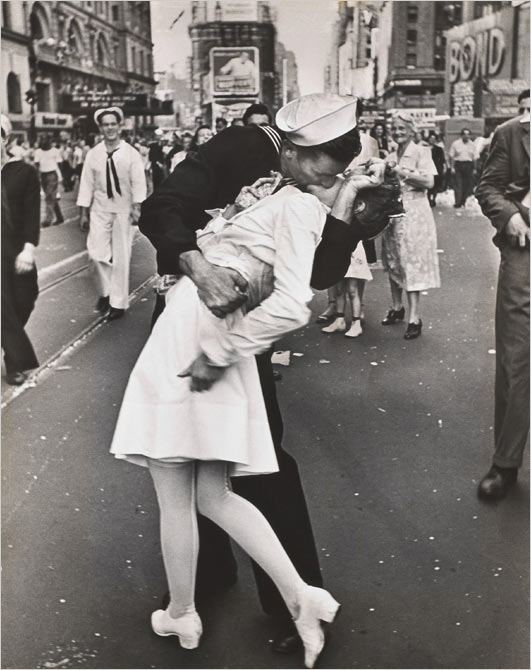

By this point, many writers would have laid the blame for any inability to do much else on the medium of photography. We’ve been told far too often that it makes us into voyeurs or tourists and exhausts or perverts our moral sense. That could be true, although frankly I think you are safe. Let’s consider instead how the photo from Baghdad is doing something else.

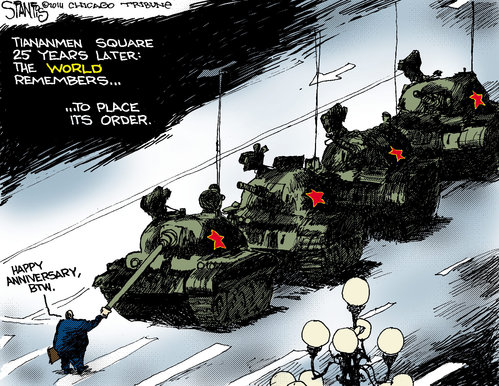

It’s not a great photo; it may even be unusually flawed, unless you can tell me what that inchoate white column is in the middle of the main vehicle. But that doesn’t matter. Whatever its “quality,” the photograph is a worthwhile realist statement: first, because of how is it one of many like it, all of them keeping the war visible–and I mean the war, not the abstractions that fuel it. Second, it shows how large-scale forces are experienced by ordinary people: experienced, that is, as disasters and as ongoing disruptions and as events that will never make sense even as everyone becomes more or less accustomed to coping. Third, it reminds us that spectatorship alone is an insufficient basis for an effective response to what is shown.

And I’m not just talking about the spectators in the photograph. If photography is to confront violence, speak truth to power, or meet any other noble aspiration of the public media, it has to be linked to audiences and organizations who can act where it counts. That may be in the legislature or the refugee camps or a thousand other places, but we have to be able to imagine doing something and then work with others to the same end. Photographic realism works through spectatorship, but the objective is something more organized.

As far as Baghdad goes, I don’t know if any good options are available within the city or elsewhere in that country. It may be that the photograph is disturbingly realistic, in the sense that it implies that there is no basis for those in the picture to organize themselves against the next bombing. They seem to have nothing but the inadvertent associations of a crowd at the scene of an accident. There are political and military organizations offstage, of course, but they are the problem, not the solution. In a photo of the aftermath of a bombing, there may be even less to see than we had thought.

As far as the US or other countries that are or could be involved, well, we each need to look in the mirror. The problem is not what is or is not being shown, but whether there exist any political organizations capable of doing what is needed to move from war to peace.

That said, one symptom of a lack of solidarity or political efficacy is that people acquire a habitual blindness on some topics. Topics like war, for example. When you’ve seen it before, and since there is nothing you can do, it’s easy not to see it again. And then the destruction and despair are sure to continue.

Photograph byKhalid Al-Mousily/Reuters.