Guest Correspondent: Brandon Thomas

There is no shortage of potent imagery from the Gezi Park movement, which has evolved into a pseudo-1960’s around-the-clock “Be-In” where spaces and resources are shared communally. Though victorious and celebratory, the police-free zone that currently surrounds Taxim Square still carries the scars of the weekend’s turmoil. Overturned cars have become in situ art installations. Vendors peddle corn, simit, and beer on the streets. One bus, its windows smashed out, has been repurposed into a library. And every day thousands of supporters, revelers, and tourists make the pilgrimage to what has become the epicenter of Turkey’s biggest peoples’ movement in years.

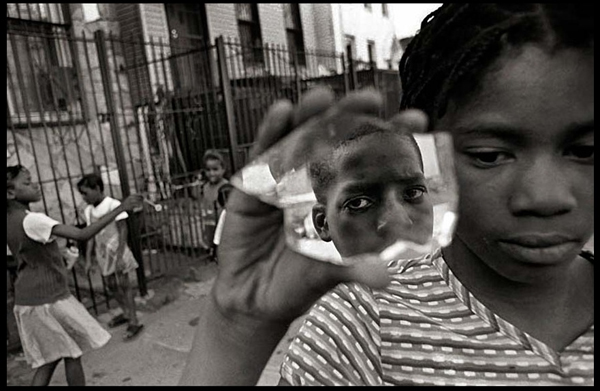

In many ways the protest today is unrecognizable from the sit-in it began as in the last days of May, before the bulldozers, riot gear, and international attention. Despite this, a photo produced on the fourth day of the protest has emerged as the movement’s first signature image. Dubbed the woman in red by Alexandra Hudson of Reuters News Service, the picture immediately went viral in Turkey before being snapped up by multiple news agencies and acclaimed by many as the symbol of Occupy Gezi.

What is it about this image that makes it so compelling? Looking at the key elements in the frame, we see two people, a male police officer with a gas mask and a hose that appears to be spraying a female with what we surmise is pepper spray. Her face is a contorted grimace and her hair bizarrely on end. In the left foreground, another female faces the camera. Though she is perhaps unaware of the action behind her, her furrowed brow confirms a physical reaction to the spray. Behind her, a third female covers her mouth and nose with apparent distress.

Juxtaposed with the key figure of the woman in red, these women’s intense reactions to second-hand contact with the spray heighten the viewer’s awareness of the anguish that the woman in red must feel. Though this human suffering is certainly enough to invoke viewers’ empathy, additional signifiers convey more subtle meanings which make the image more powerful within the social context from which it is viewed.

For starters, the girl’s youth, her red summer dress and her purse or book bag evoke a myth of “the girl next door,” a girl we are at once familiar with and unthreatened by. Indeed, the power of this image lies in just how ordinary the girl looks. She does not fit the stereotypical image of a political activist, but rather appears as a bystander caught up in someone else’s conflict. Perhaps she took a wrong turn on her way home from school or work. Even her body position is inoffensive; with one hand on the purse strap and another at her side, she seems surprised, even defenseless.

The subtext of these signifiers – her body language, youth, attire, and gender – make the girl an object of innocence that is instantly relatable and sympathetic. That such a character is subject to such extreme violence without provocation moreover invokes a narrative of victimhood that heightens viewers’ empathy for the girl and provides moral high ground to the protesters.

Contrasting with the main officer’s gas mask and the police squad’s tactical riot control gear, the woman in red’s fate appears further unjustified. The heavily armored police squad does not appear to be restoring order to a hostile protest, but stands like a row of pawns in a chess game. Indeed, the absence of provocateurs from the image’s frame, enriched by the empty green space behind the woman in red, suggests that police are the true aggressors, unconcerned and unfettered by the operational standards of proper use of force.

These polarizing symbols of innocence and abuse of power imbue the image with an iconic presence. Through an emotional and ethical appeal to viewers’ sense of right and wrong, the woman in red successfully mobilizes public opinion. By simply viewing the image, we begin to root for the woman in red and, by default, the protesters themselves.

Photograph by Osman Orsal/Reuters.

Brandon Thomas is an MA student currently living in Istanbul, Turkey. He can be contacted at kingblt@mail.sfsu.edu.