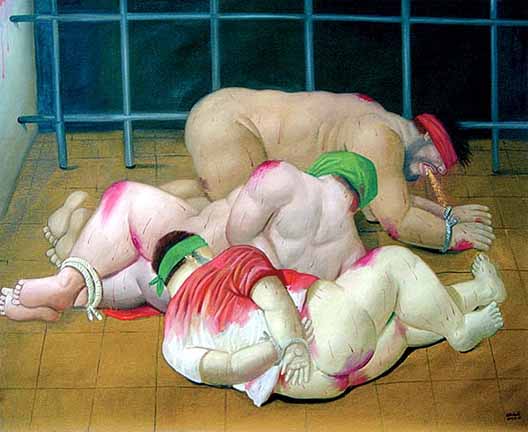

Since my post about Making Nice on a Day of Shame, Michael Mukasey has been confirmed as attorney general. More to the point, yet another attorney general has been confirmed to oversee rather than stop the American institutionalization of torture. Meanwhile, the news has moved on to more important things like the run up to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. Along the way, you may have missed the few stories that appeared about an art exhibit that opened recently at the American University Museum in Washington, DC. The exhibition provides the first complete show of Fernando Botero’s 79 painting and drawings of the torture of Iraqis by American soldiers and private contractors at Abu Ghraib prison. Botero’s work draws on the massy bodies of pre-Columbian art, usually regarding cheery subjects. As Arthur Danto at The Nation remarked on the horrors of Abu Ghraib, “if any artist was to re-enact this theater of cruelty, Botero did not seem cut out for the job.” Others in the know will have shared that thought, until they saw what Botero has done through paintings such as this:

Botero has avoided reproducing those images that have circulated so widely: the cowled, cruciform victim hooked up to wires, or Lynndie England holding a leash or pointing her cocked hands. Instead, he has taken pains to depict scenes that were captured by print journalism. In fact, a Google search will turn up photographs of many of the abuses marked in his exhibition, but that is beside the point. If nothing else, Botero’s paintings provide another attempt to provoke renewed public revulsion, reflection, and debate. There certainly is need for that as the initial photographs are becoming either icons or curiosities. His images also place the scandal into the archive of Western painting while drawing on that tradition to strengthen protest; so it is that the exhibition is compared to works such as Guernica, among others.

One question is whether painting provides a unique form of documentary witness, one characterized by its superior capacity for moral response. Danto, for example, argues that “Botero’s images, by contrast [to the Abu Ghraib photographs], establish a visceral sense of identification with the victims, whose suffering we are compelled to internalize and make vicariously our own. As Botero once remarked: A painter can do things a photographer can’t do, because a painter can make the invisible visible.’ What is invisible is the felt anguish of humiliation, and of pain. Photographs can only show what is visible; what Susan Sontag memorably called the ‘pain of others’ lies outside their reach. But it can be conveyed in painting, as Botero’s Abu Ghraib series reminds us, for the limits of photography are not the limits of art.”

Although the last clause is certainly true, I find this argument to be bizarre, and not only because it contradicts his claim, earlier in the same article, that “it was hard to imagine that paintings by anyone could convey the horrors of Abu Ghraib as well as–much less better than–the photographs themselves.” Of course, once you invoke Sontag, you had better be prepared to contradict yourself. I’m not questioning Danto’s subjective reactions, of course, but I know that he is wrong about mine. And I have to wonder how anyone could think that people were not feeling the pain of others when they reacted with disgust, shame, and outrage as they saw the photographs. Millions of people have reacted that way, which is precisely why the photos made torture a major topic of public debate. One hypothesis is that it may be difficult for those, such as Danto and Sontag, who are steeped in the pictorial traditions of the fine arts to identify with or respond emotionally to photographs. Fortunately, that is not true for the rest of us.

I won’t go on, for surely there is something obscene about turning the depiction of evil into an intramural debate about aesthetics. Whatever the art, there is need to confront the horrors–and the indifference–of our time. Botero has done that, and his artistic medium and style are important forms of witness. He asks, “Is this what 400 years of modern Euro-American civilization has come to? Is the indigenous body still being tortured?”

Look again at the painting. Keep it in mind when administration officials and neocon pundits obfuscate about torture, or when the leading Republican candidates and various editorial cartoonists joke about torture. This holiday weekend let’s not only give thanks for the good life with friends and family, but also renew our resolve to stop state terrorism.

You can see more of the images from the exhibition here and here.

In 2005 I had an epiphany in a gallery at the Tate Modern in London. There I found a series of powerful anti-war paintings (Vietnam and earlier) and a description of a school of artists who had foresworn abstract art in order to “speak” directly to the masses. I was stunned. Where were the artists trying to speak to the American masses? Where was the art objecting to the US invasion of Iraq?

The Iraq war is unusual because the heavy lifting is being done by photographers–despite the constraints placed on them by Bushco; Botero’s exhibition is the first painting I have seen that provides visual wallop although his topic is torture. Too many Americans, alas, when they see photos from Abu Ghraib, conflate “torture” and Muslim terrorist; Torture is somehow okay, patriotic even, because it seems necessary to protect us from Muslim terrorists. Botero’s accomplishment–by showing the effect of pain and torture on those jolly innocent pre-Columbian bodies–is to focus the viewer on the horror of torture. Ones response is visceral, direct–one doesn’t need to be educated in art theory or aesthetics to be horrified. In addition to giving thanks for the good life, renewing our resolve to stop state terrorism, we also need to give thanks for Botero’s vision and willingness to step into the fray.

I wonder how images of torture and the aesthetics of abject art relate to anonymous corpses displayed in Von Hagens’ exhibit, “Body Worlds”? In many ways, these idealized and purified plastinates seem to be the opposite of the visceral bodies and corpses we see in Botero’s paintings and the Abu Ghraib photographs. Why are these plastinates (as opposed to corpses or dead human bodies) dominantly preferred sites/sights of consumption in America when humanitarian activists accuse the “Body Worlds” exhibit of collecting bodies that were tortured or murdered and procured from countries where the distribution on unknown corpses is permitted?

With no detraction from the problems of Abu Ghraib, I wonder if Botero has ever done art work to depict the problems of his own country, Columbia.

I’m surprised that no one here noted the work of Leon Golub!

See, for instance: http://www.flashpointmag.com/golubD.jpg

england is very bad govm & state