Openleft.com has a terrific parody of Bush speaking to the blogosphere; you can see it here. It’s funny, and chilling. Sometimes we need the parody to see what is really being said in public speech. To see how the Bush line is actually going down, look at the photos displayed in a terrific post at the BAG.

In Search of "the people …"

A few weeks back Hariman made the important point that “shrouds” can work in multiple rhetorical registers, masks that can both restrict and enable agency, sometimes at the same time. The focus there was on how individuals can be literally shrouded. But what about something that can be a little more difficult to put our finger on than a living and breathing, flesh and blood person … something like, say, the “American people”?

Yesterday, President Bush spoke before the Greater Cleveland Partnership, a private sector economic development group. Towards the end of the speech he turned his attention to questions of the war, and on the issue of whether or not to withdraw troops he noted that we should not make any decisions until General Petraeus can give his “assessment of the strategy.” And then this: “That’s what the American people expect. They expect for military people to come back and tell us how the military operations are going.” Now clearly the President is not paying attention to the public opinion polls (unlike so many Senators who supported his policy two months ago and now seem to be jumping ship with thoughts of the next election dancing in their heads), but what about the media? How do they frame the “American people” in all of this?

Over at the Bagnews Michael Shaw has made the very important point that many of the representations of the American public from this event seem to mimic Normal Rockwell’s America. And the point is very well taken. BUT, that’s not the only American public being represented, and there might be an important lesson in attending to the array of representations.

Today’s New York Times story features the following photograph (Jason Reed/Reuters):

Now this is clearly not a Norman Rockwell rendition. Notice, importantly, that the president is not speaking to the folks behind him, who have the look of a jury. Largely male and dressed in jackets and ties for the most part, this is not an easy cross section of the “American people.” They are attentive, intense, but clearly not admiring anything. Like a good jury, they seem to be weighing the evidence. But whoever they are, what do they see?

First, we should attend to the fact that the president is speaking with a microphone conspicuously displayed? Why a microphone? Modern technology doesn’t require it anymore, but no doubt it is a prop that creates more of a “feel” of interaction between speaker and audience. Fair enough. But here, note too how it hints at the need for something to amplify the president’s voice, almost as if the mere fact that the president speaks it is not quite enough to get the message across. But what dominates the image is not the president nor the jury behind him, but the much larger and somewhat ominous audience members he is addressing — the American people? — prominently shrouded in dark shadows. We can’t see them, although we can see what they see. The shadows, of course, function in multiple registers. Because indistinct they make it easy for anyone to identify with — white/black, rich/poor, republican/democrat — and certainly much more so than most Americans can identify with the business class individuals in the background. But not just that, the shroud also implies a certain danger (think “death” shroud) — it is dark, foreboding, and (visually, at least) dominating. The image could be from an Ingmar Bergman film. Shrouded here, the public being addressed is empowered and, apparently, powerful – or at least potentially and threateningly so.

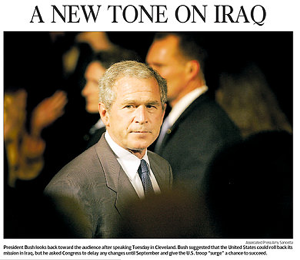

Variations on this photograph have shown up in other places. So, for example, this version from the front page of the Sacremento Bee:

Here, the “jury” has been cropped out. And we see a much more concerned look on the president’s face. The look of concern is reinforced (or framed) by the Secret Service agents prominently displayed behind him. The shrouded public is still there, but now even more ominous. The headline “A New Tone on Iraq” could be referring to the president’s promise to engage in debate over the failures and successes of his Iraq policy, OR it could refer to the changing tone of public attitudes and responses which seem to becoming more and more pronounced with each passing day. But clearly, the public shrouded here is not one to be tarried with, at least not without some attention to the danger lurking in the shadow.

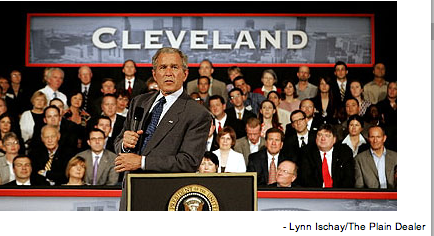

The front page of the Plain Dealer (Lynn Ischay/Plain Dealer) gives us a third option:

It’s not quite the Norman Rockwell shot seen at The Bag or in other places, but it is close. Unlike the picture at The Bag, however, notice that here the president is not blended in with the people behind him. There is a clear distance. And, perhaps more importantly, in contrast to the pictures at the NYT and the Bee, the public being addressed has been visually removed. Now the public is not so much a concern as a ghostly presence that can only be seen in the eyes of the president (and his promise as to “what the American people expect”) or perhaps what now appear to be the somewhat approving eyes of at least of few of his business class jury.

So, we get multiple possibilities. A public who simply gets spoken into existence by the president, and we can believe him or not, or the one he seems to have to address and be accountable to. And the later public is more or less ominous, skeptical and questioning in the NYT image, and downright dangerous in the Sacremento Bee.

How any of this will effect public behavior and response is unclear. But it surely implicates the ways in which we see and are seen as citizens, as “the American people” … and in some measure more powerfully and subtly so than the simple numbers that show up in public opinion polls. After all, seeing is believing …

Iconic Tattoos

Or tattoos of icons, anyway. We already have an image of an Iwo Jima flag raising tattoo on our images page, but this complementary portrait of World War II victory culture just turned up:

Tattoos are emblems of personal identity and of identification with collective symbols. They must mean a lot to some people, but what they mean remains a matter of interpretation, as the discussion here makes clear. The body in this photo obviously was born well after V-J Day, yet another example of how icons can be carried across generations.

Hillary's Feet Get Some Legs

As John posts both here and at BAGnewNotes, I’ll occasionally cite his work there so that folks here can follow it if they wish. A recent post on head, foot, and hand shots of Bill and Hillary can be read here. That story then got picked up by Reuters, which suggests that someone there thought that there might be more general interest. From the comments at BagnewsNotes, its clear that there’s more to feet than meets the eye. In my case, for example, they seem to generate bad metaphors and cliched writing. Comments also demonstrate that there can be a basic split between looking at shot selection and at the content of the photo. The first orientation takes one down the road of media criticism; the second, into the practice of everyday life (e.g., the negotiation between comfort and fashion in selecting shoes, especially for women). Each path can lead back to the other. Both kinds of knowledge are important for participation in democratic politics. And while one may despair that contemporary politics might turn on the nuances of fashion, keep in mind that such attentiveness has been one part of insiders’ knowledge since at least classical Athens, and was made into a virtue in the Roman Republic.

Photography Conference

Locating Photography

Durham University, UK

20-22 September 2007

Following the success of its inaugural conference ‘Thinking Photography – Again’ (July 2005), the Durham Centre for Advanced Photography Studies (www.dur.ac.uk/dcaps) is hosting a second conference in September 2007 entitled ‘Locating Photography’. . . .

‘Locating Photography’ seeks to investigate the relationship between national paradigms and the apparently universal nature of the medium. What is at stake in insisting on or resisting the national paradigm? Why has it been so persistent, and can it continue to provide an adequate framework for understanding the history of the photographic medium in a global, digital age?

Full description, conference program, and registration information are available here.

Kodak Moments from Iraq …

Here is a picture that was posted by the AP on July 2, 2007 (AP/Hadi Mirzban) and found its way onto Yahoo’s “The Week in Photos June 29-July 5,” but thus far it seems to have alluded all the other major news institutions including the New York Times and the Washington Post:

The caption tells the tale: “A 4-year-old Iraqi child cries as older boys stage a mock execution in Baghdad on Monday, July 2. Apparently influenced by ongoing violence in the country, children’s games mimic the war. One of the more popular games is acting out clashes between militias and police.”

I simply don’t know how to react to this. The guns look all too real, as does the pain on the middle child’s face. The smile, however, is perhaps the most troubling of all. It should tell us that this is all a game — not much different, perhaps, from the games of “cowboys and indians” that many in my generation played in the 1950s and early 1960s. But then I recall the smiling faces from Abu Ghraib and the smile of youthful innocence and pure joy seems all of a sudden perverse and obscene. I wonder how we might react if these were contemporary pictures of children from the inner cities of New York or Los Angeles playing “cops” and “gangs.” Perhaps that’s why it didn’t show up in major news outlets.

Main Street, USA … or is it the New American Imaginary?

I am unable to identify a single iconic photograph that represents the naturalization process for those immigrating to the United States, but it is of course not uncommon to find pictures of immigrants being sworn in as citizens at places like Ellis Island, Independence Hall, Monticello, and at court houses across the country in cities large, medium, and small.

And it all makes a great deal of sense, for while no single photo of this process of becoming a citizen may be iconic in itself (i.e., in the way, say, in which Lange’s “Migrant Mother” singularly marks the Great Depression or Eisenstadt’s “Times Square Kiss” singularly marks the end of World War II and the so-call “return to normalcy”), each such image nonetheless locates the ceremony in physical places that are in their own rights icons of the American imaginary. The ceremony of becoming a citizen is thus linked in such photographs directly to a foundational part of the nation’s coming to be — whether historically or at the present moment.

The on-line version of the July 5, 2007 New York Times offered a new twist on all of this, as it reported on a recent surge in applications for citizenship, accompanied by a picture of some 1,000 new citizens celebrating their naturalized status on Disneyland’s “Main Street” after having been sworn in beneath Cinderella’s Castle:

Being sworn in at Independence Hall or Ellis Island or at some other physical place marker of national legitmacy clearly operates in a somewhat romanticized narrative of American citizenship, and so we should be careful about being too critical here. But surely such places are more real, or at least have more of a connection to who and what we are (or want to be) as a people than the pure fantasy of Cinderella’s castle? Or Disney’s version of “Main Street”? Or maybe not.

In any case, the absurdity of the situation must have quickly registered at the Times, because the picture was shortly removed and replaced by a different photograph. The new image, a cropped version of which was actually part of the original on-line story and the full version which was featured above the fold on the front page of the newspaper (see below), shows a close-up of a group of immigrants in the process of being sworn in as citizens:

What is notable about this newer photograph is not only that the physical place has been visually obscured (even the caption relocates the event, emphasizing that the ceremony took place “near” Cinderella’s Castle, not “at it” as in the original), but nearly all sense of individual difference has been muted or removed, as the new citizens appear more or less “uniform,” wearing identical rain ponchos (the one clear exception, of course, is the poncho bearing an image of Mickey Mouse). And I don’t choose the word “uniform” here randomly, for on the front page of the Times this image is paired with and placed beneath an image (that was also part of the original and now no longer available on-line story) of U.S. Marines being sworn in as citizens … and where else, but in Baghdad!

It is hard to know what is going on here. I would be inclined to say that the original on-line story was a parody, something like what we might find at The Onion: “Citizenship Available for an ‘E Ticket Ride’ at Disneyland!” But the NYT is, after all, “the paper of record,” and we would not expect to find satire of this sort here. And of course the front page story seems to play it straight, even though the visual identification between Disneyland and Baghdad could be read in a subtle but cynical register. But then why does the original image of Main Street, Disneyland disappear from the on-line version? The American imaginary is always something of a fiction, to be sure, but here it seems to have transformed into pure fantasy. And one, it would seem, we are all too willing to buy! Perhaps that’s the point. Or maybe not.

Saving Iraq …

I’ve been teaching a class for the past few years called “Visualizing War.” One of the themes of the course addresses the interaction between documentary and photojournalistic representations of war and fictional representations. Many others have noted how fictional representations tend to mimic or repeat more realist representations, but what might be more interesting is the way in which patterns of circulation create a doubling effect so that at some point photojournalistic representations tend to mimic (or perhaps visually “quote”) fictional representations, and thus to draw some of their power from the popular imaginary. My attention was drawn to an interesting recent example by Michael Shaw (BagNewsNotes), who has started a spirited discussion of Scott Nelson’s imagery of U.S. troops in Baquba that appeared in the New York Times on June 25, 2007. The NYT story features the first image below, captioned “An American soldier carrying shoulder-fired grenades paused to wait for orders during an operation on Saturday in Baquba, Iraq”:

There is much that can be said about this image, but what I want to feature for the moment is the way in which the soldier wears his grenades in a manner that suggests that he is something like a “human bomb,” a point vaguely alluded to by the caption. The visual analogy to a “suicide bomber” is hard to avoid here, though there is perhaps an important difference in that the grenades are in full view, for all to see, even though the soldier remains anonymous.

The NYT story ends with a slide show that includes a number of other pictures from the same campaign, but concludes with the image below:

What is especially notable here are the words written on the head band and, importantly, emphasized in the NYT caption: “During the operation, Specialist Paul Goodyear wore a headband bearing a passage from Psalm 91: ‘He that dwelleth in the secret place of the Most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty. I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress: my God, in him will I trust.'” Apparently this Psalm was sewn into the clothing of many U.S. troops during WW II and is worn by many U.S. troops in Iraq. And understandably so given the circumstances. At the same time, however, I can’t help but think about how this image also functions to sacralize an otherwise potentially obscene image (the “human bomb”). And in that context it reminds me ever so much of Private Jackson, the sharpshooter in the movie Saving Private Ryan, who evoked a prayer (Blessed is the Lord) reminiscent of the Old Testament Psalms to guide and sanction his kills, literally to make them sacred. And, of course, his kills were always “clean,” taking place with something like surgical precision, creating no more pain than was necessary to the job at hand, which in WW II was the defeat of evil (with credit to A. Susan Owens for emphasizing the importance of Private Jackson in her essay on “Memory, War and American Identity.”)

My point here is that Scott Nelson’s photography creates a visual narrative of the current War in Iraq that is framed by two images that are reminiscent of a recent and popular fictional narrative of WW II — the “good war.” Reality imitates fiction. And intentional or not, it at least implies a point of connection between the two wars that should be recognizable to many in contemporary U.S. public culture. Or if that last point is too hard of a stretch, at the least there seems to be something of a visual trope here for distinguishing the “good” and “evil” warrior, locating “necessary” and “unavoidable” kills (by sharpshooters then or by the U.S. version of the “human bomber” today) in a sacred register. And it is a trope that we see being worked out in both ficitional and nonfictional contexts, and that should give us some pause as to how the two contexts interact with one another to affect social and public consciousness of things like wars and state sanctioned killing.

Probing the Body Politic

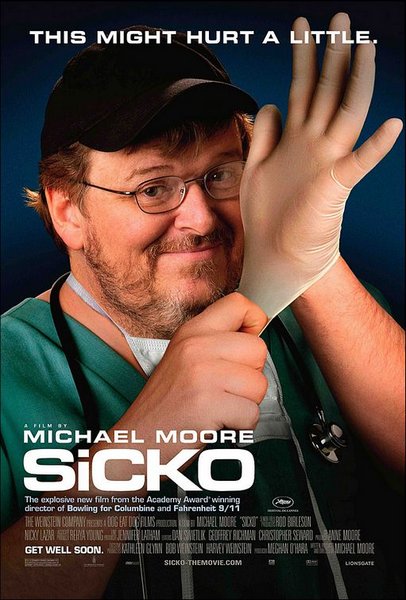

John started a discussion at BagnewsNotes yesterday about how images of hands can be used to signify political traits. Think of the clenched fist of resolve or the democratic wave of the hand. The images of Obama and Clinton are just a tiny part of the archive, however. John and I have begun collecting images of both hands and feet/shoes/boots, which, it turns out, appear in the news media every day. Why, we don’t know, but we’d like to know, which is one reason we’ll be posting examples here from time to time. One indication that these images are means of persuasion is that they are used by savvy designers. Note, for example, this poster for Michael Moore’s new movie:

It’s a visual joke, of course, and one that depends on the audience both recognizing the gloved hand as part of a specific medical practice (getting a vaginal or rectal exam) and understanding that Moore is going to perform the equivalent examination of his subject, the medical insurance complex. And if he does it with the sensitivity we have come to expect of an HMO, they have little basis for complaint. The idea that he’s going to do to them what they do to us depends on the metaphor of the body politic, which is carried by the metonym of the hand. When you think of it, the relationship between the heavy-handed insurance industry and the people is neatly captured by the visible hand and the invisible body it implies.

Boots and Hands

We are working on a new project that focuses attention on the ubiquity of “boots” and “hands” in photojournalism and visual culture more generally. The first installment is part of a post I just did on images of Hillary Clinton and Barrack Obama as a contributing editor at The Bagnews.