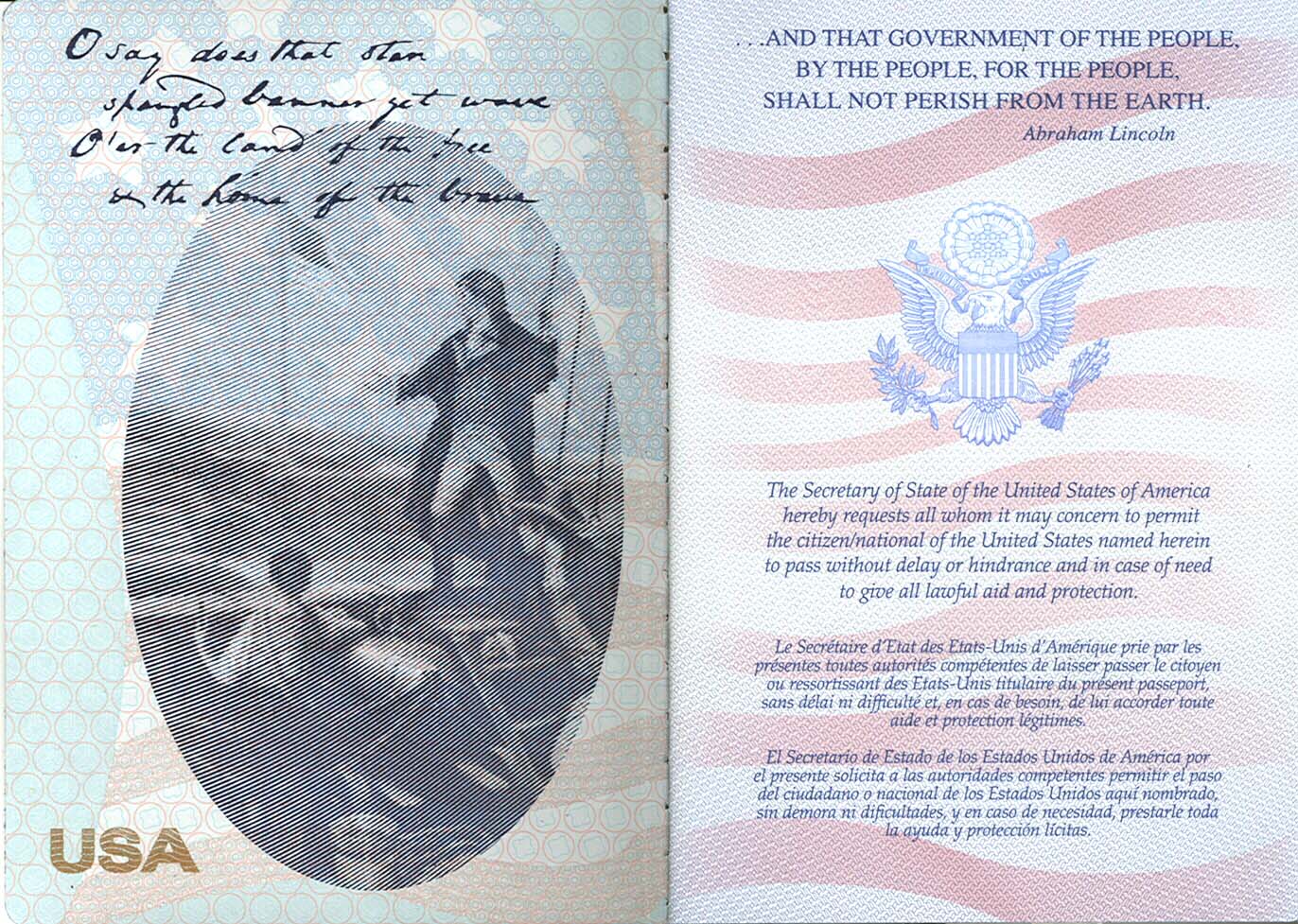

This past week marked the 50th anniversary of the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, one of the signature events of the U.S. Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It was, of course, a chilling moment, as President Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and deployed the 101st Airborne Division to maintain public order and to assure the safety of the now famous “Little Rock Nine.” Photographs of the military occupation of Little Rock abound, but the single image which quickly came to define the moment in the national imaginary, and that has subsequently circulated as the premiere image of the event, is Will Counts’ photograph of Hazel Barnes verbally assaulting Elizabeth Eckrich on a public street.

I was only five years old when the photograph was taken, and have no recollection of the event whatsoever. But the image has been seared in my memory from the moment I first encountered it in 1968 in the wake of the Detroit and Newark “race riots” and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I was in high school at the time and I remember a class discussion in which a number of my classmates agonized over “how all of this could happen.” The next day the teacher brought two photographs to class to fuel the discussion, this one and the image of dogs attacking a man in the street of Birmingham, Alabama. Much of the discussion that day circulated around the image from Birmingham, but this image bothered me much more. Only now do I know why.

The photograph from Birmingham was captioned by the national media as the actions of a racist state run by a racist governor. In the picture from Little Rock, however, the state was missing. There were no guns or dogs. Just citizens. The photograph made me realize for the first time that “politics” had to do with something more than just politicians. I could not understand the relationship between hatred and the hierarchy of racial alterity (indeed, I am quite sure that I did not have anything even approximating the words for it then), but I could see it in the vicious snarl of Hazel Barnes’ mouth and the forward, challenging thrust of her body, as well as in Elizabeth Eckrich’s tightly contained and focused countenance, her mouth closed and thus voiceless, her identity masked by the dark glasses and marked by what Orlando Patterson would later call the slave’s “social death.”

My appreciation for the photograph grew recently while reading Danielle Allen’s Talking With Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education, which provided the words to my somewhat intuitive response to the image. She writes, “… what gives it its immediate aesthetic charge, is that the two etiquettes of citizenship – the one dominance, the other of acquiescence – that were meant to police the boundaries of the public sphere as a ‘whites only’ space have instead become the highly scrutinized subject of the public sphere…. In one quick instant, looking at photos of Elizabeth and Hazel, viewers saw, as we still do too, the skeletal structure of the public sphere, and also its disintegration. Once the citizenship of dominance and acquiescence was made public, citizens in the rest of the country had no choice but to reject or affirm it…. Even today, the photo provokes anxiety in its audience not merely about laws and institutions but more about how ordinary habits relate to citizenship” (5, emphasis added).

The picture continues to be disturbingly poignant, certainly no less so because of the continuing animosities that we find demonstrated in the images we have of the racial divide in post-Katrina New Orleans or, more recently, in Jena, Louisiana. But above and beyond all of that, it also teaches us that photojournalism is about more than just reporting the news, for it functions also as an optic that enables us to see and to be seen as citizens by putting the habits of civic life on display. Indeed, this might be its most important social and political function. Sometimes the words needed to characterize and describe our habits of civic engagement are unavailable or simply do not exist; after all, one of the mechanisms by which power and domination works is to make it very difficult or even impossible to verbalize (and thus lend coherence and legitimacy to) the contrary needs and interests of the subordinate or subaltern classes. What cannot be spoken, nevertheless, can oftentimes be seen, as with the hierarchy of “domination and acquiescence” depicted in the photograph above; and if it can be seen and displayed, then surely it is something we can (and need to) talk about. Photojournalism, in other words, is a vital public art for a democratic public culture that helps us to identify, evaluate, and engage the ordinary habits of citizenship that might otherwise remain unmarked.

UPDATE: For an interesting article and slide show concerning this photograph and the integration of Little Rock see David Margolick’s Through a Lens, Darkly in the October Vanity Fair.