This past week we honored America’s veterans, but except for a few conventional news stories and ritualistic photo ops the day passed with little notice or fanfare, eclipsed in the national consciousness by trying to figure out who President-elect Obama will appoint in his new administration and political wrangling over how to address the so-called “financial crisis.” And what has been missed (or is it repressed?) in all of this has been the 150,000 U.S. troops who continue to occupy Iraq (and who are likely to continue to occupy Iraq until at least 2011); the 278 U.S. military deaths and 1,500 + U.S. military casualties that have occurred in Iraq since January of 2008; or the astonishing admission by the Veteran Administration that on average a staggering 18 veterans commit suicide everyday.

It is against this background that I was stuck by this AP photograph that showed up in a number of on-line newspaper slide shows this past weekend.

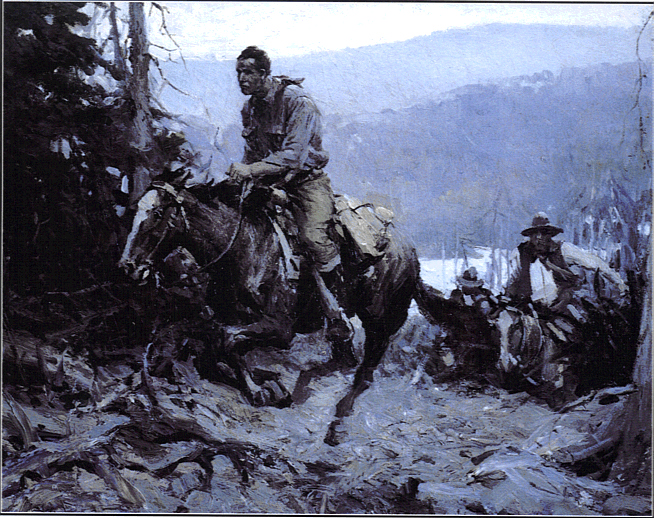

The image is of a young girl as she “looks at a life-size painting of men from the Columbus-based Lima Company, 3rd Battalion, 25th Marine Regiment, 4th Marine Division” that is part of the Lima Company Memorial at the Cincinnati Museum Center. Lima Company suffered some of the heaviest casualties of any unit fought in Operation Iraqi Freedom, including the death of 22 brave marines in a very short period of time in 2005. There is no question but that their service and sacrifice needs to be sanctified in public memory and yet there is something altogether unsettling about this photograph. Part of this (dis)ease is no doubt a recognition of how an innocent child—and a young girl at that—serves as the cipher for orienting the model citizen towards the nation-state as a gendered and infantilized spectator.

Children, we are told, “should be seen and not heard.” Notice here how the young girl silently directs the national gaze upon the marines even as she holds their attention. The colors of her hair, sweatshirt, and pants coordinate perfectly with the red, white, and blue of the flag that she holds and thus cast her as the metonymic (and fetishistic) embodiment of the nation-state. Her shadow marks the corporeal distance of the passive spectator from the painting no less than the candles, boots, and photographs that frame it. There can thus be no mistaking that the young girl is a passive spectator clearly separated from the scene in the painting—seeing and not speaking or acting. And so, we must wonder, is she a child citizen or the citizen-as-child?

There is no final answer to this question, of course, but the smiling and approving gaze of the marines seems to suggest a paternal protectiveness of the child/citizen/flag that resonates with normative assumptions of the public as an innocent and passive child and all of that is troubling for those who might imagine a vibrant democratic public culture. But what if the child was not in the photograph? How else then might we understand the painting as part of a public memorial?

This life size canvas, it turns out, is one of eight panels portraying all 22 marines from Lima Company painted by Anita Miller, a liturgical artist motivated “to paint images that open the viewer’s eyes to the beauty of the world.” In each of these eight panels we have portraits of two or three of the deceased marines and in each instance we are presented with a smiling and caring countenance. And there can be no doubt that the images offer comfort to those who knew and loved these men as friends and family members within the contours of private life. But when cast as a war memorial the appeal to the spiritual beauty of the individuals doing the fighting diverts attention from the sheer ugliness that is combat regardless of the cause. War’s “beauty”—if that is the right word—is terrible, and that is a lesson that we forget at our peril.

And so, once again back to the photograph and the young child who gazes upon the scene with what we can only imagine is beatific awe and admiration. And the question here must be, is this the best way to transport the civic virtues of sacrifice and service from one generation to the next? I am not so Pollyanna as to believe that wars will never be needed—though hope springs eternal— but I never want my children to think of war as “part of the beauty of the world” or that those who do the fighting do so with a “smile” upon their face. We owe the men of Lima Company more than that.

Photo Credit: Ernest Coleman, AP Photo/The Enquirer