By guest correspondent Rachel Rigdon

Despite the Great Recession and the escalating rates of both poverty and economic inequality within the United States, finding images of poor Americans within the news often feels like a process of excavation. There is a curious deficit of photographs of the 44 million Americans living in poverty, and in lieu of using photographs, many articles on welfare or economic inequality feature graphs and charts. One result in a dominant framing of poverty as a purely economic category rather than as a condition of life.

One of the few photos that I have found accompanying an article about poverty is this image from Time Magazine’s blog. Taken at a soup kitchen in Detroit, the focus is primarily on the family sitting at the table in the bottom right of the frame. The background subjects are blurred, creating a sense of a rushed, noisy environment surrounding the family, and yet the large open space of the maroon table offers a small sense of calm. But the photograph also is off-center, tilted, and unfocused, and thus it captures the incongruity of the private, domestic ritual of a family dinner occurring in a public setting. By positioning the viewer slightly above the edge of the table as if about to take a seat, we are invited to imagine poverty as the backdrop of an otherwise normal life.

In response to the limited numbers of photographs of U.S. poverty within the media, a group of photojournalists joined together to create AmericanPoverty.org as a shared space to publicly document the lives of the poor. The website automatically opens with a short slideshow of photographs accompanied by dramatic music and text. Opening with the phrase: “For decades American poverty has been invisible,” it then quickly cycles through several images, mostly of children and families, before pausing on an image of a young, white girl in front of a trailer house. Here text emerges, saying, “It’s not invisible anymore.” The photojournalists’ goal is that by rendering visible what has been invisible, viewers of the photographs will demand social change.

This appeal to potential advocates is present in the choice of photographs for use in the slideshow. All of the photos are of sympathetic subjects such as children and families. Many of the images feature the subject, usually a child, looking directly at the camera as if asking the viewer to see them. These subjects demand a response from the viewer—by virtue of both their embodiment of the large-scale realities of poverty and economic inequality and their identity as equal citizens living unequally.

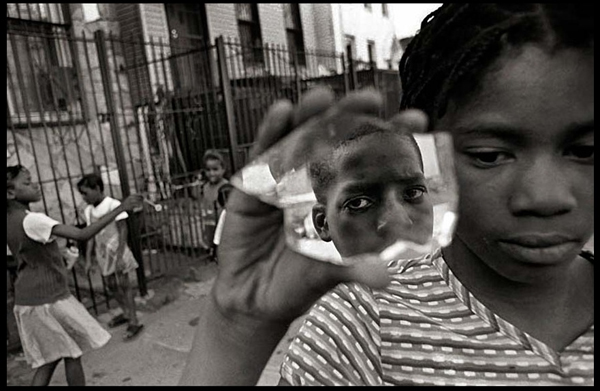

One of the more engaging photographs within the video is this one of several children playing in New York. The primary focus of the photograph is the reflection of the boy in the middle. His face is serious, his eyes intently focused on the reflective surface before him. This use of the mirror mimics the active work of photography by providing an image of a moment that seems to be of reality, while also announcing the existence of the apparatus that can only provide a partial and fractured glance at its subject. The camera’s position is aligned with the boy’s, making what we see within the photograph representative of his viewpoint. The photograph reveals a moment of American life, and our own understanding of it, to be as fractured and incomplete as the boy’s reflection.

In contrast to the boy’s resistant gaze, the girl who holds the mirror is downcast. In the literal sense, she is showing us (the boy, the photographer?) something: a piece of broken mirror. She is also revealing the sad resolve of the boy’s reflection, the proof of poverty’s withering effect on the soul, and the loss of a happier childhood being modeled by the three children playing behind her. The children in the background are playing with bubbles next to a tall, metal fence. The combination of the fragility of the small children and the bubbles with the harshness of the broken mirror and the prison-like connotation of the gate results in a sense of unease. The happier moment playing out in the background seems destined to disappear as the harsher realities of life reveal themselves in ever sharper relief.

Both of these images point to the ways in which poverty transforms the daily activities of life into moments that are both familiar and foreign. They produce a sense of dissonance through the combination of familiar practices with the realities of need. The ritual family dinner becomes displaced by the family trip to the food kitchen; playtime involves bubbles and broken pieces of an automotive mirror. These photographs not only attempt to render visible what is invisible; they also try to render legible the normalcy of poverty. By illustrating scenes of daily, familial life, viewers are encouraged to both identify with their familiarity and be horrified by the inequality they unveil.

Unlike the graphs and diagrams that so often stand in for the visual experience of American poverty, these photographs draw upon powerful values about family life, the protection of children, and our shared sense of horror at their violation. They also challenge the ideology of American exceptionalism and the promise of liberal democracy to provide a high quality of life to all of its citizens. And perhaps this is the real reason that these images and these people remain invisible—they are American yet they trouble our sense of just what that means.

Photographs by Spencer Platt/Getty Images and Brenda Ann Kenneally.

Rachel Rigdon is a graduate student in the program in Rhetoric and Public Culture, Department of Communication Studies, Northwestern University. She can be contacted at rigdon@u.northwestern.edu.

7 Comments