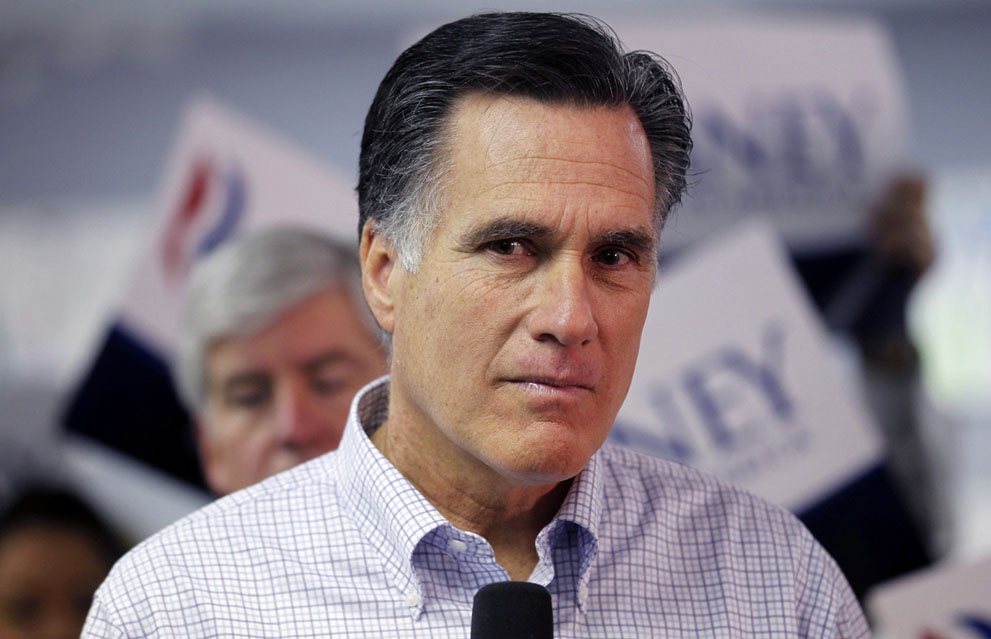

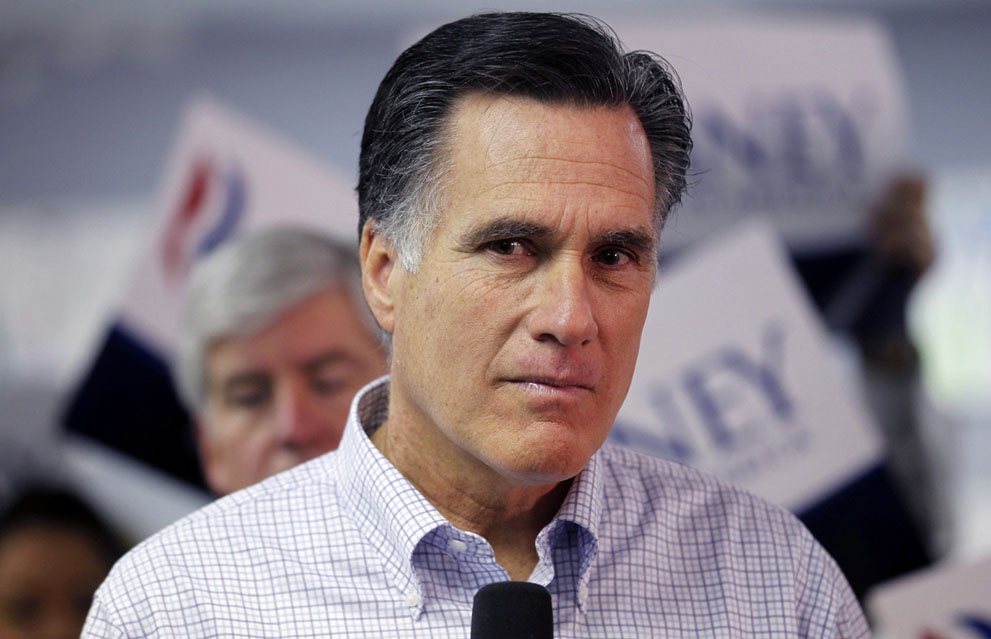

You may not have noticed, but part of the current renaissance of photojournalism is the continuing development of the slide shows offered by online newspapers and magazines. Before waxing nostalgic about the glory days of Life and Look, spend some time at the Boston Globe‘s The Big Picture, the Atlantic‘s In Focus, and similar sites. You will see that the editors are doing more than slapping together the news of the day or putting up human interest eye candy. I won’t say they are immune to those tendencies, but most of the time they are going one better to help create a richer and more visually literate public culture. And speaking of culture, when Alan Taylor at In Focus put together a set of photos under that label in response to reader requests, he included this portrait of Mitt Romney. Taylor will have had many requests, but he had a stroke of brilliance in selecting this subject for a show on culture and this photo for what would otherwise be the most conventional of images: the candidate profile.

Taylor reports that he looked for a photo “that let you see him [Romney] as more of a person, less a politician.” So he was trying to get us to see through the usual framing of the political candidate–you might say, to actually see him as he is, rather than to simply see the stock character in the standard pose. Although Romney hasn’t stepped out of role–he’s still carefully groomed, tactically controlled, precisely calculative, and even a bit wary–the portrait creates a sense of something like intimacy. Indeed, he seems exposed rather than scripted, and despite the fact that his shirt, haircut, and tan are thoroughly conventional, he is inescapably a single, specific person. This is the image of someone who has a history, personality, and mortality all his own. Being cast into the glare of the public stage clearly frames, envelopes, and may consume him, but he is who he is nonetheless.

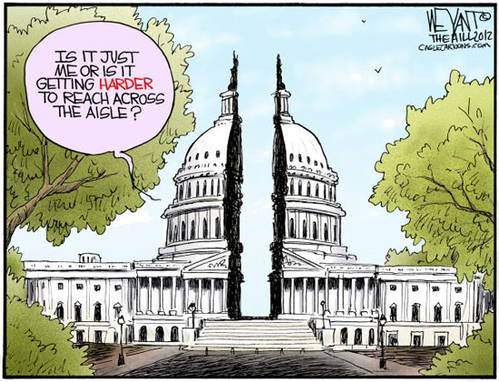

But is this culture? Aren’t we told that culture is art and artists and other things that, whatever else they might be, are more unusual, unconventional, and even otherworldly than a mainstream presidential candidate. Something like this, for example:

This photo from a Comic Con event (which would draw fantasy, sci-fi, and gaming enthusiasts) would seem to fit the bill for “culture.” A woman has costumed herself as a character from the “Portal” computer game, and whatever she is, she is not yet another politician. No wonder that she was the lead image for the slide show: her ghostly hair and skin, space-age clothing, and cyborg eyes create an uncanny effect: she is both human and not human, image and reality, organic material and living artifact. In other words, the conjunction of 21st century folk art and good photojournalism has given us a different kind of exposure: we can see how the human being could become alien to itself. That is, we can imagine how human and alien are in fact kin, like image and reality, perhaps. Nor does this recognition scene have to be set in a fantasy world. Right here and how you can look at this alien thing and realize that she is human. And thus that what is human is from another vantage also alien.

Just like the first image. The best reason they both belong under the “culture” label is that they are the same image. Each one reveals how human being depends on self-representation that is inherently uncanny, were we but to step back and notice. So it is that I want to push back a bit against the caption provided at In Focus, for the verbal text puts a familiar face on what otherwise can be a troubling image. Romney is a real person, of course, so this is not a question about veracity. But it is reassuring to be told that someone who is spending hundreds of millions of dollars to present his image to hundreds of millions of people is in fact still an individual human being, one of us. I think that deep artistry of the photography is this: at the same time that it is presenting the individual person, it also is showing us how much we don’t know about Mitt Romney, and how much we rely on a very few stock features to feel comfortable with him, and how much the public’s relationship with him will remain a relationship with a skillfully crafted image.

If you don’t buy it, reverse the order of looking at the images; then look carefully at her to see how she is in fact a specific individual, and then do the same amount of work to see him as an artful composition, as someone acting like a person. This is not done to claim that Romney or any politician is somehow more phoney and less substantial than the rest of us. Degrees of performance still exist, but my point is precisely that he and you and I could not do otherwise than to exist as both actor and character, familiar and strange, human and alien.

So it is that he perfectly mirrors her, and she perfectly mirrors you.

Photographs by Gerald Herbert/Associated Press and Leon Neal/AFP-Getty Images.

0 Comments