There is no way that press coverage of the Mississippi river flooding can match the damage, discomfort, and discouragement that is spreading across the flood plain. Maybe the coverage really doesn’t matter, but if it does, people are getting too little of it. Nor is this surprising. Big news from the Middle East continues to overshadow a story driven by the weather. The news is drawn to dramatic events, while the flood has been spreading slowly. Tragedies are supposed to be monumental, but the flood is about sandbags and soggy carpets.

You might say that this photograph says it all, precisely because it says so little. A woman is carrying clothing out of a flooded house. She is wading through the kitchen, which is standing in a couple inches of water. The kitchen looks like many other kitchens across America and the world, right down to the magnetic decorations on the fridge. The one difference is the water, which is not too deep but thick with mud and getting under everything. Her expression is just right: this is an unexpected, unwanted chore, and one requiring concentration so that you don’t make it worse, but what can you do except wade through it? Why waste time complaining? Or making a big deal about it in the news?

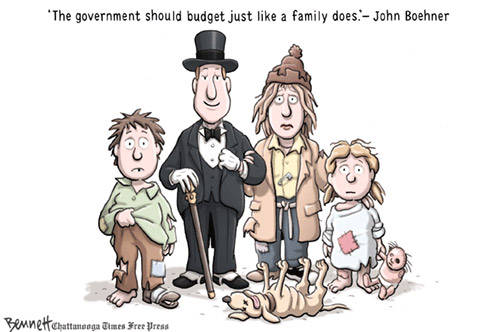

The house has not burned to the ground, been devoured by an earthquake, or shattered by artillery shells; it’s just wet. So it is that floods usually fall short of other disasters in terms of visual interest. You can only look at so many photos of a boat being piloted down the street of a small town. But something is being revealed, nonetheless. The problem is not the nature of the disaster, but of a media system that is not suited to capturing conditions of general deprivation. The news is drawn to emergencies, and to making emergency claims, but not to understanding how large groups of people may be on the edge of despair or at least having to get by with far less support than others take for granted. Consider, for example, how the health care debate was hijacked by images of Tea Party protests, allowing millions of people to be shorted and billions of dollars squandered for want of being able or willing to depict systemic problems on behalf of the general welfare. Also lost along the way was an appreciation for the fragility of human life and the social systems that we erect to protect ourselves from the forces of nature.

Another woman, another room of the house, another natural disaster. This bedroom was exposed to the elements by a tornado that blew through Alabama not long ago. (Remember?) Once again, you see a demonstration of the coping skills that are so essential to everyday life. The walls have been torn away, but what can you do except sort out the possessions that remain?

What strikes me the most about the scene is that the walls were so close to the bed. We’ve all been in small bedrooms, but how often do we then feel that we are just on the other side of the outside? Here we can see that, large or small, a house is but a thin shell between inside and outside, between the forces of nature in all their violent capriciousness and the shelter, security, warmth, and everything else we hold dear when in our own space.

Whether flooded or torn asunder or still intact, a house is a fragile thing. More generally, housing has proved to be a fragile part of the national economy, one that, if poorly managed, can come crashing down to spread harm far and wide. When deregulation allowed the housing market to be flooded with financial malfeasance, disaster struck, and ordinary people who had done no wrong were left to pick up the pieces.

We live in shells. When they are well built and protected, we forget how fragile they are. When disaster strikes, the thin barrier between ordinary life and catastrophe is exposed. What remains to be seen is whether anyone else will notice or care. And care not just about this house or that one, this town or that one, but enough to rebuild a society with the protections and support that ordinary people deserve and need. It’s called government, by the way.

Photographs by Scott Olson/Getty Images and Butch Dill/Associated Press.