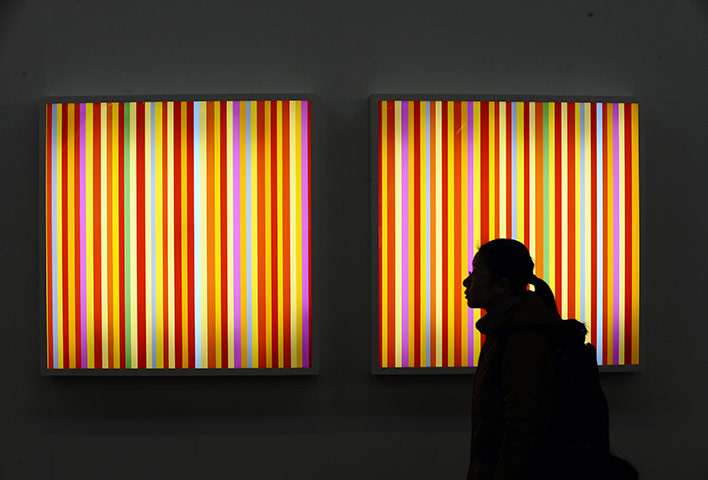

Photography’s subjects include the other visual arts along with their institutions such as museums, theaters, galleries, shows, festivals, and auctions, and their modes of spectatorship such as gallery tours or 3-D movie audiences. So it is that occasionally the daily slide shows include images such as this one.

A woman is walking past an artwork at the 2011 Armory show in New York. It is significant that she is shown in silhouette, that the photograph’s caption didn’t include the name of the artwork or artist, and that both spectator and artwork are framed in black. Art and spectator are unified by a shared darkness, which also places them in a figure-ground relationship. She is tied to the artwork even though not looking at it (she is walking by as if it weren’t even there to be seen), and it becomes the vehicle for revealing her presence (as if it had been designed for that purpose). Neither inference is true, yet that is irrelevant to the photograph’s artistic effect as it is viewed by another, unseen spectator: you.

Way back in the twentieth century, it was easy to speak of the human person ensnared in structures of alienation, and to believe that the art could expose that alienation. One could read this image in that way, but, well, the colored panels are just too bright, and the human form is not so much trapped as simply passing by. By featuring both the jawline and the tightly bound ponytail, the silhouette has a decidedly anthropological cast. She seems to be almost primitively human, as if part of one of those 19th (and 20th) century “ascent of man” pictures that were a centerpiece of evolutionary anthropology during its racist and sexist heyday. But isn’t she going in the wrong direction? Yes, and that is one reason we can assume that the old hierarchies no longer apply. But what is going on?

The answer lies in the artwork behind her. She is carrying her culture with her while passing through the historical corridor of modern art, while the art seems both more vibrant and the more enduring structure. Its form imitates the bar code or other modes of systematic information display as they are designed for machine processing. She is not so much alienated by that information as simply different from it; not so much alienated from the rectilinear code as the life form that is symbiotically related to it. She is a human being while it is a human design, yet she is relatively primitive as it no longer needs her input while being more directly transferable across the domain of information systems. (Consider which one is easier to reproduce.) As one of its tertiary functions, however, it provides the lighted background so that she can remain visible.

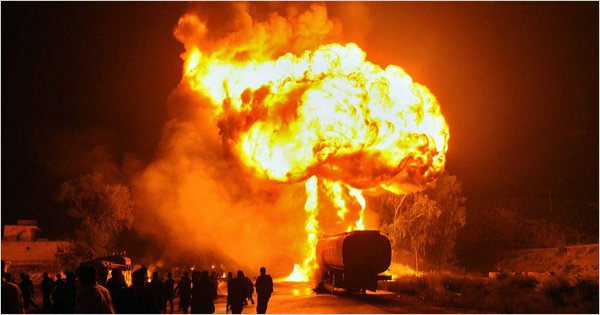

And remaining visible may be a gift worth having. This image from the Shenyang stock market was taken far away from the Armory show, yet it uses a similar artistic repertoire. The human figure is caught, albeit only in silhouette, as it is passing across a lighted data array. The gauzy screen that is partially visible provides a nice artistic touch, suggesting a medium in both the technological and spiritual senses of the term. Again, however, the mood can’t be fraught with angst: true, this time the colored columns are somewhat intimidating, as if in a dream that is going bad (the blurry numbers tower above him while an alarming red band cuts across the screen at waist level), nonetheless, he is a happy fellow, smiling brightly as it hurries along. As he is going in the same direction as the woman above, we might wonder what is there, off in the back lot of the march of progress?

More to the point, however, we might ask what value there is in highlighting the human form in a very modern world. Both the stock exchange and the Armory show are marketplaces, and the human figure thus acquires not only aesthetic but also economic significance. Photojournalism, which seems resolutely dedicated to realistic documentation of people and places, also can provide a different artistic platform for thinking about larger questions of how humans can inhabit the markets and other impersonal information systems that constitute modern life.

Artworks in their own right, photographs such as these can raise good questions about the human image, and, with that, about our place in a strange world of our own making.

Photographs by Timothy A. Clary/AFP-Getty Images and Tian Weitao/Xinhua-ZUMAPRESS.com.