Usually I avoid rubbing your face in it, but not today. This image, which has been sitting on my desktop for a few months, is offered out of anger, grief, and extreme frustration with the press, the public, and the Obama administration–and most of all with the public.

The photograph records a badly maimed soldier being delivered to a military hospital in Kandahar. Think of how many times you have read about IEDs and about wounds suffered from IED explosions. Did you ever imagine anything like this? Think of all the photographs you’ve seen of soldiers standing guard, walking on patrol, talking with villagers, or deploying for another mission. Did you ever consider how those photos were being used instead of images like this one?

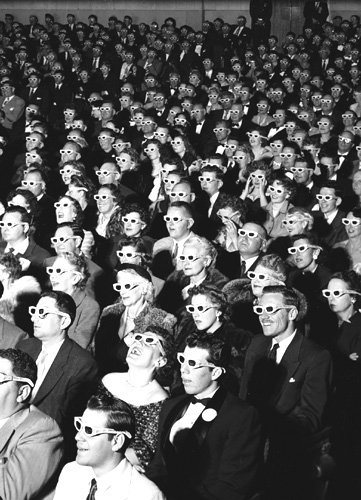

And while we’re asking questions, did you notice, when looking at the photograph above, how absolutely routine this event is to the medical personnel? Only the soldier jogging out the door looks a bit concerned, and he may be steeling himself against what he knows he is going to see up close. Everyone else, including the stretcher bearer, has the postures–that is, the attitudes–of complete habituation. The guy on the right could be waiting to take a number at the social security office. Something horrific, catastrophic, and uniquely terrible has happened to the soldier on the stretcher, but to everybody else it’s something they’ve seen a thousand times.

If the war in Afghanistan were vital to national security, perhaps this sacrifice would be worth it. If you have to fight, you want your military to have the experience and other capabilities necessary to handle catastrophic injuries efficiently. But we know that national security is not on the line in Afghanistan.

We do know that, don’t we? Two stories intersect today to underscore my frustration: First, press analysis of the WikiLeaks archive of 391,832 documents is exposing greater than admitted death tolls, abuses by US contractors, and brutality by other US allies, as well as US knowledge or and lying about this information. Second, New York Times photographer Joao Silva was badly injured by a land mine in Afghanistan. Leg wounds, and others as well.

One reason I am so angry and frustrated is that there really should be no need for the Wikileak documents, or for brave photojournalists to continue to take risks to inform the public. I want to take nothing away from those who released the documents, or from Silva, whose work I have posted here with deep admiration and respect. The truth of the matter, however, is that the public has had plenty of information for many years about the sacrifice of our troops and our treasure in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Likewise, the government has known even more of the costs, and has not yet–in all this time, and across two administrations–been able to provide a single, legitimate, valid rationale for continuing the war. (For the record, I think the original invasion of Afghanistan was justified, but that now has no bearing on the current operations. And I appreciate that public opinion polls state that a majority of Americans oppose the war, but that level of opposition obviously is not enough.)

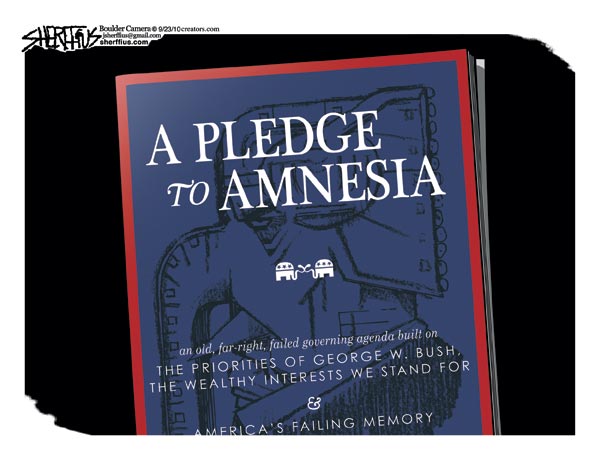

I think the basic problem is that people, at least collectively, decide to know. It is not the case that we know and then act. We decide when we will know, and then we are more likely to act. You can have the truth staring you in the face, but it doesn’t matter until you decide to suspend all the habits of amnesia, distraction, rationalization, and denial that are otherwise in place and reproduced continuously. Once we decide, we can look back and see that there was plenty of information there all along. But we have to make that decision.

The question remains, what will it take to get enough people to decide to know that our war in Afghanistan is futile? Sometimes, a photograph will make the difference. But how many photographers and soldiers have to be used up until that day arrives?

Photograph by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

9 Comments