Well, not any old day, actually, but Game Day:

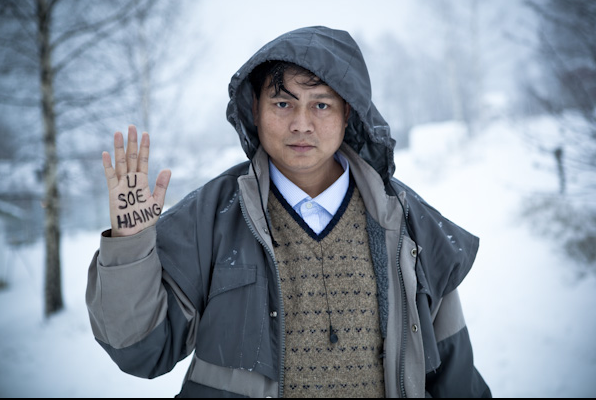

And it’s not primitive, either: those nails are a product of the machine age, thank you very much, as is the plastic material used to form the mask. But it is a mask, and he is masked, painted, draped, and otherwise transformed externally and internally for ritualized combat. That combat has to be imagined between individual warriors, as there is no point in one man trying to frighten a platoon or a plane. The attempt to terrify is more intimate still, for he bares his teeth as if to rip your throat out. The fact that they are painted the same colors as the mask adds to the threat, for it says that he has been made into a single being for a single purpose. Man and mask have become one thing–and it is a thing, as the eyes, window of the soul, are vacant.

If you have any doubt of his now inhuman will to power, look at the nails: he has cannily challenged his adversary by mortifying himself first: what can be done to terrify him, when he has already mutilated his own image? But who is he, anyway, now that he has fused his identity completely with his team, his tribe? Although merely a very modern Miami Dolphins fan enjoying the carnival culture of a live football game, he is nonetheless channeling the artistry, psychology, and mythic resonance associated with primitive societies–at least as they are used to supplement or escape (temporarily) the dominant designs of modern life.

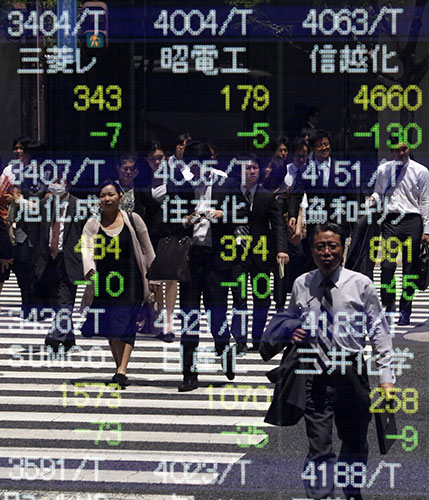

Designs such as this, for example:

Although wearing wrinkled corduroy slacks, this museum visitor is neatly turned out for public viewing; you might call it uptown casual, and you can find it any day of the week in the museums and similar venues for Art and Culture. The basic black jacket, corresponding gray slacks and gray-white hair with just a hint of muted color in the scarf for accent, along with the sheer geometric surfaces devoid of ornamentation–these are standard features of modern design (and, since men started wearing black in the 19th century, of modernity itself). If you aren’t sure, just look at the painting, where the design principles have been perfected.

As with the first photograph, the image is striking because of the homology that ties person to thing. Just as colors joined mask, teeth, and tribe, now color joins spectator, painting, and modern design. And where the first image was carnivalesque, this one is gently humorous. What is there to see in that black void? Will peering intently discover anything in black but black? Isn’t it amusing that person and artwork seemed to be doubles: that a black surface mirrors an actual person?

It takes only one more step for the joke to turn into something else: perhaps the painting does mirror the person, who may be largely a void after all, and also not much more accessible to the rest of us who can only see the individual from behind, as it were, and as a social type. And is art imitating life, or is life being made over according to an aesthetic that is abstract, impersonal, dehumanizing–the expression not of the individual person but of mechanization? And what is the photograph but a witness to Nietzsche’s admonition that “When you stare into an abyss, the abyss also stares into you?” Perhaps this photograph is a study not only in modern design, but also in a distinctively modern form of terror.

But not the worst terror. Here we have a third thing: simultaneously primitive and modern, machined and animal-like, horrifically Orwellian yet an actually existing scene from the present. The workers in their Hazmat suits are cleaning up a toxic sludge spill that inundated a village in Devecser, Hungary. The costumes are awful, terrifying, and yet not intended to scare anyone. Even so, there is something terrifying about the suits, not least because the workers seem so completely habituated to them–as though this was just another day on the job.

And that’s one more thing all three images have in common: each is a photograph taken from a relatively special event rather than a typical day’s activity–and yet each of them suggests that something both terrifying and deeply continuous is in fact present. Blood lust is always there; it’s just a question of how it is sublimated. The abyss is always there, along with the grinding uniformity of modernization; it’s just a question of how to live well anyway. The catastrophes that result from industrialization, environmental exploitation, and the continual assault on the commons are becoming woven into the fabric of everyday life in far too many places; the question remains of who is going to do what about it.

So take a look at each one and ask yourself which world you want to live in. You can stare as long as you want to.

Photographs by Allen Eyestone/The Palm Beach Post; DPA; Bernadett Szabo/Reuters. The Nietzsche quote is my translation of the passage from Beyond Good and Evil, part IV, section 146 (1886). On the role of black in modern dress, see Men in Black by John Harvey.

0 Comments