H. Rap Brown once famously remarked that “violence is as American as cherry pie.” Brown was challenging dominant myths, not least the idea of America’s providential exception from the dark side of history. Now that America has become a major exporter of violence, Brown’s statement may seem antique. Myths die hard, however, and it remains difficult to say who might make people stop and think about the production of violence today. One place to look is an installation by Yoko Ono in Berlin.

This photograph captures the artist posing behind her artwork entitled “A Hole.” Perhaps the work need not appear to be a bullet hole, but it certainly becomes that when backed by the blood and black silhouette of her head. It’s easy to fault Ono for putting herself in the front (even when in the back) of her art–Is at all about her?–but I think that is mistaken. She and the photographer have created a moment of near-perfect performance, one that captures the deadly allure of the aestheticized violence in its mass market forms of detective fiction, Noir and action films, and even high fashion.

The image is a set of contrasts (of course): shimmering surface and dark depth, centrifugal dispersion across a plane and the concentrated energy of the human figure, obliteration and the human face, a circle of nothingness where a person should be. Add to this the tension between the formal elegance of the composition and the shattering force at its center, and violence seems to become an aesthetic achievement. If so, one might recall Walter Benjamin’s prophetic observation that humankind’s “self-alienation has reached the point where it can experience its own annihilation as a supreme aesthetic pleasure.” That may be, but one also could consider that the photo is highlighting some of the design elements of how that already has happened, not here, but elsewhere: in the movie theater, for example, or the nightly news.

It takes nothing away from the artist to note that the art can reveal only some of the truth of a complex reality. So it is that the artistry of the image ought to be balanced by another photograph, one that may be thought of as looking at the same thing from the other side.

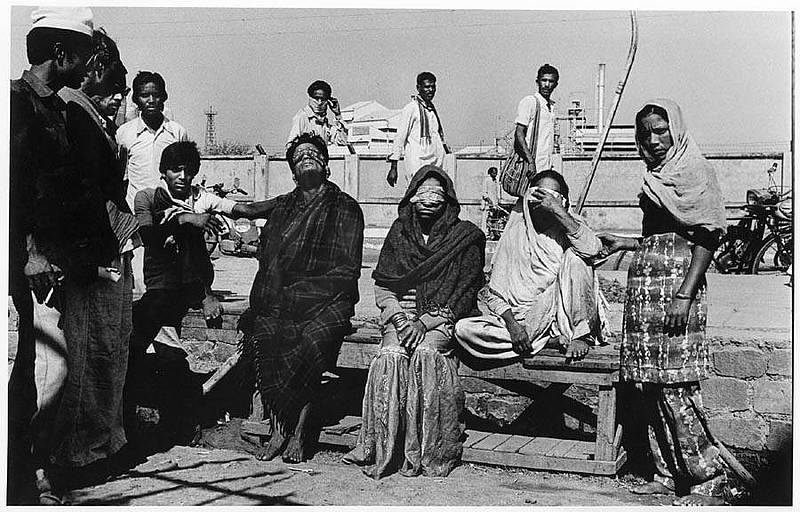

This image is more conventional than the photograph from Berlin but an artful study in violence nonetheless. Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front leader Mohammed Yasin Malik stands in front of a crowd of supporters in Srinagar, India. There are no bullet holes or other overt signs of violence here, yet the scene is all about violence and the potential for violence. The liberation movement represents one side in a long-standing and often violent conflict over Kashmir; the crowd is protesting brutal crowd control measures by Indian government forces that have included killings; the crowd itself is capable of becoming a mob (such is one source of crowd power and its frequent definition by the state); and the leader could both unleash violence by the crowd or revolutionary fighters and be himself a target of assassination.

Here Politics mediates violence just as Art did above. In each case actual violence is off stage, but its presence can be felt powerfully. In the first photo, the violence is completely artificial but visible; in the second, it is implicit but leads directly to actual deaths. Both are moments of performance, with the artist remaining hidden and the politician exposed to public scrutiny: and yet both are enigmatic, as you don’t know the artist’s opinions on the subject, while the political leader looks by turns hard, worn, calculating, concerned, and both a man of the people and yet set apart and isolated by his role. In the first image, the scene is nowhere and anywhere there is a cinema; in the second, the urban masses of the Global South are paired with a figure who could be stepping out of Shakespeare. Put the two photographs together, and Malik becomes the figure behind the hole made by the assassin’s bullet.

In the first image, the spectator could be the assassin; in the second, it could be the state. It remains unclear whether that is much of a difference.

Photographs by Hannibal Hanschke/EPA and Mukhtar Khan/Associated Press.

Credit: John Sherffius, Boulder Daily Camera.

Credit: John Sherffius, Boulder Daily Camera.