No one talks about building character when covering Olympic level gymnastics. If anything, the intensive training regimens that start soon after infancy are likely to stunt development of everything not necessary for athletic achievement. Denial is the order of the day, however, so the coverage is very soft focus when dealing with the production side of modern sport. What we do see are the intended results:

Unbelievable, isn’t it? Astonishing, amazing, incredible–and she’s barely past childhood. Nor is this a trick of the camera: look at her musculature, and the sure control of her limbs, and the arch of the neck as she keeps her eyes focused on the landing. She is flying through the air as the rest of us will never do, a moment of perfect freedom achieved only through extreme discipline.

The photograph presents a double image that supplies the soft focus background for her achievement. The athlete of the moment performs against an image of her type. Life and art are perfectly coordinated: the larger image in the background provides a sense of aesthetic tradition that frames and guides the live performance. The background image could be the performer herself at a slightly younger age, already radiating the innocence of a young girl perfectly composed, or the sport as it represents both excellence and aspiration. The athlete in the foreground reveals how innocence becomes transformed by the drive train of competition. She is entrained with the standard against which she will be measured, and yet upside down–everything she might have aspired to do, but at a higher level of difficulty.

Nor is she merely a study in form; the image is explosive, as if she has been launched from some modern catapult. Surely this is one sign of the incredible technological power of modern civilization–not least its capacity for complete optimization of human skill and energy toward a specific, highly defined task.

That relationship between the individual and social order might well be the subject of this photograph:

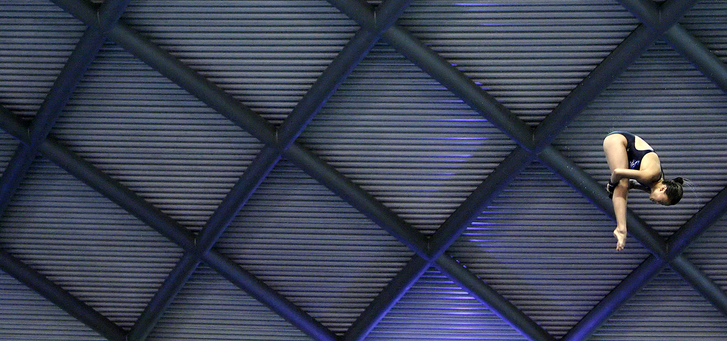

Like the photo above, this image features a world-class athlete at a warm-up event for the summer Olympics. The diver also is entrained with her background–each are studies in rectilinear form. Black and white or black and grey, squares become diamonds as they are pointed toward the water below. Oddly, she is placed off to the side, as if the building were the subject of interest; as if she were but an ornament hanging there to complete the architect’s design. The immensity of the horizontal space may imply an equally deep vertical drop, but the effect is not one of action or risk but rather of order, of individual and structure in perfect equipoise.

The images differ in their sense of time. The first implies a world of artistic continuity via ascending achievements. The girl of the past will be replaced by the girl of the present, who one day will be the background for even greater feats of skill and daring. Likewise, we know that she will retire at the ripe old age of 17 and still have the rest of her life ahead of her. Time enough to catch up on what she missed while settling into the lower world with the rest of us. In the second photograph, time has been stopped but for an instant–time enough to reveal that the individual athlete will drop from sight. She is suspended for a brief moment of glory, and then disappears. Another will appear in her place, and another, but always as iterations of the same. The dives may differ, but the fall and much else is constant. The individual flies through the air, but the structure remains.

Photographs by Grigory Dukor/Reuters and Leon Neal/AFP-Getty Images.