I doubt that many photography class assignments include problems like this: “Imagine that you are going to photograph the chairman of the Federal Reserve; what angle should you take?” The New York Times had an interesting answer:

There are obvious reasons for choosing such an unusual approach to the chairman. Now that photo editors can choose from among 10,000 slides per day, photographers will resort to anything out of the ordinary to catch the editor’s eye. Nor was the the House Financial Services Committee hearing likely to provide much visual interest if left to its own droning routine. But neither of these considerations suggest that the photograph should have been in full color front page above the fold. So what is going on?

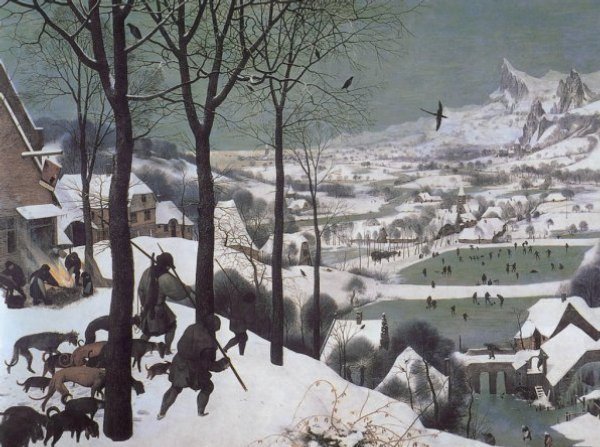

I can’t account for the intentions of those involved in production, but I can speculate about how the photograph can influence understanding of the hearing. Two things are notable: how little we see of chairman Ben Bernanke, and what we else see instead. Although just a few feet (so to speak) away from the camera, the chairman appears distant, somehow in his own space that is not directly accessible to us. The dark lines of table edge and pant leg form a V that, when framed by the top of the photograph, form a narrow aperture. It is as if we are looking through a keyhole, which is how K sees the great and mysterious Klamm in Franz Kafka’s The Castle.

Behind Klamm/Bernanke is a bare, blue-white space, as if he is on a promontory and there is no higher authority over him. He must be far from those sitting across from him as well: The caption says that he “signaled his readiness to further reduce interest rates.” We talk, but he signals, for surely his intentions are too great or mysterious to be communicated in full. As he sits alone at the heavy wood table, he is wholly indifferent to those looking up at him. He doesn’t look down on us as if to dominate us, no, that would be too much to hope for, because then we would know, or at least have some assurance, that he was aware of us and might want to, if not actually talk with us, at least contemplate the distance between us. And that distance is very great indeed.

My apologies to Franz Kafka, but the analogy still holds when we turn to the rest of the picture. K yearned for an audience with Klamm but instead had to contend with far less auspicious bureaucrats. Those standing between K and Klamm were of course the surest testament to the power of the one and the hopelessness of the other. And so we see the feet of unnamed minions from the Federal Reserve. These are the men in the gray flannel suits. Uniformity, austerity, discipline, seriousness–bureaucratic character is being performed, and woe to those who would attempt to step over these officials. And how could we, who are literally at the place where one can lick their shoes, how could we do anything but look up and beg, like a dog for a bone? Like a dog.

Photograph by Doug Mills for the New York Times. Shameless plug: If interested a further discussion of the bureaucratic style, readers might want to look at chapter five of my Political Style: The Artistry of Power.