Barbara Ehrenreich brings her book Blood Rites to a brilliant close by advancing the idea that war is a meme: a self-replicating pattern of behavior. She highlights Richard Dawkins’ observation that a meme can propagate as it does “‘simply because it is advantageous to itself.'” Her conclusion follows: “If war is a ‘living’ thing, it is a kind of creature that, by its very nature, devours us. To look at war, carefully and long enough, is to see the face of the predator over which we thought we had triumphed long ago.”

Let’s follow Ehrenreich’s injunction to look at war carefully, and do so while aware of another implication of her thesis. If war is a dynamic entity committed to its own survival, then it will adapt to elude environmental changes. Peace, prosperity, education, globalization, and similar threats need to be outflanked or infiltrated. One possible adaptation is to shift “backwards” from organized war between nation states to more primitive forms of violence. Two examples follow.

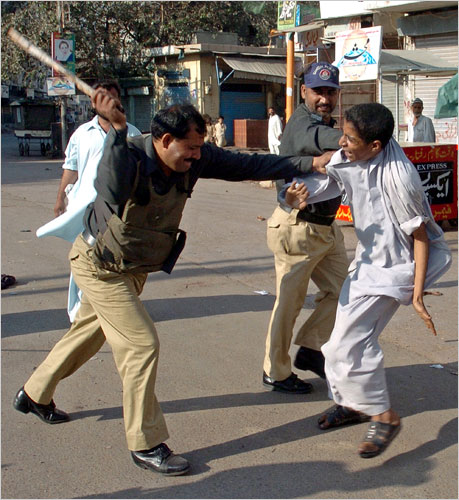

You are looking at a grown man clubbing a boy. The man is strong and practiced: holding the boy with one hand as he swings the club with full force. He keeps his eye on the target as he bring his weight into the blow. With any luck he’ll bring the thigh bone or the wrist, perhaps both. The boy can see it coming. His face is already a mask of pain and terror as he leaps to try to avoid the blow. The predator has him firmly in his grasp, however. The boy is young and thin and hobbled by his clothes; he could not be a threat to the man or to the state. He looks like at rabbit caught in the clutches of a wolf. Another member of the pack looks on approvingly.

The Chicago Tribune Photos of the Day caption said, “In Karachi, an anti-government demonstrator was struck by a police officer. There were protests in several cities around Pakistan.” The distortion is obscene. They might as well have said, “What else are the police to do when the entire county is under attack by those who would tear down the government?” Of course, the protests were on behalf of democratic government and justice, and the boy is not a demonstrator but a kid on the street who was most likely guilty only of acting like a citizen. The caption does get one thing right: state terrorism of the sort seen here–a common but mild version of the beast–is one of the forms of war in our time.

And here’s another:

I can hardly bear to look at this photo. If the young man on the ground isn’t dead yet, he’s about to be. Again, another male throws his full strength into the act of violence. His eyes are focused directly on the target–the head that is about to be crushed. Again, a bystander looks on with interest. They are in Kenya, but they could be many places in the world today. The guy with the rock is a Luo, and he is another strand in the propagation of war. This is another old pattern that has been resurgent in the past decades: rampaging violence let loose by the collapse of political and social order into anarchy. The state may still be a player behind the scenes, but in its place there is sheer destruction, mutilation, torture, and murder as done by roving bands of rogue males.

Either way boys are being ruined. And that may be the least of it. A third form of war’s predation today is the horrific rape and mutilation of many thousands of women throughout Africa. I don’t yet have the stomach to report on that. For the moment, let it be enough to look carefully at the two photographs above. They record the news but also show something worse. As “war” becomes contained, violence spreads like an epidemic. A new century is the scene for ancient forms of violence as the beast continues to devour its human prey.

Photographs by Rizwan Tabassum and Yasuyoshi Chiba, Agence France-Presse–Getty Images. The first image also brings to mind this photograph from the American civil rights movement. That image provoked strong public criticism of the white resistance in the South. But who protests similar violence on the streets of the world today?