There is something altogether uncanny about President Obama’s declaration that “America’s war in Iraq will be over” by the end of the year. And it goes well beyond the irony that President Bush had already declared “Mission Accomplished” eight years ago in 2003.

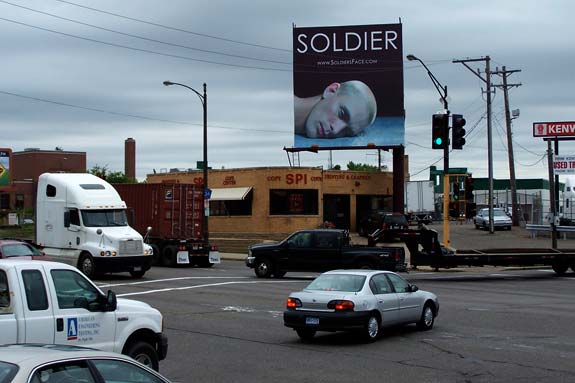

If you survey the almost constant litany of U.S. wars that have ended since the beginning of the 20th Century, their cessation is always marked by newspaper headlines with a flourish—and in the present tense: “Armistice Declared!” “Japan Surrenders, War Over!” “The War in Europe is Ended! Surrender is Unconditional.” “Korean Armistice Signed: Hostilities Cease Today.” “Peace with Honor.” In short, the declaration of the end of a war meant something more or less definitive. Or at least factual. And, of course, the accompanying photographs would typically exalt the event with all manner of celebrations, most notably the iconic image of a sailor and a nurse kissing in Times Square.

But here and for the first time we have a war that is being declared over in the future tense. We claim to know it will be over, and we can say exactly when, but it isn’t quite over yet. No one wants the ignominious fate of being the last casualty in a war before victory or peace is declared, but the concept clearly takes on a whole new meaning when we can pinpoint the future date that the war will end. One can only hope that when the war ends they will have survived–what we might call a future perfect ending to the war. I’m not sure how much such thinking will inspire confidence among the troops. The bigger difficulty, of course, is that absent a crystal ball the future is always a cognitive fiction, an imagined event, a wish dream. And this is one place where photographs enter the equation. Photographs are technically always about the past, but when we attend to them it is because we are treating the past as usable for understanding and managing the present in anticipation of an unknown future. But how exactly do we photograph a future event?

Many of the news outlets who reported on President Obama’s speech repressed this problem by simply photographing the President speaking, marking the event of his speech while ignoring its implications. But other news outlets published the above file photograph of an Army infantry division sitting in the belly of a C-17 aircraft. The captions always indicate that the photograph was taken in 2010 and that the soldiers were preparing to return home, but of course there is nothing in the photograph itself that would indicate as much. For all we know this could be a photograph of that very same infantry division as it was deploying to Iraq. The point here is not to challenge the veracity of the caption but to question what exactly we are being shown. And here what we are being shown is somewhat ambiguous, a past event being cast (or is it miscast?) as a hopeful image of the future. But really, how hopeful can it be? After all, when these troops went home in 2010 they were part of a rotation that saw other troops take their place. And how can we know that such will not be the same in the future?

We know because the President has exercised the future imperative in declaring that the war “will be over.” But according to the NYT, even as such a declaration was being made, Defense Secretary Panetta was “[holding]out the possibility of keeping a small force of American military trainers in Iraq in the future,” and there are no plans as yet to remove “4,000 to 5,000 private State department security contractors.” And more, “possibilities [are] being discussed for some troops to return in 2012.”

John Stewart of The Daily Show reported on the President’s speech by noting, “It’s finally over! Find me a nurse in Times Square.” But its not over. And there are as yet no such photographs to be taken. Let’s hope all that changes by year’s end.

Photo Credit: Maya Alleruzzo/AP