Review of Errol Morris, Believing is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography) (New York: Penguin, 2011).

One might imagine two different paths for the interpretation of photographs. From the first perspective, any photograph can provide a limited but accurate representation of the objective world: the tree really was there, as were the power lines that you hadn’t noticed when you took the picture. And, “Oh My God, did I really look like that?” Here interpretation is focused on considering how the fragmentary image could be a valid representation of a larger event. Was it altered? How much did things change before or after the 1/500th of a second in which the photograph was taken? Was the caption biased? What really happened? We might label this perspective the representational model. It constitutes the ground floor of visual literacy.

From another perspective, photography is a medium of social interaction: photographs depict people in relationship with one another, they are used to make sense of the social world, and they create and inflect relationships among those who use them. “Oh My God, did I really look like that?” is a question not only about what happened, but also about social acceptance. And about politics: in Ariella Azoulay’s terms, photography creates a “civil contract” among all parties to the photographic event and thus joins viewer and viewed as virtual citizens. We might label this model the relational model. Not surprisingly, it opens to the door to a much wider range of questions about what an image might mean, in what contexts, for what reasons, to whom.

These two perspectives are not entirely inconsistent with one another, but it is also the case that they travel in different directions—and with potentially important social and political implications. Errol Morris, a brilliant director of documentary films (e.g., The Thin Blue Line, The Fog of War, Standard Operating Procedure), seems inclined to take the first path in his recently published Believing is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography).

The volume is a beautifully written and often quite engaging set of detective stories, what Morris refers to as the “Mysteries of Photography” in the parenthetical half of the title of his book. And as others have noted, Morris is a careful (indeed, obsessive) Sherlock Holmes as he interrogates the facts of the matters before him: Can we determine where and when a photograph was taken? What is the order of photographs in a sequence of images? Is the placement of objects in a scene empirically verifiable? And so on. His answers are generally well wrought, even elegant in places. But what is notable is that the mysteries of photography are altogether secondary (literally parenthetical) to Morris’ primary concern, which, as Kathryn Schulz observed, is epistemology.

This shift from photography to epistemology is exemplified by the first half of Morris’s title: Believing is Seeing. His phrasing reverses the terms of the cultural aphorism, “seeing is believing.” This is not just a stylistic affectation. The more common phrase calls attention to the activity of “seeing” as the source of belief. As such, it carries an assumption about how we come to be (and to believe) in the world. As Aristotle remarks in his Metaphysics, “Not only with a view to action, but even when no action is contemplated, we prefer sight, generally speaking, to all the other senses. The reason of this is that of all the senses sight best helps us to know things, and reveals many distinctions” (980a). To “see” is more than just to “look” at or to “gaze” upon; to see the world is to be in it and to be of it; it is to understand the world actively and in a way commonly captured metaphorically by the phrase, “I see what you mean.” By reversing the terms Morris prioritizes “belief” as the active agent that controls seeing, and in the process he reduces the later term to a condition of passivity.

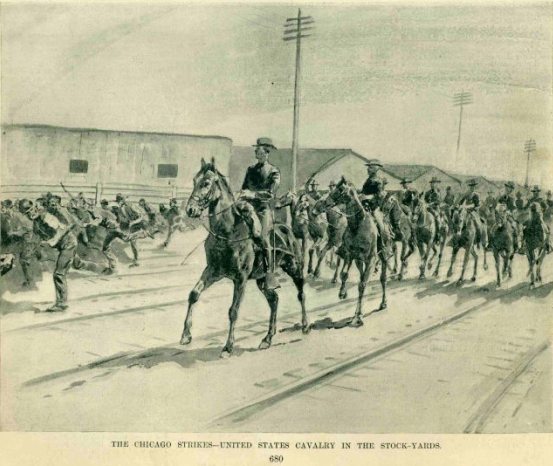

This is not just a chicken and egg question. To privilege belief in this way underscores the question of “truth.” Or more to the point, it directs attention to the relationship between truth and non-truth in fundamentally narrow ways. So, for example, in the first essay in the volume Morris attends to two famous Roger Fenton photographs from the Crimean War. In one photograph the road is covered with cannonballs. In the other photograph the cannonballs are on the side of the road. And the mystery here is, what accounts for the movement of the cannonballs from one location to the next? And which of the photographs was shot first? The first question is never fully answered, though Morris does ultimately provide an obvious answer to the second (to be fair, it is “obvious” only once it is actually figured out). But what, really, does it tell us about the truth of the matter? Or more to the point, the truth that it uncovers seems ultimately trivial when measured over and against the horrific conditions of the war that were being reported—a truth that doesn’t change no matter where the cannonballs actually landed.

Morris’ epistemological preoccupation grounds his project in the philosophical assumptions of 20th century modernism. As that context has defined photography theory, the art is singled out to bear the full weight of what could be called the burden of representation. Thus, following the example of Susan Sontag (here and here), the photograph is subjected to an intense interrogation of its cognitive value, while ignoring or at least downplaying that the same problems haunt every medium, including, most notably, the printed text. And Morris does privilege the text. To begin, we have the oddity of a book about photographs that doesn’t have a single photograph on its outer cover. This is an admittedly trivial example, but as the chapters unfold it becomes evident that the photographs can be understood only by clothing them with interviews that help to unravel the clearly epistemological mysteries. Indeed, in a chapter that focuses on Walker Evans’ photographs of a sharecropper’s cabin that appear in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the authenticity of the photograph is measured by James Agee’s inventory of what was in the cabin. Now Morris clearly acknowledges that on par we might challenge Agee’s words as less than accurate, but in the end it is those words that remain as the implicit standard for judging the photograph. And by the time we get to the final chapter in the volume, an altogether intriguing tale of the life of Amos Humiston, a soldier found dead on the battlefield of Gettysburg, the photograph that animates the story turns out to be not much more than a prop that gets us to the “real” evidence, which turns out to be a series of letters sent home from the battlefield. After all, believing is seeing, and words—not images—apparently are the appropriate medium of belief.

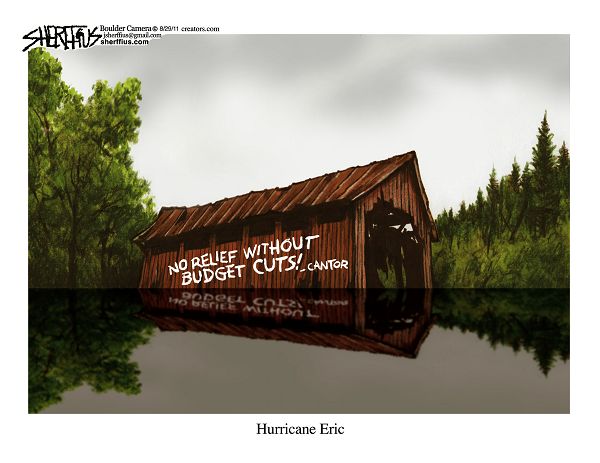

The point, of course, is not to ignore epistemology or avoid the burden of representation. We believe, however, that interpretation of the visual image should be dedicated to understanding how seeing is an active engagement with the world, and how photography at its best can communicate profound truths about the human condition while calling people into a democratic community. Of course, profundity and community each are grounded in both objective representation of the world and right relationships with other people. Thus, they don’t argue against a somewhat pedantic conception of objective truth, but one might legitimately ask how often the representational model will lead to asking and answering more important questions. Morris’ book deserves a large audience, but it also is a bit like having a literary critic who writes about nothing but plagiarism. In each case one might conclude that we are hearing about an interesting problem but still well short of taking the measure of the art.

From the relational perspective, documentary photography is not simply a mechanism for capturing the world as it is, but is rather a capacious public art that participates with all other media in making reality meaningful. And to follow this road is to recognize that the simple movement of an object in a scene—a cannonball, a clock, or a toy on a bombed out street—is less significant than the visions being evoked by the small world of the photograph. In addition, as images are circulated throughout a public culture, they can lead to important truths about what it means to see and to be seen as citizens—a result more important than whether objectivity has been sanctified one more time.

Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites

10 Comments