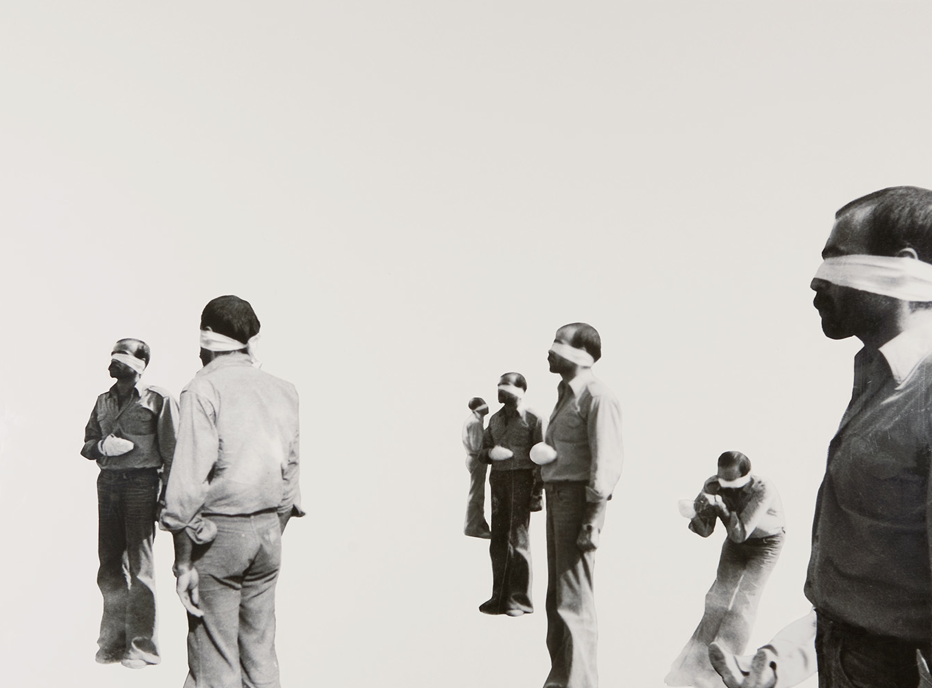

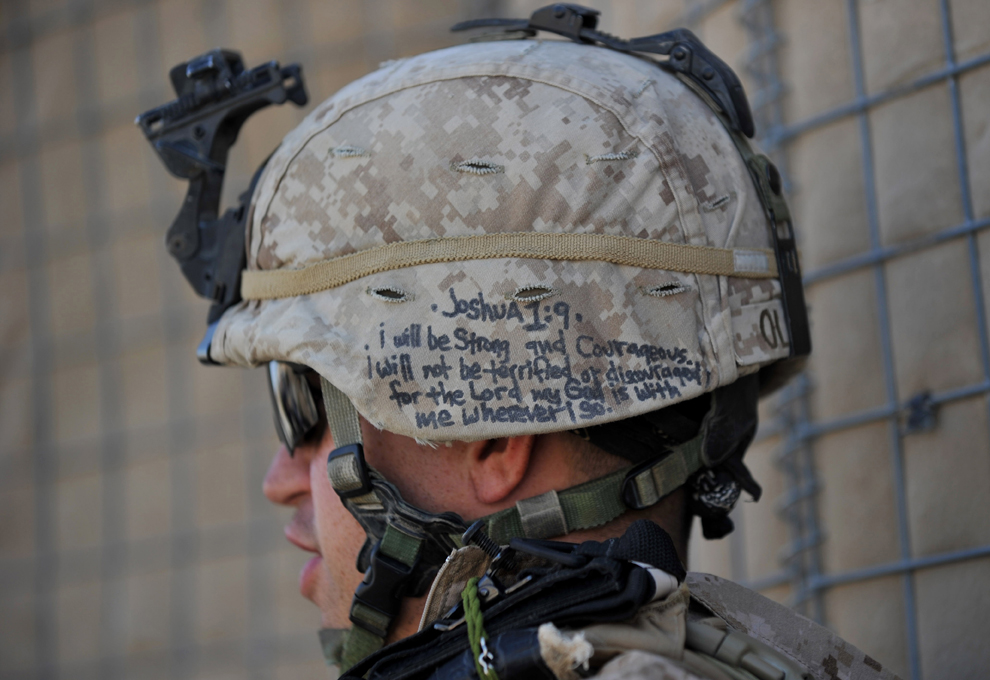

I have spent countless hours the past few days reading the many remembrances of and testimonials to the work of Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington. I knew neither of them except by their work, but that work touched me deeply, as it has many, many others, worldwide, and for me their loss is both tragic and palpable. In addition to reading about them I have also been staring at the massive archive of images that they left behind. There are so many photographs worth lingering over that it does both men a disservice to focus on only one, but the truth is that one image—by Tim Hetherington—has haunted me ever since I first encountered it in the Fall of 2007 and I feel the need to comment on it here in eulogium.

The photograph was taken in Afghanistan while Hetherington was attached to a platoon in the Korengal Valley. It showed up at the time in a number of mainstream photographic slideshows and I believe that it was included in his 2010 book Infidel (although I don’t have a copy handy so I can’t confirm that). More immediately, it has been included in many of the retrospectives of his work that have appeared in recent days (e.g., see here and here).

The power of the image is borne in some measure by its apparent simplicity as a still life photograph—an aesthetically beautiful rendering of the form of mundane, everyday objects. But of course, there’s the rub, since for those who live outside of a war zone a bandoleer of grenades is not an everyday object … let alone a mundane one. The photograph is thus dialectical in the sense that it calls attention to two different worlds, the one where the image accents the irony between form and content as if to call attention to a taboo, and the one where the image functions as something of a totem that lends order and structure—social meaning—to the community for which it serves as an emblem.

If this was simply a photograph of a bandoleer of grenades it would an unsettling, artistic rendering of the weapons of war. But what makes this an especially disturbing photograph—operating exactly at the point of tension between totem and taboo— is that the grenades are not represented as mere instruments of death and destruction, but are in fact personalized so as to identify their usage as tokens in an economy of righteous indignation and vengeance. “War,” writes Chris Hedges, “is a force that gives us meaning.” And here, we see that meaning expressed in a totemic ritual by those who are actually asked to do the fighting—the killing and the dying.

Such totemic marking is not uncommon, nor is it unique to the U.S. military, but acknowledging as much serves only to underscore the somewhat primal force that perhaps animates, and in any case unleashes, the blood lust of war. And the markings in this photograph are revealing in this regard. “9/11”and “NY” are obvious and the most easily understandable as they call attention to the somewhat iconic cause of the war, functioning in their way as “Remember the Alamo” or “Remember the Maine” might have at an earlier time. “4 Taryn” and “4 Doug” are a bit more difficult to decipher, but one might assume that they are friends or comrades whose lives had been lost either on the fateful day of 9/11 or subsequently. But what is important to note here is how such a dedication of the ordinance shifts the meaning of the war from that of an international geopolitical conflict fought between nations—or between nations and terrorists—to that of a more private, personal motivation. No longer fighting just for the nation, we fight for Taryn and Doug. “4 Mom” is the most disquieting of all, for it seems to locate the casus belli outside of specific events (9/11) or the deaths of particular individuals (Taryn and Doug) and situates it in a more fundamental cultural difference between “us” and “them” defined here as familial and generational.

It bears attention as well that one grenade is marked “free,” as if to indicate that it is not yet clear in whose name it will be used, but to imply that it is not just a technology of physical death and material destruction, but that indeed its force is no less symbolic and no less powerful and damaging for being so. And note too that the slot in the upper right hand corner is empty, the absent grenade a reminder that the photograph is not just a representation of potential power, but the marker of an active force that has already been expended.

In WW II the Office of War Information commissioned a series of documentary films designed ostensibly to answer the question “Why We Fight” as a motivational tool for supporting the war effort. Here, in a single image, Tim Hetherington seems to have raised the question once again, albeit with a different purpose. And the answers we divine should surely give us pause.

Tim and Chris, RIP

1 Comment