By guest correspondent Monica Westin

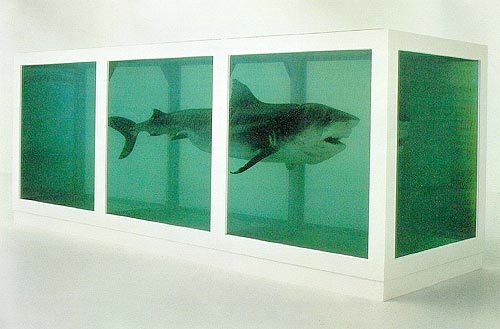

At a time when cultural production is characterized by vast range and enormous volume, it might be difficult to imagine a single image functioning as a paragon for contemporary art. And yet if I had to name an artist who stands in for contemporary art, it would be Damien Hirst. His work sells for astronomical sums, making headlines at a time when market value has become an aesthetic quality of its own. Hirst also articulates institutional critiques that both joke about the art market and take advantage of it—the logical conclusion of the postmodern artist. While Hirst’s recent diamond-covered skull has made the most headlines for its sheer cost, the image that continues to circulate the most is Hirst’s 1992 work involving a formaldehyde-preserved tiger shark, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.

The piece itself takes up and comments on contemporary art’s arguably strongest trend: to use found instances of natural or social life, and then to frame that life and repackage it as an aesthetic piece or performance. (Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics, seemingly the current bible of museum curators, is the touch point). In this case, an embalmed shark is art because it has been framed. Thus, Hirst frames both the shark and contemporary art, a subtle critique that is all the more entertaining because the shark is disintegrating.

Hirst’s earlier embalmed sheep had more or less single-handedly brought him stardom, but that work has stopped being circulated. So, embalming alone won’t do it, and one can ask, what has made this particular piece iconic? There’s an undeniable element of humor to the piece—how seriously can it really take itself?—that contributes in large part to its staying power, but lots of artworks are a bit humorous. We could analyze the piece formally: it involves an animal that, unlike a sheep, never stops moving, and so the freezing of it is a stronger framing tied to guaranteed death, making it a suspended vision of both life and death and thus a commentary on art-making. There’s the threat (of art itself?) in the open mouth of the shark, and then there’s the pop culture reference to Jaws that’s become part of collective memory. My favorite explanation is that there’s a possible allusion to cultural “sharks,” dealers in the art world, whom Hirst recently attempted to sidestep by becoming the first contemporary artist to sell his work directly at auction–which was deemed a “game changer” by anxious art insiders.

Whatever the reason, the framed shark continues to be circulated as a symbol of the current and instantaneous despite now being now almost twenty years old. Examples of this iconic status include its place on the covers of contemporary art books, from Terry Smith’s 2009 What is Contemporary Art, an ambitious and critically acclaimed attempt to catalog current movements, to The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, economist Don Thompson’s 2008 freakonomics-esque attempt to explain the art market.

Thompson’s cover doesn’t even need to reproduce a photograph of the piece, only reference it with the animal and bands of blankness where the tank’s frame would be.

Because Hirst’s shark stands in for contemporary art, it’s been appropriated and reappropriated (as has much of his work) for years in art-pop culture, as well as by other artists commenting on contemporary art. My personal favorite, from Small Artists John Cake and Darren Neave, makes a witty comment about class, democracy, and the lack thereof in the contemporary art world: Note how the scruffy janitor Lego man is scowling in front of Hirst’s multimillion-dollar half-joke, not finding it very funny.

Maybe he knows something we don’t.

Monica Westin is a Chicago-based theater and visual arts critic and editor, as well as a Ph.D. student in rhetoric at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She can be contacted at monica.e.westin@gmail.com.