Well, it is time for your NCN guys to take to the road once more, this time to attend a national communication conference in The Big Easy. And then the Thanksgiving holiday is upon us and we will both be entertaining family and friends. So we’ll be away until November 28. In the meantime, if you need a hit of that old NCN magic you might check out our brief essay on “Bad Image, Good Art: Thinking Through Banality” at FLowTV, a critical forum dedicated to promoting public discussions of the changing landscape of media culture.

Seeing Beyond American Exceptionalism

There are many reasons for the profound economic and political problems currently plaguing the US. Sure, a lot of them follow a direct line back to Ronald Reagan, and more recently the story is one of elite capture of the government to accelerate even further the massive transfer of wealth upward. American society is becoming painfully inequitable and comprehensively unhealthy, and nothing I say should detract from that assessment or from demanding accountability on behalf of the general welfare. I will say, however, that there may be additional reasons why the American public seems so passive. Why is it that “the people” are so lacking in the intelligence, solidarity, organization, and energy needed to take back their country? One answer might be, because they have never seen and can’t even really imagine this:

You are looking at the Omnilife Stadium in Guadalajara, Mexico during opening ceremonies for the 2011 Pan American Games. Quite a sight, isn’t it? Let’s say it, that’s one hell of a show in a fabulous stadium that can match or beat anything you will see on a Sunday afternoon in the US. And let’s also say that it’s not a stadium filled with illegal immigrants who will risk anything to leave an impoverished country to get to the promised land. (Mexico has serious poverty, of course, but so does the US.) Finally, let’s note that Guadalajara is not that far away from the US, but for most US citizens it might as well be on the far side of the moon.

I am suggesting that one reason Americans remain so passive in the face of economic and political predation is that they continue to believe that they are better off than the rest of the world. And not just better off, but divinely so: a nation predestined by God to become the “shining city on a hill,” as Reagan intoned, channeling the words but not the sense of John Winthrop’s 1630 speech, A Model of Christian Charity.” As many scholars have documented, America’s ideology began with the definition of the nation as a New American Adam in the New World Garden. That idea of having a special place in God’s plan and otherwise outside of the laws and vicissitudes of history has been carried forward through the doctrine of Manifest Destiny to the Lone Superpower to jokes about “Freedom Fries” and the current complacency. Carried forward, one might say, ever more unreflectively and undeservedly.

James Howard Kunstler has made a related point in Home from Nowhere, which is that American’s put up with such lousy design standards because they haven’t traveled to where higher standards are taken for granted. Americans think a city street is “nice” if it’s relatively free of litter, never mind that the few plantings are half-dead and the sidewalks too narrow for anything but funneling people between buildings. Until you’ve traveled enough, you just can’t imagine that large areas of the industrialized world look better and have amenities from free wi-fi in the airports to good trains to you name it–and we’re not even talking about health care. As Kunstler noted, when Disney World is seen as an upgrade from your normal environment, you have a problem.

And the problem only gets worse when your mind can be turned off by anyone who says that that the US is one nation under God, the greatest country on earth, with the highest standard of living in the world. If you have the facts, you can back that up a bit, but the facts will never be enough. And perhaps spectacles and monuments and city plans are not the best measure of a nation’s wealth or quality of life. I’ll grant that, but not the rest of the argument, which is one reason I like this photo.

Again, it’s visually stunning, but also something you might have seen close to home. Someone is sluicing down a waterslide in Mogyorod, a town near Budapest, Hungary. Small town, cheap entertainment, simple pleasures of a summer day–it could be anywhere, and that’s the point. What many Americans would assume is something only to be found in the US, now is a part of life for hundreds of millions of people around the globe. And if you want to push the point, the facility, structure, or infrastructure elsewhere is likely to be newer and more up to date than what’s at the end of Strip Mall Road in Middle America.

Hence, the irony: a nation long characterized by its mobility needs to get out more. Of course, geography works against it, and it’s hard to do in any case when your economic resources are going south. That’s where photography can help. The American public should come for the view, marvel at the image, and enjoy the spectacle, but they also should learn something from the experience. It appears that God’s plan is more capacious than had been thought. And if Americans don’t demand that government and the economy serve their common interests, one day they may wake up to discover that, compared to much of the developed world, they really are the exception.

Photographs by Jorge Saenz/Associated Press and Laszlo Balogh/Reuters.

Don’t Believe Everything you Hear

Google “What do the occupiers want?” and you will come up with something like 17 million hits in les than 0.1 seconds. Everyone, apparently, wants to know. The problem, of course, is that just as with Freud’s question “what do women want?,” the very inquiry is tongue-in-cheek as it presumes there is no answer that can be reasonably accommodated under the prevailing regime of logic that animates it. For Freud, of course, that was the law of the Father, and for those who challenge the Wall Street occupiers it is the logic of the market. And in each case it presumes something like a rational, oral/verbal response.

Lacking a spokesperson or unified voice however does not mean that the occupiers are without a sense of purpose or desire however inchoate it might seem to be. One simply has to observe what they are doing. That is, rather than to listen to what they say they want, one needs to see how they conduct themselves. And when one substitutes sight for sound—photographs for sound bytes—it begins to become clear on par that this is a humane, ordered, and indeed rational movement however fragmented it might be in its particular instantiations from one city or locale to the next.

Yes, it is true that the Oakland anarchists challenged this characterization in ways that give the illusion of credence to Eric Cantor’s depiction of the occupiers writ-large and across the nation as an unruly mob, but notwithstanding all of the coverage that the mainstream media gave to such—remember, “if it bleeds it leads”—the Oakland disturbances remain the aberration. The clear exception to the rule. And the rule has been the somewhat ordered development of tent cities that have been attentive to problems of nutrition, sanitation, and even health care.

Most of the photographs that we see in the mainstream media feature the occupiers in actual protest mode, holding up signs, engaging in street theater, marching or holding hands in solidarity, staring down the police, and so on. And when we see them encamped they are usually sitting on the ground or on sleeping bags looking somewhat bored. But occasionally photographs slip through that show the encampments themselves, ordered and fairly clean given the circumstances (except in those places, such as Denver, where the police rousted the tent cities and left them in shambles); or people lining up at food tables, serving and being served, and so on. And sometimes we see images such as the one above that show the members of the community working altogether rationally to sustain itself in the face of adversity. According to the caption this photograph was taken in Zuccotti park and it shows the “protestors” charging high-capacity boat batteries that have been retrofitted with small generators after the police confiscated their gas powered generators citing safety concerns. Adapt and adopt seems to be the rule.

I like this photograph in large part because it features the foot rather than the face, or more to the point, it features the shoe. Lots of shoes, actually, including the work boot, a black oxford, and an ankle boot. There may even be a sneaker in the background, though it is hard to be certain. But in any case, the emphasis on shoe and style calls attention to the pluralist world that is being organized and brought together. Race, age, and even class are largely effaced, while perhaps gender maintains some presence (but even a woman can wear a work boot or ride a cycle!). And so what we get is not a sense of the individuals involved, who remain altogether anonymous and unspoken, but the articulation of social types all seemingly working in tandem towards a common goal. Indeed, the photograph is in some measure an allegory for the body politic. But instead of an organic, idealized, or essentialist political body marked by the “official spokesperson,” we see a body politic adapted to the conditions of contemporary political life: a body politic that is fragmented, realistic, and provisional. In short, the photograph shows a conception of public life that is no longer whole—in the most traditional sense—but is nevertheless active and engaged and in its own way successful. It is, in short, an image of a pluribus without an unum, a plurality that need not be be reduced to a stultifying One. A public that is animated by common needs and goals without ignoring—or being reduced to—stylized differences.

What do the Wall Street occupiers want? It is hard to say. But then again, one really just needs to look in order to begin to figure it out.

Photo Credit: John Minchillo/AP Photo

This is Not A Declaration of Peace

There is something altogether uncanny about President Obama’s declaration that “America’s war in Iraq will be over” by the end of the year. And it goes well beyond the irony that President Bush had already declared “Mission Accomplished” eight years ago in 2003.

If you survey the almost constant litany of U.S. wars that have ended since the beginning of the 20th Century, their cessation is always marked by newspaper headlines with a flourish—and in the present tense: “Armistice Declared!” “Japan Surrenders, War Over!” “The War in Europe is Ended! Surrender is Unconditional.” “Korean Armistice Signed: Hostilities Cease Today.” “Peace with Honor.” In short, the declaration of the end of a war meant something more or less definitive. Or at least factual. And, of course, the accompanying photographs would typically exalt the event with all manner of celebrations, most notably the iconic image of a sailor and a nurse kissing in Times Square.

But here and for the first time we have a war that is being declared over in the future tense. We claim to know it will be over, and we can say exactly when, but it isn’t quite over yet. No one wants the ignominious fate of being the last casualty in a war before victory or peace is declared, but the concept clearly takes on a whole new meaning when we can pinpoint the future date that the war will end. One can only hope that when the war ends they will have survived–what we might call a future perfect ending to the war. I’m not sure how much such thinking will inspire confidence among the troops. The bigger difficulty, of course, is that absent a crystal ball the future is always a cognitive fiction, an imagined event, a wish dream. And this is one place where photographs enter the equation. Photographs are technically always about the past, but when we attend to them it is because we are treating the past as usable for understanding and managing the present in anticipation of an unknown future. But how exactly do we photograph a future event?

Many of the news outlets who reported on President Obama’s speech repressed this problem by simply photographing the President speaking, marking the event of his speech while ignoring its implications. But other news outlets published the above file photograph of an Army infantry division sitting in the belly of a C-17 aircraft. The captions always indicate that the photograph was taken in 2010 and that the soldiers were preparing to return home, but of course there is nothing in the photograph itself that would indicate as much. For all we know this could be a photograph of that very same infantry division as it was deploying to Iraq. The point here is not to challenge the veracity of the caption but to question what exactly we are being shown. And here what we are being shown is somewhat ambiguous, a past event being cast (or is it miscast?) as a hopeful image of the future. But really, how hopeful can it be? After all, when these troops went home in 2010 they were part of a rotation that saw other troops take their place. And how can we know that such will not be the same in the future?

We know because the President has exercised the future imperative in declaring that the war “will be over.” But according to the NYT, even as such a declaration was being made, Defense Secretary Panetta was “[holding]out the possibility of keeping a small force of American military trainers in Iraq in the future,” and there are no plans as yet to remove “4,000 to 5,000 private State department security contractors.” And more, “possibilities [are] being discussed for some troops to return in 2012.”

John Stewart of The Daily Show reported on the President’s speech by noting, “It’s finally over! Find me a nurse in Times Square.” But its not over. And there are as yet no such photographs to be taken. Let’s hope all that changes by year’s end.

Photo Credit: Maya Alleruzzo/AP

Can We See Through Symbols?

Sometimes there are no words, nor need there be. When I came across this image, I was instantly no longer reading a newspaper. A moment before, I had been habitually scanning for information, considering arguments, making judgments, and otherwise getting orientated for the day. And then I was in another place entirely: a place of suffering and consolation, and of both mortality and the possibility of something eternal.

I had entered a featureless room of earth tones and shadows, as if the anteroom to the underworld, only to see two sides of the human condition: one terribly exposed, and the other disturbingly dark. It seems an intensely personal moment and yet profoundly universal. One looks in vain for some way to reduce the terror lurking in the image, to learn enough so that it can be placed back into a sense of order, movement, resolution. But no face can be seen, and the light illuminating his body is absorbed completely by her black cowl.

The news was still there to be had by way of the caption: “A woman took care of a wounded relative on Saturday inside a mosque being used as a hospital by demonstrators against the government in the Yemeni capital.” The accompanying report added more. But I hadn’t seen merely a woman or a wounded relative. I had seen man’s naked, vulnerable flesh and his throat exposed as if for the slaughter. And I had seen a figure veiled in black holding the victim firmly, almost possessively, as if there were nothing else that could be done. And, of course, I had seen a pieta, the classic image in Christian iconography of Mary, the mother of Jesus, holding his broken body after it has been taken down from the cross.

The pieta is more Roman Catholic than Protestant, but though not Catholic I had no trouble seeing that artistic form as it is part of my cultural heritage. Whatever the unknown photographer may have intended, the comparison is there to be made and to motivate a powerful emotional and ethical response to the image. But should it matter that the two people in the photograph are almost certainly Muslim? Although Islam defines itself as the heir of Judaism and Christianity, the artistic traditions could not be farther apart at this point, for the suggestion that we might be looking at the image of god would be blasphemous. Worse yet, another reason the image is so powerful is that the black, hooded figure can also be seen as an angel of death claiming another soul. This demonic vision not only must be far from the truth of the scene, but also sits well with deep-set prejudice.

Thus, the dilemma: On the one hand, seeing the two figures through the cultural lens of the pieta may frame response in a manner that is profoundly appropriate. Doing so provides intense identification across cultural barriers to reach universal truths of human experience. On the other hand, transposing their experience into another culture’s symbolism can seriously distort the actual relationship of those in the photograph, while also suggesting a false universality on Christian terms precisely when one ought to be laying down such presumptions about how well people can understand one another on sight.

Thus, we need to see through symbols, but in both senses of the verb: to use them to see more than we might see otherwise, and to recognize and look past their limitations to see what they would distort or occlude. Nor is this double vision limited to matters theological.

“Libyan fighters regrouped Tuesday during the siege of Surt.” (The story is here.) Uh huh, and irregular troops taking a cigarette break is news? Once again, we are being taken somewhere else, to a place where a death’s head and the peace symbol are part of the same identity. Once again, darkness and light work together to feature two dimensions of human experience; if less complementary in principle, they are eased together by the global consumer economy. Culture in the digital age is all about mash ups, but this also could be a study in either irony or illegibility. You tell me.

Photographs by Samuel Aranda and Mauricio Lima for The New York Times.

Exchanging Prisoners Is Not Peace

I celebrate the release of Gilad Shalit from his five year imprisonment in Palestine. Five years is a long time. I don’t know him personally, but I can imagine that he has had enough of politics for awhile, and that he is looking forward to seeing his family and friends.

There should be no surprise that politics has not had enough of Gilad. This photo nicely captures the subordination of private life to political grandstanding. Gilad had his father embrace while being shouldered aside by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defence Minister Ehud Barak. The pols know a thing or two about grabbing the camera. Gilad and his dad are turned toward each other, into their private bond, while together they seem to be trying to duck out of the public eye. Bibi and Barak, not so much.

Perhaps the ministers shouldn’t be judged too harshly: the leaders on both sides are making the most of the photo-ops. Indeed, the bargain has all the marks of the conflict as a whole: Israeli leaders can talk of how each life is precious while demonstrating their unremitting resolve to protecting their citizens. Palestinians can talk of how thousands have been held in Israeli prisons while demonstrating their unremitting resolve to freeing their people. And both sides have to like the bargain: some Palestinians have crowed about how 1 for 1000 prisoners is a great deal; some Israelis will silently presume that is about the right assessment of relative worth.

And by focusing on the dramatic event, the media continue to miss the story.

Gilad is home, but every day–every single day, year in and year out–thousands of Palestinians are delayed, harassed, detained, or turned away at checkpoints that impede and sometimes prohibit travel to and from their homes. Travel to work, to hospitals, to schools, to their relatives, travel for any reason whatsoever. Political prisoners have been released from jail, and that always is a good thing, but the occupied territories remain a large, open-air prison. And 60 years is a long time.

If you look at the pictures, you can see that peace may be as far away as ever.

Photographs by the Israeli Defense Force and Musa Al-Shaer/AFP-Getty Images. For documentation from the prison guards’ perspective: see Mikhael Manekin et al., eds, Occupation of the Territories: Israeli Soldiers’ Testimonies 2000-2010 (Jeruselum, 2010), and Breaking the Silence:Israeli Soldiers Talk about the Occupied Territories.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

What Is a Revolutionary Idea?

Conservative reactions to the Wall Street protests have been hilarious, even if you don’t think of where they were with the Tea Party. House majority Leader Eric Cantor called the demonstrations “mobs,” as if he were wearing spats. Herman Cain said they shouldn’t blame the banks but only themselves, the losers who had failed–conveniently forgetting that it was the banks that failed, not the workers and students who are paying for the bailout. David Brooks chided the movement for being “small thinkers” who lack big ideas. Frankly, a just, equitable, sustainable democracy is a pretty big idea, but I’ll let that go, because a lack of ideas has nothing whatsoever to do with the current crisis. Instead, perfectly adequate ideas are being blocked at every turn by a Republican party determined to defeat Obama, destroy financial and environmental safeguards, and otherwise continue to serve the lords of capital. Small minds–and small hearts–are a problem, but it helps to get the names right.

And when all else fails, the pundits have insisted that the demonstrators are merely venting emotion, because they lack an agenda for getting out of the economic crisis. That criticism is not only lame, but just wrong. In fact, the New York Times had no trouble figuring out exactly what issues were on the table–and the Times is not exactly one of the hip new media sites. But even so, the choice need not be between protest and policy or emotion and reason. Maybe there is something else at stake.

There are many reasons to question whether the recent protests in the US–and, perhaps sadly, elsewhere–are revolutionary. In fact, it’s easy to mock them on those terms. More seriously (and as I’ve suggested before), there are good reasons to question whether those should be the terms for social and political change in the 21st century. That’s one reason I like this sign: “the new paradigm” may not be a slogan to die for, but you get the idea that we are talking about something beyond policy fixes. I’ll leave it to David Brooks to measure the size of the thinking (although see Novus Ordo Seclorum), but the idea is that if the principle of compassion were really taken seriously, we could have another refounding of American democracy to achieve a better, more decent society. (One also thinks of Gandhi’s comment when asked what he thought of Western Civilization: “I think it would be a good idea.”) But why compassion?

Neo-conservatives have been bashing compassion and (most recently) “empathy” for a couple of decades, so that’s one clue. (Their hostility to the ideal is a telling marker of their radical departure from the conservatism of Edmund Burke, and no less a figure than Adam Smith argued that compassion was the most important “moral sentiment” and essential if a capitalist society was to avoid descending into vicious self-destruction.) I can’t cover all the philosophical and political issues here, but suffice it to say, in a society given over to greed and arrogance, compassion could be a revolutionary idea.

Photographs by Velcrow Ripper and Paul Stein. Slides shows on the demonstrations are here, here, here, and elsewhere, if you want to dig around.

Cross-posted at BAGnewsNotes.

Errol Morris and the Road Not Taken

Review of Errol Morris, Believing is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography) (New York: Penguin, 2011).

One might imagine two different paths for the interpretation of photographs. From the first perspective, any photograph can provide a limited but accurate representation of the objective world: the tree really was there, as were the power lines that you hadn’t noticed when you took the picture. And, “Oh My God, did I really look like that?” Here interpretation is focused on considering how the fragmentary image could be a valid representation of a larger event. Was it altered? How much did things change before or after the 1/500th of a second in which the photograph was taken? Was the caption biased? What really happened? We might label this perspective the representational model. It constitutes the ground floor of visual literacy.

From another perspective, photography is a medium of social interaction: photographs depict people in relationship with one another, they are used to make sense of the social world, and they create and inflect relationships among those who use them. “Oh My God, did I really look like that?” is a question not only about what happened, but also about social acceptance. And about politics: in Ariella Azoulay’s terms, photography creates a “civil contract” among all parties to the photographic event and thus joins viewer and viewed as virtual citizens. We might label this model the relational model. Not surprisingly, it opens to the door to a much wider range of questions about what an image might mean, in what contexts, for what reasons, to whom.

These two perspectives are not entirely inconsistent with one another, but it is also the case that they travel in different directions—and with potentially important social and political implications. Errol Morris, a brilliant director of documentary films (e.g., The Thin Blue Line, The Fog of War, Standard Operating Procedure), seems inclined to take the first path in his recently published Believing is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography).

The volume is a beautifully written and often quite engaging set of detective stories, what Morris refers to as the “Mysteries of Photography” in the parenthetical half of the title of his book. And as others have noted, Morris is a careful (indeed, obsessive) Sherlock Holmes as he interrogates the facts of the matters before him: Can we determine where and when a photograph was taken? What is the order of photographs in a sequence of images? Is the placement of objects in a scene empirically verifiable? And so on. His answers are generally well wrought, even elegant in places. But what is notable is that the mysteries of photography are altogether secondary (literally parenthetical) to Morris’ primary concern, which, as Kathryn Schulz observed, is epistemology.

This shift from photography to epistemology is exemplified by the first half of Morris’s title: Believing is Seeing. His phrasing reverses the terms of the cultural aphorism, “seeing is believing.” This is not just a stylistic affectation. The more common phrase calls attention to the activity of “seeing” as the source of belief. As such, it carries an assumption about how we come to be (and to believe) in the world. As Aristotle remarks in his Metaphysics, “Not only with a view to action, but even when no action is contemplated, we prefer sight, generally speaking, to all the other senses. The reason of this is that of all the senses sight best helps us to know things, and reveals many distinctions” (980a). To “see” is more than just to “look” at or to “gaze” upon; to see the world is to be in it and to be of it; it is to understand the world actively and in a way commonly captured metaphorically by the phrase, “I see what you mean.” By reversing the terms Morris prioritizes “belief” as the active agent that controls seeing, and in the process he reduces the later term to a condition of passivity.

This is not just a chicken and egg question. To privilege belief in this way underscores the question of “truth.” Or more to the point, it directs attention to the relationship between truth and non-truth in fundamentally narrow ways. So, for example, in the first essay in the volume Morris attends to two famous Roger Fenton photographs from the Crimean War. In one photograph the road is covered with cannonballs. In the other photograph the cannonballs are on the side of the road. And the mystery here is, what accounts for the movement of the cannonballs from one location to the next? And which of the photographs was shot first? The first question is never fully answered, though Morris does ultimately provide an obvious answer to the second (to be fair, it is “obvious” only once it is actually figured out). But what, really, does it tell us about the truth of the matter? Or more to the point, the truth that it uncovers seems ultimately trivial when measured over and against the horrific conditions of the war that were being reported—a truth that doesn’t change no matter where the cannonballs actually landed.

Morris’ epistemological preoccupation grounds his project in the philosophical assumptions of 20th century modernism. As that context has defined photography theory, the art is singled out to bear the full weight of what could be called the burden of representation. Thus, following the example of Susan Sontag (here and here), the photograph is subjected to an intense interrogation of its cognitive value, while ignoring or at least downplaying that the same problems haunt every medium, including, most notably, the printed text. And Morris does privilege the text. To begin, we have the oddity of a book about photographs that doesn’t have a single photograph on its outer cover. This is an admittedly trivial example, but as the chapters unfold it becomes evident that the photographs can be understood only by clothing them with interviews that help to unravel the clearly epistemological mysteries. Indeed, in a chapter that focuses on Walker Evans’ photographs of a sharecropper’s cabin that appear in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the authenticity of the photograph is measured by James Agee’s inventory of what was in the cabin. Now Morris clearly acknowledges that on par we might challenge Agee’s words as less than accurate, but in the end it is those words that remain as the implicit standard for judging the photograph. And by the time we get to the final chapter in the volume, an altogether intriguing tale of the life of Amos Humiston, a soldier found dead on the battlefield of Gettysburg, the photograph that animates the story turns out to be not much more than a prop that gets us to the “real” evidence, which turns out to be a series of letters sent home from the battlefield. After all, believing is seeing, and words—not images—apparently are the appropriate medium of belief.

The point, of course, is not to ignore epistemology or avoid the burden of representation. We believe, however, that interpretation of the visual image should be dedicated to understanding how seeing is an active engagement with the world, and how photography at its best can communicate profound truths about the human condition while calling people into a democratic community. Of course, profundity and community each are grounded in both objective representation of the world and right relationships with other people. Thus, they don’t argue against a somewhat pedantic conception of objective truth, but one might legitimately ask how often the representational model will lead to asking and answering more important questions. Morris’ book deserves a large audience, but it also is a bit like having a literary critic who writes about nothing but plagiarism. In each case one might conclude that we are hearing about an interesting problem but still well short of taking the measure of the art.

From the relational perspective, documentary photography is not simply a mechanism for capturing the world as it is, but is rather a capacious public art that participates with all other media in making reality meaningful. And to follow this road is to recognize that the simple movement of an object in a scene—a cannonball, a clock, or a toy on a bombed out street—is less significant than the visions being evoked by the small world of the photograph. In addition, as images are circulated throughout a public culture, they can lead to important truths about what it means to see and to be seen as citizens—a result more important than whether objectivity has been sanctified one more time.

Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites

Inflating the National Value

I expected to see a lot of U.S. flags on display for the 9/11 anniversary and commemoration this past weekend. And of course my expectations were fully met with ersatz versions of the Stars and Stripes represented in virtually every size and variety imaginable, ranging from lapel pins to newly inked tattoos and decorated cakes to a flag the size of a football field requiring hundreds of people to manage its presentation. What I didn’t expect to see were three thousand flags clustered together in one place, as in the photograph above of Forest Park in St. Louis (and repeated in other places across the country as well).

I don’t think of myself as a curmudgeon in such matters and I do pledge allegiance to the flag on the appropriate occasions, but I also find the excess of display in the photograph above as more than just a spectacle of national hubris. Rather, it strikes me as symptomatic of a larger cultural problematic. The flag, of course, is a national symbol. And it means many different things to many different people, affecting the full gambit of civic emotions from patriotic piety to nostalgia to cynicism. But the question is, what do three thousand flags represent that a single flag cannot stand in for? Or perhaps more to the point, given the presumed gravity that we commonly grant to the meaning of the flag as the national banner–that which marks us as “one nation, indivisible,” and for which we are willing to sacrifice all–how can they represent it better?

One might see the field of flags as symbolic of the actual fatalities on 9/11, but the numbers don’t quite add up, with the official casualty count just short of three thousand, and so the potential for the mystique of identification with individual victims is not satisfied. But even if the numbers did add up, the question would still abide in some measure for the massive replication and concentration of flags in a single space has something of an inflationary effect on the symbolic currency of the national icon. And there, I think, is the rub. For there is little doubt that the symbolic value of the flag has diminished in recent years in proportion to the diminution of our domestic and international stature. The multiplication of flags in such huge numbers thus perhaps functions as something of a symbolic palliative for our current psychic anxieties about national greatness. We simply need more flags to fund our national urge.

What the photograph reminds us is that as with the effects of inflation on the dollar, the flag simply doesn’t buy as much as it used to. And more, that at some deep level we know that but don’t want to admit it.

Photo Credit: J.B. Forbes/AP Photo/St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Labor Day — Then and Now

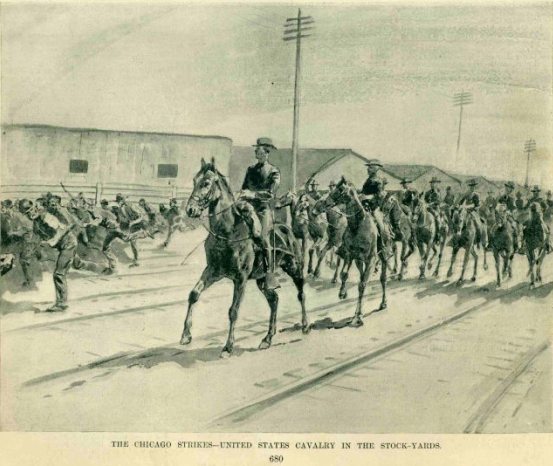

Labor Day THEN (1894)

Labor Day was signed into law as a federal holiday by President Grover Cleveland in 1894, six days after the end of the infamous wildcat, Pullman Strike when U.S. Marshals and some 12,000 U.S. military troops were ordered to Pullman, Illinois to break the strike under the pretext of enforcing the Sherman Antitrust Act and maintaing public safety. The lithograph above by Frederic Remington (no fan of the strikers who he considered “malodorous … foreign trash”) appeared in Harper’s Weekly and shows the U.S. calvary herding strikers in the stockyards. Although accounts differ, somewhere between 20 and 37 men were killed and more than fifty more seriously wounded. The declaration of the holiday was intended in large measure to appease the labor movement against the fear of further violence and subsequently became a day for celebrating the economic contributions of laborers of all sorts to the nation.

Labor Day NOW (2011)

Needless to say, No Caption Needed!