Who Shot Gabrielle Giffords?

The short answer is easy: Gabrielle Giffords was shot by Jared Lee Loughner, a resident of Tucson, Arizona. The forensic investigation will rightly be focused on him and on determining whether anyone else was directly involved in planning the attack. That is as far as causal analysis can go, and the law should go no farther. But that is not the end of the story, and any political assassination attempt raises the question of whether there might have other, perhaps unwitting accomplices. Sarah Palin, for example.

Palin’s lock and load rhetoric and use of this map at her website to target Giffords was a source of concern well before the attack and an obvious example subsequently of the how political rhetoric might be encouraging actual violence. Of course, it took no more than a day for the right to denounce any such interpretation as left-wing politicizing of the tragedy. The hypocrisy is stunning, and it is disgraceful to pretend that politics had nothing to go with the shooting. Unfortunately, the carnage in Tucson is a political tragedy and needs to be confronted directly on those terms.

Hundreds of commentators and thousands of other citizens are discussing the relationship between violent words and violent acts, and what level of civility is possible in a political culture that thrives on a volatile combination of free speech and intense competition. This discussion is necessarily political and inevitably politicized. I’m still too distraught by the shooting to say much, but a few things about the debate as it already is developing need to be noted.

First, the false equivalencies created by our professional journalists are a disservice to the republic. Over the course of history, extremism may be distributed equally across the political spectrum, but in the US–right now, right here–the violence is coming largely from the right. The threats and actual acts of violence time and again are attacks against “targets” selected because of their progressive beliefs. Although I am truly grateful that elected officials, like most of those they represent, are now standing together in sincere condemnations of violence, one side-effect of that show of unity is to whitewash the actual problem. As the press does the same, it helps to perpetuate the problem. Right wing domestic terrorism needs to be identified for what it is, and those who provide it comfort or cover need to reconsider what they are doing. What are otherwise acceptable habits of partisan advocacy and balanced reporting can collude inadvertently to normalize violence and put democracy itself at unnecessary risk.

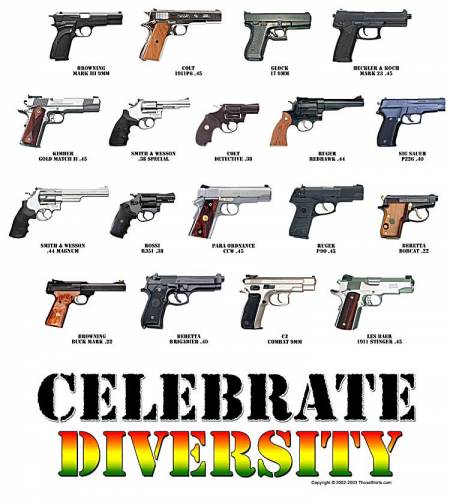

Likewise, in rightly worrying about the incendiary effects of political rhetoric, it is easy to spread the blame too widely. We may all be partisan, and electoral campaigns push everyone toward hyperbole, but not all political slogans are equally inflammatory. In the health care debate, there is a difference between saying “rising deficit” and “death panels”: wouldn’t you consider violence to protect yourself against a government bent on killing? In promoting political change, there is a difference between “change now” and calling for a “Second Amendment solution”: only the latter specifies the use of firearms. The left had its flirtation with violence in the sixties, and it lead to actual killing in Madison, Wisconsin–an accidental death that brought many on the left to pull back from the edge. Today, the right side of the political spectrum is awash with fantasies of violence–look at the web sites–and political candidates have been running ads that glamorize bearing arms and even insurrection, while right wing celebrities have been warning of government takeovers, vilifying their political opponents as traitors, and generally selling visions of an Armageddon where all personal accountability can be thrown away while defending the righteous cause.

One reason such extremism can persist is that much of the time it seems harmless. Human beings are not slaves to political rhetoric, and society is much too complex for any one message to directly cause much of anything. In fact, ordinary people can hold crazy beliefs because they don’t really have to live them: Don’t believe in evolution? Fine, as long as you still see your doctor and take your medicine. Think that Obama is plotting to place America under Sharia law? Fine, as long as you still stop at red lights. Get a kick out of Sarah’s map? No problem, as long as you don’t go around killing people.

But, of course, not everyone is wired the same way. Even so, in a different political climate Jared Loughner might have simply killed himself–a terrible thing, but not an assault on all of us. Indeed, I can’t help but think that in a society with a better health care system he might have gotten the help he needed before more deadly alternatives became possible. He is but the symptom, however, and his mental illness is not the malady that most needs to be treated. No one but Jared Loughner pulled the trigger, but his paranoia and rage will have been stoked by those who have demonized American government and endangered public officials with cheap rhetorical ploys that carry insinuations of violence.

Let me close by suggesting that the cross hairs in Sarah’s map might not be the only problem. The map itself, like the political rhetoric it was channeling, absolutely depends on maintaining a certain sense of ideological abstraction. Politics is to have only one face–that of the charismatic leader–while everything else has to be seen in terms of stock ideas (“big government”), broad generalizations (“the liberal media”), mythical places (“the real America”), ritual symbols (the Constitution), and messianic outcomes. That kind of thinking turns everything into simple formulas–which invite simple solutions. It also is profoundly anti-democratic, in this sense: democratic politics is supposed to be about ordinary people governing themselves, which they can do by recognizing each other as individuals, treating one another with the respect due to political equals, paying attention to each others’ actual experiences, acknowledging the value of compromise, and working together for a more perfect (though still fallible) union.

Those were the ideals that animated Gabrielle Giffords. And that is why, if we are to appreciate the true violence in what has happened, we need to see not a map, but her picture.

The photograph is from Reuters. The map that was at Sarah Palin’s web site has been removed; on Palin’s response to the tragedy, you might read Tina Dupuy. If you want to sign a MoveOn.org petition against overt and implied appeals to violence, click here.

Our Holiday Gift to You: Malware!

Sad but true: NCN got caught in a Google virus alert on December 16. As far as we can tell, nothing infectious was on the site, but a couple of links could have led to trouble. We’re having the site completely scrubbed and should be back to normal once the Google virus flag is removed. That can take time, however, and in any case we want to apologize for any anxiety or inconvenience we might have caused.

And what is normal? In our case, it includes our usual holiday break from posting. We’ll be back on January 10, 2011. So happy holidays and happy new year to all our readers, some of whom are shown below.

Photograph from Mercury Press. The occasion is the 2010 5K Santa Dash, Liverpool, UK.

Santa and the Problem of Public Safety

I remember as a child watching over and again the post-World War II movie Miracle on 34th St. (1947), a story about a man who looks rather like the elfish chap above and is institutionalized as insane when he declares himself to be Kris Kringle—the real Santa Claus. Claiming to be Santa Claus, it seems, can be something of a threat to public safety, and it is only with the help of a lawyer who persuades the local post office to deliver thousands of children’s letters addressed to “Santa Claus” to his client that he is able to get the state to acknowledge his true identity and thus establish his sanity. And the moral of the story was that sometimes it isn’t such a bad idea to believe in fantasies—or miracles—at least a little bit.

Of course, that was then and this is now. The late 1940s were something of an age of anxiety, to be sure, but now we live in the so-called age of terror. And today, not even an army of ACLU lawyers can save Santa Claus from the indignities of being patted and probed by the woman in uniform wearing the rubber blue glove. After all, in an age of terror anyone can be hiding a bomb inside his or her clothing: pilots, grandmothers, and even babies in blankets. Why should Old St. Nick be any different? And really, what is the loss of a “little” dignity—in some ways just another fantasy of public decorum—in the interest of maintaining national security and public safety? Or so we are told.

My initial impulse upon seeing the photograph above was to smile at the incongruity of a fantasy figure being treated by the apparatus of a national security state as if he were real and wondering who the sane and the insane might be. But then it struck me that there was nothing amusing here at all. That indeed, what we are looking at is a very real and tragic sluice of contemporary life, a world in which even our most hopeful fantasies have been taken away and no one seems to notice … or maybe even care. Notice the man on the left who doesn’t appear to be paying any attention whatsoever—or for that matter to even see—what is going on before him. Perhaps he is absorbed by the task of preparing himself for the blue glove, or maybe he just doesn’t want to get involved. But in any case, he remains passive and compliant—rather like Santa himself—and that might be the most troubling point of all as it suggests that just maybe the terrorists have already won.

Credit: AP Photo/The Repository, Scott Heckel

Sight Gag: In Memory, 1940-1980

Credit: All Hat, No Cattle

Sight Gags” is our weekly nod to the ironic and carnivalesque in a vibrant democratic public culture. We typically will not comment beyond offering an identifying label, leaving the images to “speak” for themselves as much as possible. Of course, we invite you to comment … and to send us images that you think capture the carnival of contemporary democratic public culture.

What Are the Odds?

So what are the odds that the cable internet would go out in both Indianapolis and Evanston at the same time on Sunday evening, just as we were getting geared up to write the best NCN post ever . . . and that it would stay out well past our respective bedtimes? But there you have it. But not to worry, we will be back on Wednesday.

And for the record, did we get a bit paranoid for a minute? Well, sure, but it was just a garden variety breakdown–or so they say!–at Comcast in the Midwest and in Boston and perhaps elsewhere as well. Could we have gotten around it if we had to? Sure, but we took the easy out. We’ll make it up to you later.

The NCN Guys

Behind the Facade of Modernization

Let me be perfectly clear: this post is not a criticism of either China or India. Their economic development, social services, and security measures are hardly perfect, but that is true of every society, not least the one that I know best. The images below are distinctive, however, for at least two reasons: they belie the dominant narratives of modernization and the triumph of capitalism that now define coverage of those nations and many others as well, and they expose a truth about human mortality that is never likely to be carried in the parade of well-dressed shoppers, shiny new automobiles, and gleaming office buildings that otherwise define the Asian miracle and the Indian takeoff.

Welcome to the other China, the one where 150 million still live below the poverty line. This photograph of an HIV patient could double as a template for modern poverty. Aluminum and electricity are there, but dented and run in via an extension cord. The daily calendar is there–symbol of the modern work day-but stuck on a wall where it looks like a hospital room number, a sign for a place where time only passes instead of being harnessed to measure productivity. The walls themselves have seen a lot of time pass, as they are old, chipped structures from another era.

Time passes also as our gaze is drawn slowly into the recesses of the room, which becomes an image of stasis. The man is not moving, may not have moved for awhile, may never move again. The pathway goes past the stove, then the bag of rice, then to the man himself. It is hard to imagine him getting up, measuring and cooking the rice, and walking out the door. The low-grade disorder of the table and bed is just one notch above the almost complete inertia of the scene as a whole. This is not an image of dynamic progress. The future may be bright, but in this case it is not likely to arrive in time.

And here is certainly is too late. One police officer accompanies another who was killed in a shootout with insurgents in Srinagar, India. Some hint of the vibrant street life of the subcontinent is evident outside the van, but, again, this is an image about an interior space. Although ringed with windows, the van is almost a small, funereal world onto itself, a temporary tomb for one dead body and another in waiting. And, again, the shabby seats seem to confirm the overall inertness of the place, as if nothing ever really changes there.

Others can see into the van, but the man seems to be staring blankly, as if lost to inward reflection. He has reached out a hand as if to steady the corpse, but it may be a last gesture of connection taken to steady himself inside. A gesture not evident in the first photo, but one that can be made by the spectator, were we to take the time to reflect on what is being revealed.

Political violence is the low-grade disorder affecting the Indian nation–and many more as well–and its alignment with stasis in this image is another sign of the persistence of violence within modernization. Gandhi called poverty the greatest violence, and it, too, seems to persist all too easily within modern development. Closer to home, all the marvels of the modern world will not save any one of us from death or from the isolation that can precede death. Whatever the date, at the end of the day we all end up behind the facade of modernization. As that is so, perhaps we might do more to reach out to those already there before us.

Photographs by Reuters and Altaf Qadri/Associated Press.

Visual Traces of a Democratic Public Culture

The above photograph is nearly fifty years old and I doubt that very many people recognize it—or for that matter have ever seen it before it was recently included in a slide show at The Big Picture—or can identify the event that it depicts and marks. I couldn’t. But it is nevertheless interesting for several reasons. For one thing it is a reminder of how homogenous the press corp was as recently as the mid-1960s. The site for this image is the Treaty Room in the White House and so it is possible that Helen Thomas can be found somewhere in the vicinity, but she certainly isn’t in this photograph which is not only lily white, but masculine to the core. For another thing, notice the flood lights that are illuminating the table and document being photographed, a reminder that image events and photo-ops have long been part of the political process. But what is perhaps most interesting is that apart from the journalists, there are no obvious political agents of action here. If we can assume that event marks the signing of a treaty, there is no direct evidence of who might have engineered or negotiated it and no evidence of who might take credit for it. The painting of presidents looking down upon the scene would seem to suggest that whatever victory is to be claimed here inheres in the presidency as a democratic institution and not an individual president. It is hard to imagine such a photograph being taken today.

If you haven’t figured it out by now, the photographers are huddled around the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which was signed by then President Kennedy on October 7, 1963. It was an incredibly important historical event given that concerns about above ground nuclear testing had been on the international public agenda since the middle of the Eisenhower administration in 1955. But no less important are contemporary efforts to manage nuclear arms through the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), a treaty that as recently as September 16, 2010 was endorsed by four republican members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, as well as a number of Republican stalwarts of national security, including Henry Kissinger, James Baker, and George Schultz. Even Patrick Buchanan notes that the Presidents he worked for—Nixon and Reagan—would have supported it. As of this morning, however, it appears that only one Republican Senator—Richard Lugar of Indiana—supports the treaty, while congressional Republican leadership in general seems determined to deny any and all initiatives by the Obama administration, notwithstanding any value they might have for something like national security or the possibility of movement towards a nuclear free world. Of course it is possible that Republican senators such as Christopher Bond of Missouri have good reasons to be skeptical of the verification standards built into the New Start treaty, and one can only hope that he will reveal the “secret” information he claims to have that supports his worries. Or perhaps John Kyl of Arizona is correct to try to “negotiate” for additional support to the $84 billion dollars already dedicated to “nuclear modernization” in return for his support, though its not clear how much would be enough to meet his concerns.

What does seem clear is that once a treaty is signed—and it is virtually inevitable that some treaty will be signed–whether in the lame duck session of Congress or once Republicans take control of the House in the new year we are unlikely to see a photograph like the one above where the Treaty itself is perhaps more important than those who brought it into being. And for future generations looking back on the politics of this time that too will offer interesting evidence of the state of our so-called democratic public culture

Photo Credit: Robert Knudsen, White House/John F. Kennedy Library

On The Road Again

Well, your NCN guys are on the road again.

We’ll be back right after the Thanksgiving Holiday on November 29th.

Veterans Day, November 11, 2010

In hailing the end of World War I President Wilson declared “Armistice Day.” In 1938 the U.S. Congress designated it as “a day to be dedicated to the cause of world peace.” It was subsequently renamed “Veterans Day” in 1954.

Credit: Steve Breen, San Diego Union Tribune