The close conjunction of Earth Day and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf should not go unremarked, and as more than an occasion for irony. Disasters have the virtue of exposing the hidden costs of old habits, not least habits of seeing. So it is that a slide show at the Manchester Guardian provides not only a counterpoint to the mess in the Gulf, but also an inadvertent example of how meaningful change has to go beyond strengthening government regulations and refining extraction technologies. Such changes are needed ASAP, but there also is need for cultural change if a sustainable civilization worth having is going to emerge in the 21st century.

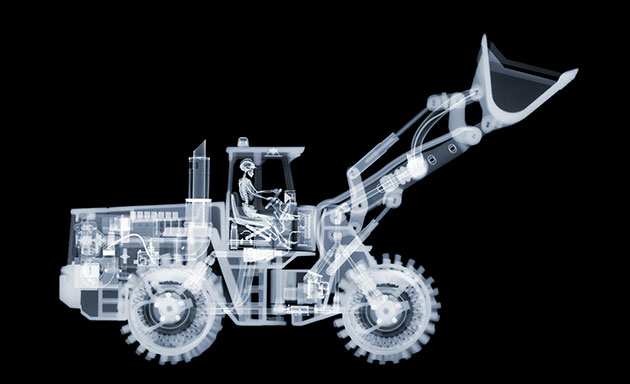

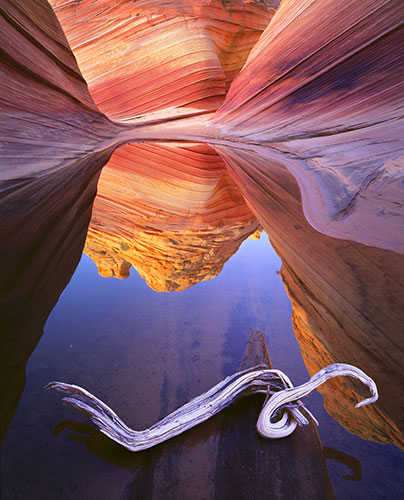

The Guardian asked the world’s leading “professional conservation photographers” to select the top forty nature photographs of all time. Those images were then auctioned off in conjunction with Earth Day to raise money for a suitable charity. You can see ten of the images here. Frankly, I would find it very hard to pick the top 1000 nature photographs, and my list could very well not include many of those at the Guardian, but that’s a small matter. What was striking, to my mind, about the ten photos selected for the Guardian slide show was that four of them were double images, such as the one above, and five were images of multiple members of a single species, with the image below combining both elements.

Not to put too fine a point upon it, but both images are highly unusual. Nature is not a hall of mirrors, nor do species live primarily among themselves. Even if we grant each figure its due–as all nature from crystals to organisms involves reproduction, and many species are social species naturally oriented toward those within the group–there is something decidedly crafted about the professional photographs. The two above, for example, are masterful studies in composition that are the result of considerable effort and adroit camera work, and they bring the viewer to a highly privileged vantage for seeing nature in its most revealing moments, whether with the clarity of dawn or the intimacy of twilight. I am the last person to fault such images for their beauty, yet I can’t help but notice how much these images are about photography itself.

Photography is an art of reproduction. The photograph is a copy of what is seen through the lens of the camera, and the photograph then can be copied many times over. The ten nature photographs in the slide show certainly reflect the idiosyncratic preferences of some photo editor, but their uniformity also discloses how much the human spectator can’t help seeing itself reflected in what it sees. Nature, it seems, is a version of photography: always doubling and multiplying further to create reproductions of itself. This is what has been called “the world as picture”: the world taken as if it did not exist unless it can become a picture, finally most real when it is seen as an image.

This is an indirect way of saying that we can’t help but seeing the world on our own terms. And how nice is it to think that nature has a formal structure that can be perfectly captured by modern technology, and that large, intelligent, social animals can serenely dominate the landscape. But, of course, only the camera leaves a scene untouched, and the pathos of the elephants is that an intelligent species can find itself at the last watering hole.

Some might point out that “nature” is a human construction and subject to criticism on those grounds. Even so, it is fair to ask whether photographers or anyone else have really seen nature, and how familiar images reflect a particular way of seeing that might be shaped too much by cultural habits. Those habits currently may encourage contemplation, but at the cost of seeing other species apart from us and defined primarily by their own prospects for reproduction. By contrast, the techniques and sensibility of an ecologically sensitive photography might lead to a different way of seeing nature. That perspective could not escape its own projection of human interests onto the image, but it also might feature interdependency rather than species standing alone, and complexity that is more dynamic and even more beautiful and more profound than what can be caught in mere reflection.

Photographs by Jack Dykinga and Frans Lanting/Corbis-iLCP.