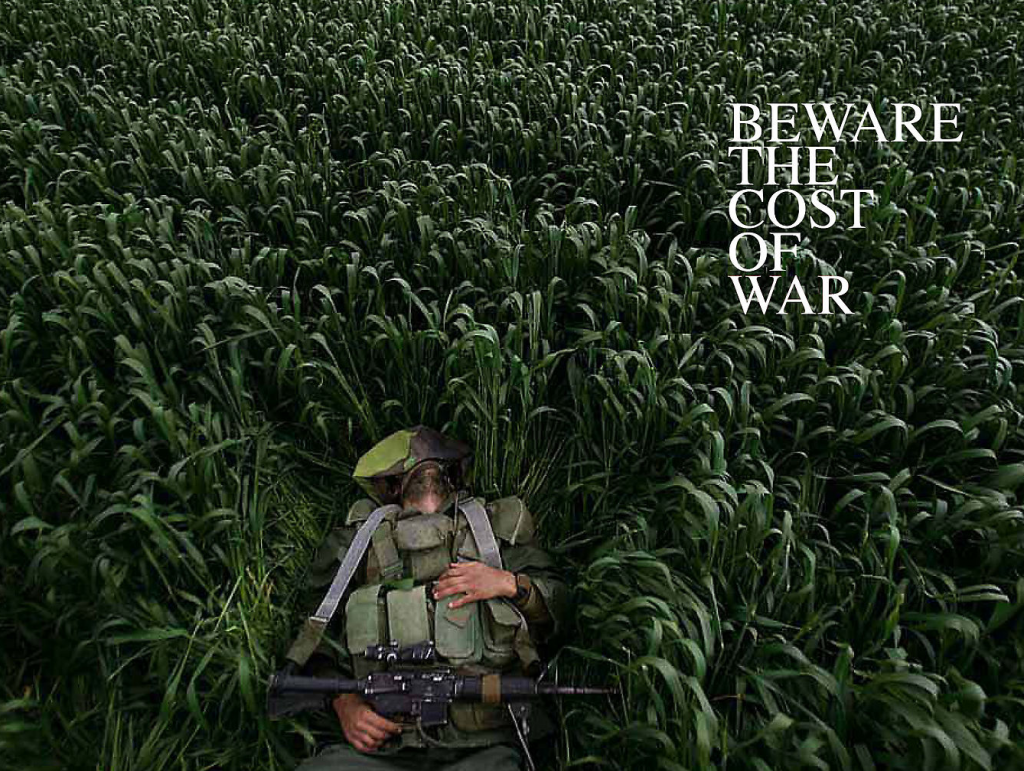

November 11th was originally proclaimed Armistice Day by President Wilson in 1919 as a day for remembering those who sacrificed their lives in the first “war to end all wars.” In 1926 the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution in which November 11th was designated as a day for commemorating “with thanksgiving and prayer exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations.” In 1954 Armistice Day was renamed “Veteran’s Day” by President Eisenhower in order to acknowledge and honor all veterans in the wake of World War II and the Korean conflict. The movement from commemorating a “war to end all wars” in the name of peace, good will and mutual understanding to a day for honoring Veterans of all wars without prejudice is not subtle, although we rarely if ever seem to acknowledge the difference. The point to be made here, however, is that this very shift in meaning correlates in no small way with the difficulty we have had in recent times in judging any national military aggression lest we risk doing harm to those who actually do the fighting.

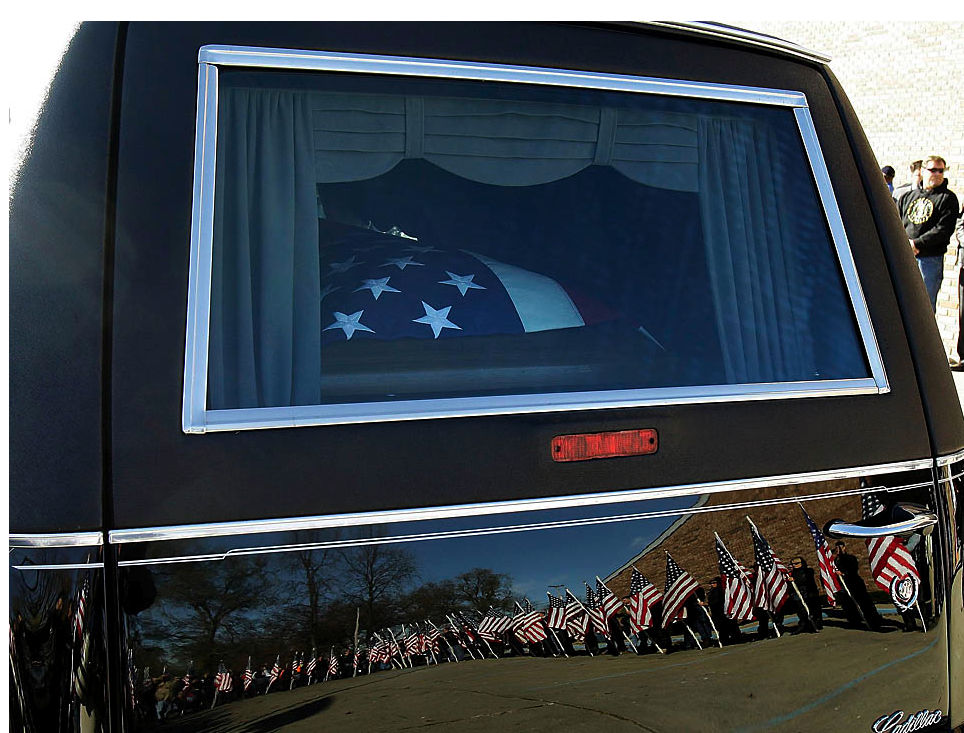

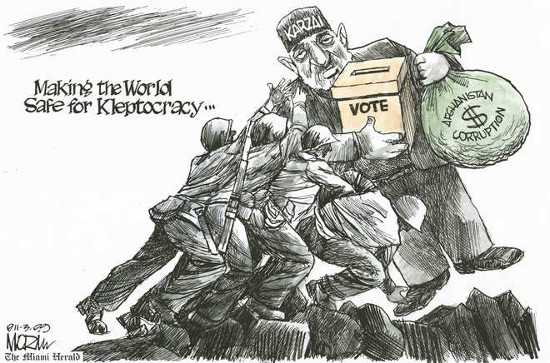

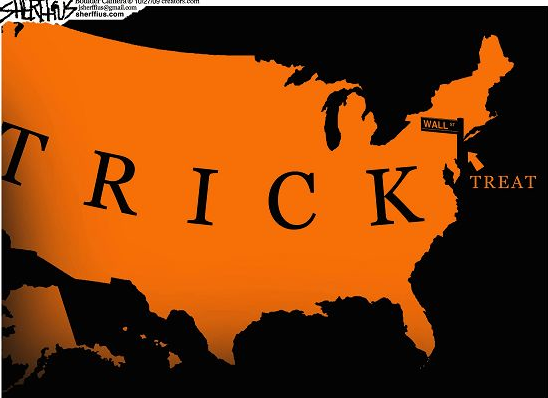

The many slide shows at mainstream journalistic websites marking Veteran’s Day this past week make the point, as photograph after photograph presents visually eloquent and decorous displays of the sacrifices of those who nobly served and often died in the service of their country without any specific reflection on the particular wars being fought. This battle, that invasion, it doesn’t really seem to matter, as the reasons for fighting are visually trumped by an abstract, visual display of national sacrifice that, in the end, reduces the individual to the nation-state. The photograph above from the Wall Street Journal is a case in point. The hearse carries the flag draped remains of a soldier recently killed by a roadside bomb in Afghanistan. There is nothing in the image that marks that fact, although the caption does give the deceased’s name and rank, but notice how the photograph itself works to deflect attention from the particular sacrifice inside the hearse to the wall of flags that extends to infinity reflected on the vehicle’s highly polished, exterior surface. The hearse is thus cast as a mirror, and as the photograph invites us to view it as such, what we see—as with any mirror—is a reflection of ourselves. And what that reflection reveals is not the individual per se, but the nation signified by an inexorable march of the flag. Whatever specific cause took the life of this soldier seems to pale in comparison, and certainly is not subject to question.

A second photograph from the same paper on the same day underscores and extends the nationalist implications of the first image above.

Here we have a boy who is described without a name as a “Junior Reserve Offices Training Corps honor guard” participating in a Veteran’s Day ceremony. Lacking a name, he takes on the quality of a individuated aggregate—an individual cast in the role of a collective. He stands for something more than himself. But what? The eyes, we are told, are the windows to the soul. But here, notice that his eyes are hidden from view; if he has an individual soul it is not accessible to us. What we have instead is his serious countenance defined by the set of his jaw balanced against the bright, mirror-like surface of his highly polished helmet, an instrument of war turned to ceremonial purposes. The helmet reflects both the deeply saturated colors of the national flag that he appears to be holding, and which shrouds his head and shoulders, as well as another flag, more difficult to make out, that appears to be in his line of vision. There is no hint of the boy here, let alone the individual veteran, but a connection between past (behind him) and future (in front of him) defined only by the national colors. His (and our) present is defined by a direct line from past to future and the trajectory is … well, fated. And once again, the flag marches on.

We can and should remember those who sacrifice their lives for the common good. But in doing so we are well advised to recognize and reflect on what is being sacrificed to what, and to avoid the temptation—however comforting it might be—to make a fetish of the flag and what it represents in the process.

Credit: Darron Cummings/AP; Nati Harnick/AP