In the classical tradition “decorum” called attention to the linguistic, aesthetic, and ethical standards of propriety designed to coordinate the relationship between thought and expression. The eloquent orator was decorous when he performed his civic persona in a manner that seamlessly and invisibly embodied a style of expression and a substance of thought that was appropriate to the audience and occasion being addressed. More than just a set of rules for eloquent speaking, however, decorum was understood to be a normative habit of civic participation that would animate the balance or harmony “necessary for the comprehension and direction of life in the pluralistic space of public experience.”* It was, in short, a control against unrestrained ego necessary to managing the tension between individual desires and collective responsibilities in civic life.

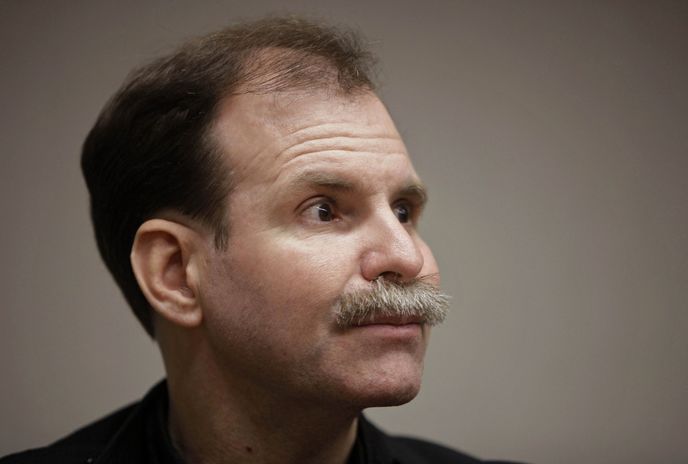

The photograph below depicts the fundamental problem of the late governorship of Rod Blagojevich as a failure of decorum—a complete and utter lack of civic harmony.

We like to think that the conduct of our leaders will call us to a higher standard of public responsibility as citizens, an entailment, perhaps, of the assumption that as elected servants of the public they are temporary stewards of an office that is larger than themselves. We often accent this assumption by talking about how an elected official will “grow into the position,” underscoring both the sense in which the office transcends the mortal embodiment of any one person, as well as how the formal demands of the office shape and control any given occupant. But in this photograph—which occupied the four middle columns, above the fold on the front page of the NYT on the day that Governor Blagojevich was unanimously convicted on an article of impeachment—none of these assumptions seem to abide.

A governor’s office is a public, symbolic space, its size and visual tableau functions as a marker of its long standing history and civic power, a reminder that the “office” is bigger than the current office holder. Here, however, the photograph diminishes the effects of such magnificence by photographing the governor in a relatively tight, middle-distance close-up. Indeed, the photograph contradicts the assumption that the office is bigger than the man by making it seems as if the physical space of the office can barely contain him, a point further accentuated by his slumping posture, as if the chair is too big for him and he never grew into it.

But there is more, for one might expect to see the governor’s office festooned with the emblems of the state—flags, the state seal, artifacts that mark the state’s history, and quite possibly photographs of the sitting governor as he conducts the business of his office. And surely such things exist somewhere in the office. But here, however, there is none of that. Instead, the governor is triangulated by a small bust of Abraham Lincoln, a much larger, statuesque figurine of Elvis Presley (that recalls the ridiculous photograph of President Nixon posing with Elvis in the Oval Office of the White House), and a framed snapshot of Blagojevich, the private citizen, with his children. Decorating one’s workspace with personal effects is a habit of contemporary life, but even in the private sector the assumption is that such artifacts will operate moderately, in the background, visible and yet not seen—hence decorous. One would anticipate even more such moderation in the governor’s office, but here the emblems of personal eccentricity and private life dominate the mis-en-scène almost to the point of impropriety.

What gives the photograph its dramatic force, and in the end what pushes it fully beyond the bounds of propriety, is the shoe poised awkwardly and somewhat precariously on the edge of the desk. Truth to tell, I will occasionally put my feet on my desk in my office when I am reading a manuscript or talking on the phone. But I would never do it if someone else were in the room, and certainly not if there was a photographer within viewing distance (let alone a NYT photojournalist). And the reason is quite simple: doing so marks the space as private and proprietary. To do so in an otherwise public space is a sign of arrogance and disrespect; to do so as an officer of the state, literally posing for the a NYT photographer, marks the behavior as a gesture, as an intentional performance of utter contempt for the office and all who might see it.

More even than Blagojevich’s absurd claim to the NYT reporter that “[we] should have been more selfish, not selfless,” the photograph is a representative (visual) anecdote of the deep habits of his governorship and why he is deserving of public opprobrium whether he is guilty of the formal charges against him or not. More, it is a reminder of why the standards of public decorum are valuable guides to the harmony and ministrations of civic life.

Photo Credit: Amanda Rivkin/New York Times

*Michael Leff, “The Habitation of Rhetoric” in Contemporary Rhetorical Theory: A Reader, ed. John Louis Lucaites, et al. New York: Guilford Press, 1993, p. 62.

2 Comments