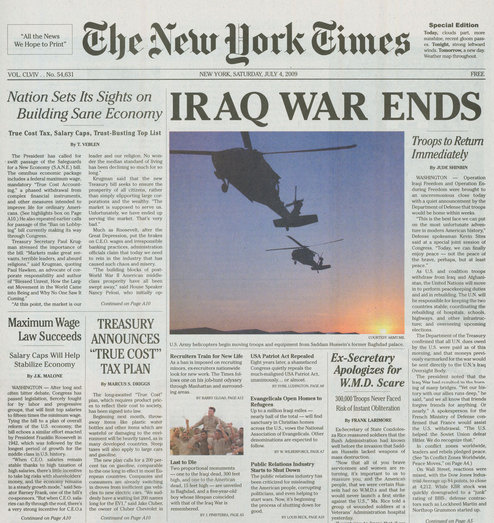

I have written previously about the regularity and profusion of photographs of children in the Middle East—Israeli, Pakistani, and Iraqi children in particular—playing with toy guns. Such images operate in a somewhat allegorical register as they invoke one or a number of ironic, dialectical incongruities between child and adult, innocence and maturity, play and reality, the pleasure and horror of war, plasticity and steel, “their” present and “our” past, and so on. This photograph seems to capture all of that and something more.

The caption reads: “An Iraqi boy holds a toy gun during a joint American and Iraqi military security sweep in the neighborhood of Sariyah in Baghdad, Iraq.” The key to the image, however, is in recognizing that the toy gun is incidental to the scene that that we are witnessing. The boy holds a toy weapon, to be sure, but he does so awkwardly as if he doesn’t quite know how to use it, and in any case he does not hold it in a manner that might be thought of as threatening—or even effective. Nor is it the toy itself that draws the viewer’s attention—the caption to the contrary notwithstanding—but rather the young boy’s gaze. But what could he be looking at? What does he see? And where have we seen this image before?

Of course, we cannot know for sure what he is looking at. But the soldier standing behind him is Iraqi, and the boy is clearly not looking at the photographer, who is positioned at an oblique angle to the field of vision. Given that the caption identifies this is a joint Iraqi-American “military security sweep” it stands to reason that the boy has fixed his gaze upon the American soldier—or at least that is what the interaction of image and text invites us to imagine. And what he sees there is clearly something that pleases and inspires him. Indeed, it is the look of a child’s wonder, perhaps even hero worship, as if in the presence of a powerful and incorruptible majesty. One might discount it as the misdirected gaze of youthful innocence and naiveté but for the fact that the family members in the background giving their smiling approval to the scene that unfolds before their eyes as well.

The young boy’s gaze is not new to us, at least not to those of us who were raised with the myth of the American west, where physical strength and a skill with six-guns (and the resolve to use both when necessary) served as individual virtues necessary to taming an otherwise dangerous frontier and to making the world safe and secure for democracy and domesticity. Indeed, the boy’s gaze almost perfectly mirrors the look of Joey Starrett in the 1950s western Shane, the young boy (played by Brandon DeWilde) who worships the title character—a somewhat mysterious stranger with a gunslinger past that he is trying to forget nevertheless draws upon his strength of character to save the homesteading community from a brutish cattle baron—for precisely these virtues. At the end of the movie, after having completed his work, Shane moves on, even as Joey cries “Shane! Come back!” for he knows that there is no place for him in the world that he helped to make safe.

It is highly unlikely that the photographer knew of or was modeling a sluice of U.S. popular culture circa 1950, but given the ways in which the Bush administration has framed the intervention in Iraq from the very beginning as an extension of our history as a gunfighter nation, the analogy—what biblical hermeneutical scholars might call an anagogical relationship or “in spirit” comparison—is apt. And the current situation in Iraq makes the Shane myth all the more attractive as an interpretive frame for those who think of the U.S. military as the western hero carving out a path for civilization in the wilderness, leaving behind a feminized and domesticated community beholden to the those with the character and resolve to do the hard work at great personal expense. As the U.S. allegedly prepares to leave one can hear this young boy’s plea to stay. We can only hope that the incoming administration has the same good sense of Shane to realize that he has to move on

Photo Credit: Hadi Mizban/AP