The Florida primary is upon us this week, and many are predicting that it could be the last hurrah for Rudy Giuliani’s campaign. We’ll have to wait and see. But as I was listening to the Sunday morning pundits yesterday I was reminded of two photographs that appeared in a NYT on-line slide show a few weeks back, as the ex-Mayor of New York was campaigning in Miami while everyone else was in New Hampshire.

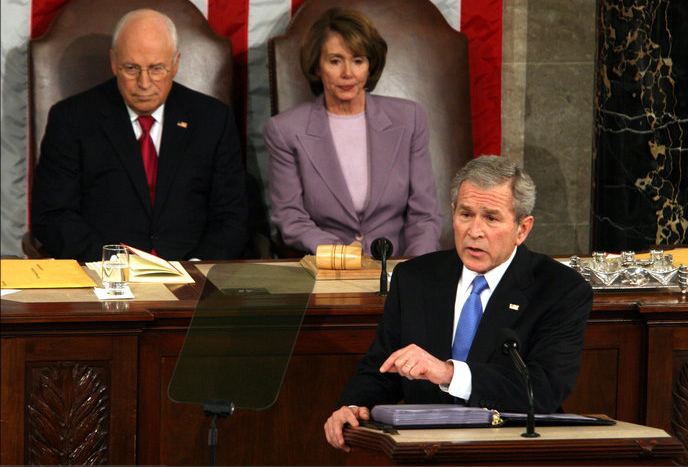

The first shot looks to be a scene from a small town Fourth of July celebration where congressional representatives frequently show up to press the flesh and to be seen with local political dignitaries. Parades are typically the order of the day, and they usually include marching bands, local civics organizations, fire trucks with their sirens screaming, and, of course, an abundance of red, white, and blue. There are usually lots of young children running around, and a good time is had by all.The parade in this photograph, however, does not take place in small town America, but rather Miami’s “Little Havana.” And the event is not the Fourth of July, but the annual Three King’s Day Parade, a traditional Hispanic holiday that honors the Epiphany; in Miami it is attended regularly by more than 400,000 people. Here the ex-Mayor rides on an antique fire truck festooned with campaign posters (an odd adornment for a religious festival, but it is the political season!). The sky is blue, sprinkled with white clouds, the American flag flaps in the breeze, and a smiling Giuliani poses at the front of the truck, in charge as if leading an army. One is reminded of the scene from the movie Patton where General Patton leads his troops into Messina after liberating it from the German occupation. Like Patton, Giuliani doesn’t wave, but stares directly ahead, his purpose more to be seen than to see. The picture suggests that all is well, and we can almost hear the cheering crowds. After all, “Florida is RUDY country.”

The immediate next frame in the slide show, however, tells a somewhat different story.

Here, presumably, we see what the candidate and his entourage would see if they were actually looking. The crowd, of course, is sparse; indeed, it is no crowd at all. If there were hundreds of thousands of people at the celebration earlier in the day, they have now dispersed. And the remaining stragglers don’t seem to be in any mood to cheer. Indeed, what is marked is the utter lack of enthusiasm for the passing scene: The attention of the child in the lower right is distracted by the person standing next to him, but then he is a child and no doubt easily distracted; but notice the man in the upper right, who has his back turned and is walking away—he seems to be carrying a camera, but apparently the scene on the street has no interest for him, even if it does include a presidential candidate. Others seem to be looking in the direction of the passing fire truck, but for the most part their expressions are blank, totally devoid of any affect or interest. It is hard to know what any of them are thinking, but it is equally hard to imagine that they are going to rush out to vote for Giuliani.

What is most conspicuous, of course, is the adolescent boy posing in the middle of the scene. Apparently standing on the parade side of the barricade (which is also the camera side of the barricade), he is separated from the folks that surround him. His bright red hat and t-shirt add a modicum of affect to an otherwise drab and visually muted scene, and if there is anyone the viewer is invited to identify with in the picture it is surely him. Like Giuliani, he too seems to be performing a role. But while the candidate seems to fashion himself as something like a liberator, the youth leans against the barricades with an attitude that is in equal parts nonchalance and arrogance—one is reminded of a young Marlon Brando in The Wild Ones. The tilt of his hat marks him as someone who identifies with hip hop music and the gangster culture it has spawned, hardly a demographic that one would imagine the Giuliani campaign works very hard to cultivate—a point which doesn’t seem to be lost on the boy. And what is most noticeable is the look of utter skepticism and disdain, as if to say, “how dumb do you think we are?” The contrast between the two photographs could not be more pronounced and their contiguity suggests that they should be read in dialogue with one another.

The point I want to make is a minor one, and it has more to do with developing a sense of visual literacy than it does with what seems to be the ill-fated Giuliani campaign for President. The pairing of these two images in a slide show produces what cinematographers call the “shot-reverse shot.” It is a fairly common technique (or visual logic) for filming a dialogue between two people. The camera focuses in middle distance on an individual talking, it then reverses its orientation on what appears to be a 180 degree pivot to show another person talking, creating the effect of a dialogue that moves back-and-forth. The larger effect is to identify the external viewer (i.e., “you”) with the point of view of the internal viewer; and because that point of view switches back and forth in a coordinated series of reversals, the external viewer is positioned as an omniscient spectator who presumably sees all that there is to see. It is, of course, an illusion troubled by many entailments, not least the assumption that the suture between shot and reverse shot is seamless and transparent, that there is nothing in the space between two frames that effects the meaning of their relationship. The illusion here is especially pronounced in cinematic representation, where the cutting back and forth is often quick and adopts the register of real time, but it can be no less effective in the placement of still images next to one another in a slide show, especially in a rhetorical culture habituated to the visual logic of shot-reverse shot.

The assumption in linking these two photographs together in imitation of a shot-reverse shot sequence is that the spectator will recognize that Giuliani sees the dwindling audience, the bored citizens, and the disgruntled youth, and yet he continues to smile anyway as if they aren’t there or don’t really matter; or worse yet, he simply doesn’t see them at all. In either case, the effect is thus a visual argument that coaches an attitude of cynicism towards the Giuliani campaign who seems to refuse the opportunity for dialogue. But of course this assumes as well that the two images were shot at roughly the same time and that they actually exist in physical proximity to one another. What if they were actually shot minutes or hours apart? Or at different places along the parade route? I have no reason to suspect foul play here—largely because past experience tells me that the cyncism is well placed—but the point is that there really is no way to tell what the time-space relationship of the two images might be without actually having been there. And of course that is not always a possibility. The value of the photographs as positive evidence of something like objective truth is thus mitigated.

This does not mean, however, that we should disavow the power of the photograph (or the slide show for that matter) to represent the social or cultural truth of such events or to invite insight into the complexities and nuances of social relations. Indeed, much to the contrary, we believe here at NCN that the artistic use of photography is a vital component of a vibrant democratic public culture—quite literally a way of showing us what it means to see and to be seen as citizens. What it should remind us, however, is that as a technology of communication the photograph is not so much different in its power and capacity to represent or constitute the world than is the technology of the “word”: neither offers unmediated vision, and both rely equally upon a critical understanding of formal and cultural logics of articulation (such as the shot-reverse shot, but much more as well), genres and conventions of representation (such as the common metaphors and narratives used to represent political campaigns, youth culture, etc., including often vague references to history, popular culture, and the like), a sense of ethos, etc. Additionally, and perhaps more important, it should remind us of the responsibility we have as citizens to make critical judgments about the messages we encounter and the assumptions that they draw upon, regardless of the media in which we encounter them.

Photo Credits: Eric Thayer/New York Times

6 Comments