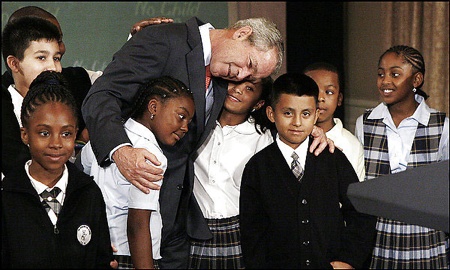

A recent New York Times report on the Korean summit meeting was captioned with this photograph:

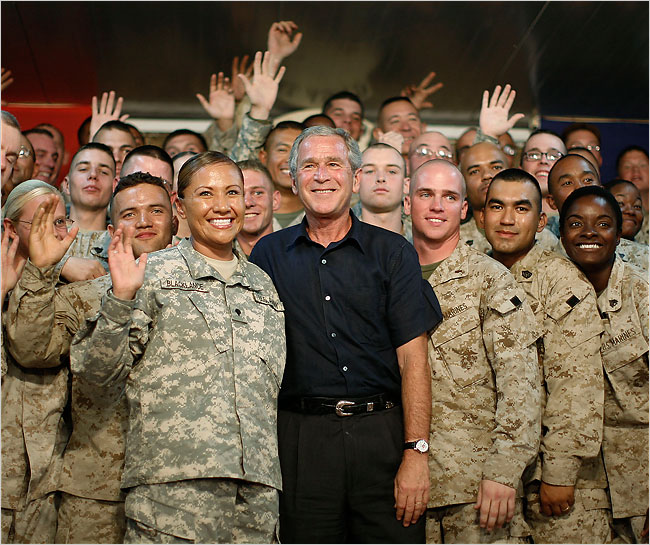

We are seeing the South Korean president returning home. For a moment, I thought it was taken in North Korea, where the Glorious Leader is regularly surrounded by the conventions of visual propaganda that you see above. Then again, it also could have been taken in the US:

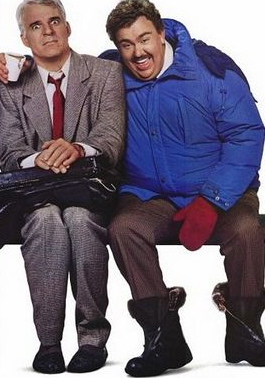

As Michael Shaw pointed out at BagnewsNotes, these carefully posed images become even more incredible now that Bush has vetoed legislation to extend health insurance for children. Unfortunately, we know all too well that this president knows no shame. It might also be interesting to note how his use of kids as props puts him in interesting company. Guys like this, for example:

For all I know, Lenin may have done more for school children than Bush ever will, although that’s not saying much. It is clear that they both had the time to pose with kids for propaganda photos that were used to cover draconian policies. (This one is from a magazine accompanying the occupation of Latvia.) What remains to be shown, however, is where the template probably comes from, which is this iconic tableau:

The image of Jesus with the children refers to a story told in Mathew, Mark, and Luke (Mat. 19:14, Mark 10:14, Luke 18:16). When his disciples had stopped those who were trying to bring children forward for a blessing, Jesus rebuked his self-appointed campaign managers. The scene has been reproduced in various images countless times in many art forms, high and low. It will have been put to many uses, including church propaganda and social hegemony. (For the record, Jesus will not have been blond.)

There is much that could be said about the relationship between the religious icon and secular image-management. Let me just note two things: First, there is no indication in the story that Jesus posed with the children. As Mathew tells it, “he laid his hands on the children, and went his way.” Second, the point of the story is not that Jesus liked kids or that they liked him. No, the story is about gatekeeping. To say that “the Kingdom of Heaven belongs to such as these” meant that no one was barred from that Kingdom because they lacked status or power. In welcoming the children–and rebuking those who would keep the weak, dependent, or socially inferior out of sight–Jesus was upending the hierarchies that structured that society. That idea has been forgotten when kids can become props for sham displays of compassion by cynical rulers.

Photographs: pool photo; Charles Dharapak/Associated Press; back cover of ”Darba sieviete” magazine, # 1, 1940. Stained Glass window from Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Roman Catholic Church. My reading of the Biblical text is indebted to Albert Nolan, Jesus Before Christianity. The quoted text is from the New English Bible.