Nothing that I’m about to say is intended to make light of the terrible bombing in Boston on Monday. Nothing. And I’m not really going to talk about Boston; after all, what needs to be said that hasn’t been said? Neither words nor pictures are needed to depict the carnage, the splendid response by both first responders and ordinary citizens, or the sorrow, anger, and other emotions still swirling through the city and the country.

There is need, however, to learn what one can and to share it with others. This may not be the best time to say it, but it’s the time I’ve got. My point is simple: what was a unique, unexpected, unjustified, traumatic event in the US is something that is happening all the time in Iraq, and as a direct consequence of the American invasion and occupation.

The New York Times reported in 2011 that suicide bombings had by that time killed over 12,000 civilians in Iraq, while over 30,000 had been wounded. Imagine, if you can, more than 12,000 dead. That is the three deaths from Monday multiplied by 4000, as if you had a Boston Marathon bombing every day for 11 years, and all that in a country with a smaller population than the US. And it didn’t stop n 2011. On the same day as the marathon, the Times reported that bombings were increasing again, including “more than 20 attacks around the country on Monday” that “killed close to 50 people and wounded nearly 200.”

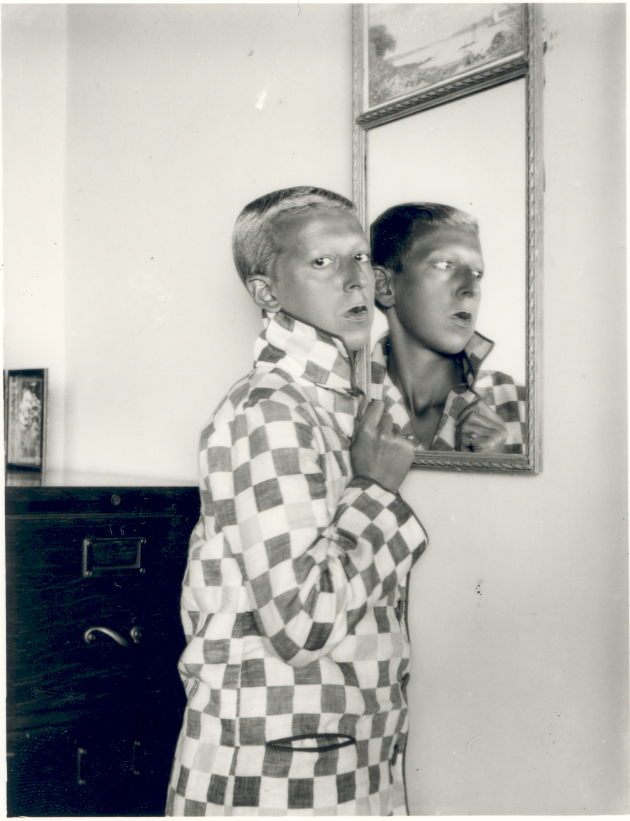

That’s bad, but it’s also just another day in the news for most readers of the Times. To really get a sense of the difference that I’m talking about, take a look at the photo that accompanied the Times story.

Compare this inert photo of car bombing in Baghdad with any of the images from Boston being circulated through the US papers. Two burned out cars are the center of the inaction, while kids and adults stand around as if wondering how to salvage a part of two. The image has all the emotional urgency of a junkyard, and no wonder: there is no trace of the dead and wounded, while those in the scene appear to be bored rather than acting as if they were in any danger.

The casualness and indifference of those standing around the metal carcasses suggests that this scene is merely a waning curiosity. It is a portrait of past violence, but violence that is unexceptional. Cars get blown up, just like they get into other accidents. Showing only damage to property, lacking pain, suffering, or any other emotional intensity, and suggesting that those at the scene are without any risk of being harmed themselves, this is what happens when a disaster is coded as an event that is not an emergency.

I don’t fault the coverage of the Boston bombing for doing everything differently: for showing suffering, action, anguish, and much more. And earlier in the war in Iraq there were photos, including some award winners, that did communicate the violence and terror that was brought down hard on the people living there. That’s what should be happening. But what also has happened is that the US has from the start abandoned large civilian populations to the horrors of war, and now too often the coverage of the continuing violence presents it not as a dramatic disaster requiring an extraordinary response, but rather as just another day in the life for those accustomed to living in a war zone.

The photos from Boston all scream EMERGENCY. They insist that this event is unique, exceptional, and deserving an immediate and comprehensive response. Like the pronouncements by the President and other public officials, they all demand justice for the innocent citizens cut down by a brutal terrorist attack. As Ariella Azoulay would say in The Civil Contract of Photography, they have made the suffering of those citizens into a political object: that is, an object of collective concern that mandates state action.

The photo from Baghdad, by contrast, says that nothing happening is that much out of the ordinary. There is no emergency claim. Any suffering is offstage or abstract and it falls short of meriting a specific political response. The fact of violence is being shown, yet the moral and political context remains largely invisible.

Thus, the photo inadvertently captures the real condition of those living amidst the violence in Iraq: they have been relegated to the condition (again, in Azoulay’s terms) of living on the verge of catastrophe. Neither being systematically sacrificed nor adequately protected, they are abandoned to a bare life of continuing, “low-level” violence.

It shouldn’t be surprising that one response of those trapped there is to treat bombed cars as a part of life. But the rest of us might take a moment to realize that all the horror experienced in Boston really is happening elsewhere, and much, much more often. Perhaps we can take a moment while our own hearts are torn to better understand how much others have to endure. And to recognize that the insanity will stop only when there is more solidarity among those who are suffering.

Photograph by Mohammed Ameen/Reuters.