This past Sunday marked the 75th anniversary of the explosion of the Hindenburg in Lakehurst, NJ. As we have indicated elsewhere, when it occurred on May 6, 1936, the event, prominently depicted in the above photograph, was immediately and subsequently identified as a gothic image of a “brave new world” that invited a bleak and cautionary attitude towards the catastrophic risks of industrialization and technology—a dystopian icon of an emerging, universalized, technocratic modernity. What is especially important to note is that the explosion of the Hindenburg, resulting in 36 fatalities, was neither the first nor the most deadly of such explosions—the explosion of Britain’s R-101 dirigible killing 46 passengers five years earlier on October 5, 1930. The key difference was that in the case of the Hindenburg the media was present with live radio coverage and, of course, we have the above photograph, which quickly became the iconic representation of the disaster.

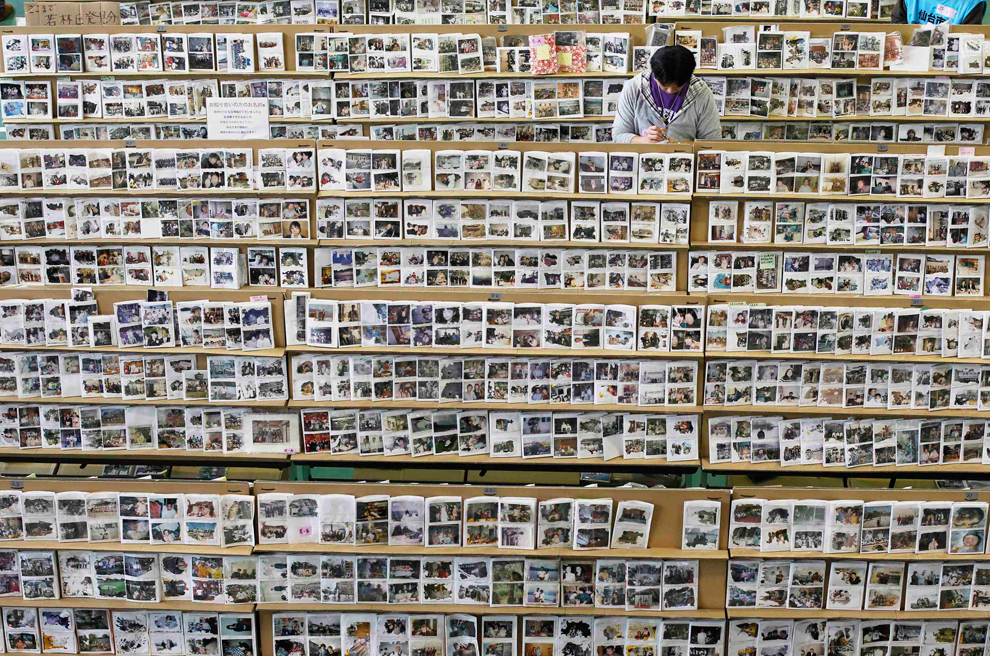

The last point is especially important, as it stands as a reminder of the centrality of the mass media in creating disasters. I don’t mean, of course, that the mass media cause disasters in a direct cause-effect fashion, but rather that what is recognized as a disaster is largely a measure of its status as a discernible “event” and outside of local and immediate experience. Such discernability is largely a function of the role that the media play in depicting and disseminating occurrences of one sort or another. As Rob Nixon has recently demonstrated in his book Slow Violence, tragedies that defy easy representation as a discrete occurrences—say disease and death caused across generations of the members of a community by toxic waste—are very difficult to cast as disasters because we simply cannot visualize their longitudinal effects. A graph marking deaths across time simply lacks the presence and verisimilitude of a photograph.

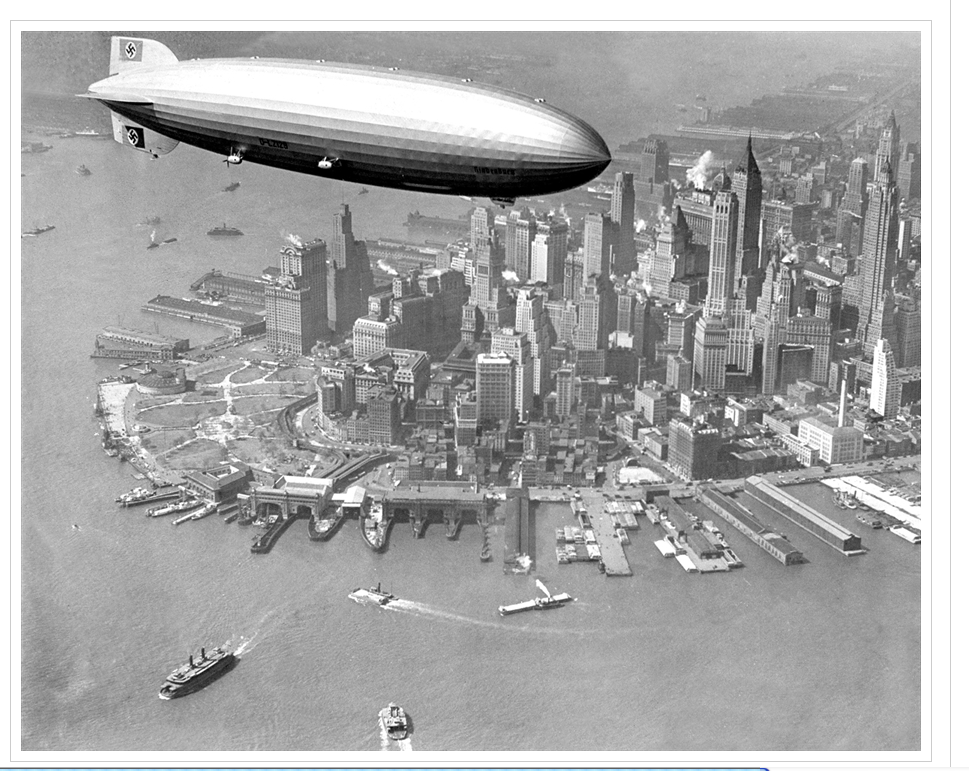

The anniversary commemoration of this event points to a different point as well. The iconic photograph above lacks any nationalistic markings of any kind. Although the name “Hindenburg” clearly designates this as a German airship, the photograph effaces that fact. It is impossible to say that this is the reason why this photograph quickly became identified as the icon for the event, but there are good reasons to believe that it didn’t hurt the cause, both because of the prevailing desire to downplay nationalist tensions between Nazi Germany and the United States, as well as the way in which such erasure made the photograph more about technology of a universalized modernity than about politics. But, of course, the extant photographic record suggests a different story. And so it is that the Atlantic frames its remembrance of the event not in terms of modernity’s gamble, but precisely in the context of international politics. So, for example, they begin with an image that shows the Hindenburg in all of its grandeur and magnitude, hovering over Manhattan. But what is most pronounced in the photograph is the swastika that sits on the tail of the vessel.

Several such images—few of which were originally seen, or at least prominently displayed in the media of the time—follow, carefully marking the national origins of the dirigible. And then, after a series of images that move the viewer through the ritualistic, everyday banality and catastrophic fatality of the attendant technological innovation of transatlantic air travel, it reinforces the nationalist origins of the whole event with photographs of a funereal scene. These photographs, replete with multiple caskets draped in swastika clad flags and Nazi salutes (images #31 and #32), are chilling in their effects, even if our contemporary reaction is marked by a presentist understanding of the horrors of Nazism that most viewers would not have been in a position to acknowledge in 1936.

The point is a simple one, but nevertheless worth emphasizing: photographs are always involved in a dialectic of showing and veiling. If we think of the iconic image in terms of how it is often captioned with reference to radio announcer Herb Morrison’s lament, “Oh, the humanity” it is easy to see how it fits within the logic of a dystopian, technological modernity. In short, it is a catastrophe that resists and challenges the positive resonance of modernity’s gamble. However, when we return the swastika to the tail of the dirigible in all of its prominence, and when we locate the event within the particular narrative of twentieth-century politics animated by Hitler’s Third Reich, the meaning of the icon is overshadowed by a much larger tragedy and its dystopian resistance to the positive affect of modernity’s gamble is mitigated if not altogether erased. It truly is a matter of what we see … or perhaps more to the point, what we are shown.

Photo Credit: Sam Shere/MPTV; AP File Photo