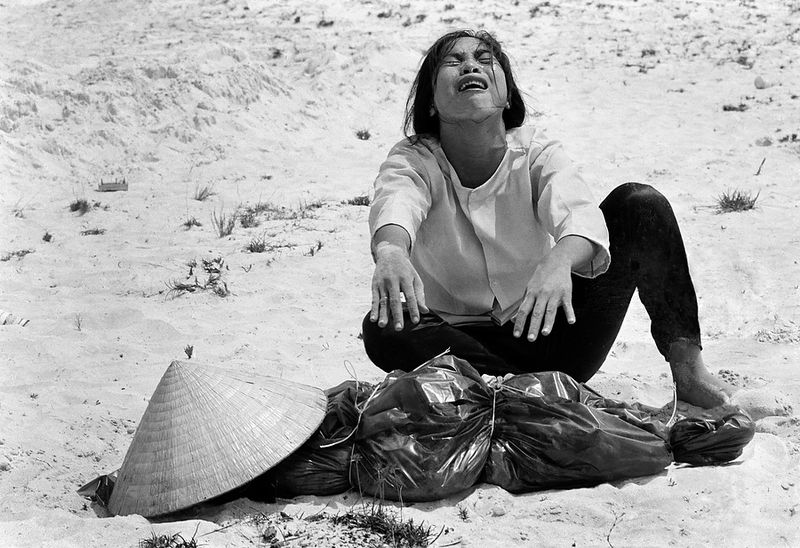

We typically forget that photography–and life itself–happens faster than the blink of an eye. And death, too.

The camera caught these Syrian rebels at the instant that they were bathed in fire from a tank blast. The moment is uncanny: they stand exactly as they were a a split second before, and yet the fire and shock wave is already unleashed upon them. Before, they had been picking up their weapons in anticipation of the tank that had been reported coming into the vicinity. Now, they are caught in the fraction of a fraction of a second before being killed. It’s as if the camera has isolated the invisible crack in time between cause and effect. And between life and death.

The men caught in the light died from the blast, while the one darkened to a silhouette escaped with minor injuries (if we don’t count the psychological damage). The camera uses both light and darkness, but there as elsewhere we depend most upon the light. Yet here the flames both reveal and kill, while the dark clouds of dust and debris in the next image obscure the rest of the dying while sparing the lone survivor. (The sequence of still images and a video are here.) As with war more generally, things are inside out or backwards, defying our ordinary sense of moral order. Being in the right and dedicated and prepared didn’t help one bit, and men who seem to be living in the fire without harm are about to die.

I won’t pretend to account for all of this incredible photograph, much less the remarkable sequence of images that comprise the visual story. Discussion is already underway–for example, at Michael Shaw’s prompting at BAGnewsNotes–and there are a number of issues in play. For the record, I don’t think there need be any moral failing in showing or marveling at or being moved by the image. The men and the moment are treated with respect, nothing disturbing beyond the inescapable fact of their being killed is shown, and that fact is so salient that there is little room to aestheticize the violence. In any case, one set of moral qualms can displace other resources for understanding and judgment.

To that end, let me make two quick points. The first is simply that the image is a perfect example of what Barbie Zelizer has identified as the genre of the About-to-Die photograph. I won’t summarize her extensive analysis of the genre, which you can read for yourself in her excellent book, About to Die: How News Images Move the Public. Suffice it to say, however, that there have been many images that confront the public with this unique moment, and that they can offer the spectator an opportunity to reflect on the event itself, and on how it is or is not tied to the narratives and other interpretive contexts that surround it, and how our knowledge and reactions depend on the camera and the larger apparatus of the news, whether for good or ill.

One can ask these questions any time, of course, but some moments seem more fraught with significance than others. One reason the about-to-die photo matters is that it reveals how any moment can be incredibly significant regardless of how it fits into a larger narrative, geopolitical conflict, or moral order. There is no other moment left for those in the photograph above, and by ignoring it one would demean life itself.

My second point is that the image above has both literal and metaphorical value, not least because of how it exposes a moment of unexpected rupture. I’m writing in the immediate aftermath of the attack on American consulate in Libya, and so it is easy to think of a flash point, and of the world changing in an instant, and of specific individuals going from life to death senselessly. With each of the four Americans who were killed at the consulate, there will have been a moment and then another and another where things went from bad to worse, until each got to the last, thin crack in time. With each attack, wherever it occurs, nations around the globe pass through a moment when hidden causes explode violently, and the idea that we can live within the flames is exposed as sheer illusion.

Photograph by Tracey Shelton/Global Post.