Sometimes a mundane photograph can capture historical conditions that usually are obscured by powerful habits of denial.

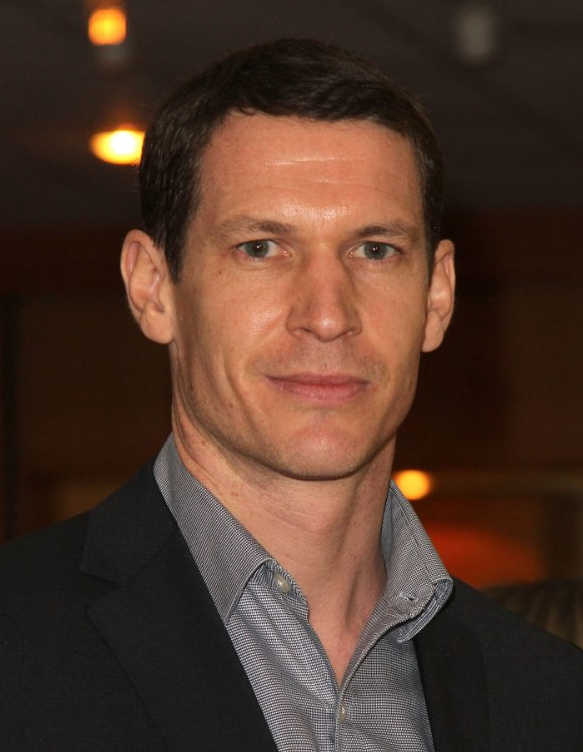

This image of a doctor reading an X-ray certainly seems part of the mundane world: that is, a world of cinder-block walls, florescent lighting, bottled water, and people standing around waiting. The trick of having the film replace the doctor’s face does add a touch of aesthetic flair, and the caption, which tells us that he is treating a rebel fighter in Libya, suggests that the scene is part of a larger historical drama, but all that is muted by the blue tone, the static figures, and the matter-of-fact demeanor of the orderly on the right. Even in an emergency room, there can be business as usual.

Except for the blood on that white glove. What could in fact also be a typical feature of medical practice here acts as a punctum, in the sense introduced by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida. It pierces our complacent response to touch us emotionally and awaken a more critical engagement with the photograph. Is that blood fresh? Even if not, why hasn’t he changed gloves? How dire is the situation? (It feels almost as if he has pulled that X-ray film out of the body cavity of the patient.) And why is he reading it in the hallway?

The last question begins to peel back the familiar response to the photo to expose something else. What kind of medical facility is this, where water has to come in bottles, where orderlies aren’t in uniform, where X-rays have to be read by the rude light of a corridor, and where the doctors are having to do diagnostic work amidst people milling about?

In The Civil Contract of Photography Ariella Azoulay uses the concept of being “on the verge of catastrophe” to describe the condition of a population that is deprived of resources and otherwise injured to the point where it is just above becoming a humanitarian disaster. Azoulay argues that Israeli governing techniques keep the Palestinians in the occupied territories and Gaza in this condition indefinitely. (Corroborating evidence includes Wikileaks documents quoted here.)

Her argument need not be limited to that single case, however. These controlled catastrophes appear banal enough that their visible harms fall short of the urgency and drama required for the intensive news coverage that might prompt outrage and action. Consider Azoulay’s first example of how this works, which is a photograph of a doctor reading an X-ray in Me’in village: “bare, dusty walls, a dirty space, the use of the natural light coming from the door due to the lack of electricity, the absence of proper equipment for examing X-rays, the conspicuously detached encounter between doctor and patient, the improvised clinic in which medical examinations are made amid people who are having a makeshift picnic after waiting for hours at the checkpoints” (p. 69). As you can see, it is not the same photograph and yet is it the same photograph as the one above, right down to what you can’t see here: the center of that photo dominated by a hand holding a blurry X-ray.

That film, at once opaque and yet capable of still being read by someone with suitable training and dedication, can stand for the photographs themselves. The conditions for response are less than ideal, but we can see what is there if we will but make the effort in solidarity with those who have been injured.

These photos are being taken all around the globe: photos of situations that are not and yet are the same. Libya may have a better future than the Palestinian past, but don’t count on it. Africa is littered with broken villages, regions, and states from decades of warfare and anarchy, and the larger forces at work in the Libyan war have much of the Middle East locked into political and economic stagnation. Libya may have been on the verge of catastrophe for decades, and it now may be trading one form of sustainable disaster for another.

What we can’t say, however, is that we never saw it coming.

Photograph by Odd Andersen/AFP-Getty Images.

0 Comments