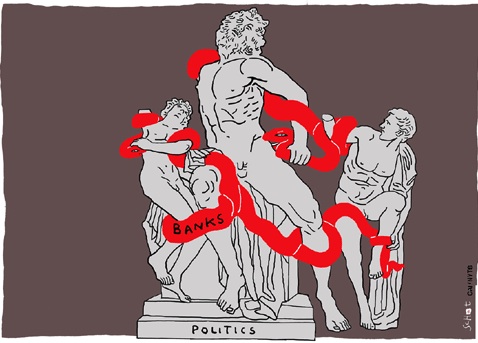

Yesterday the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit an all time high. Yet, as the New York Times reported, the response was relatively muted. There probably are several motives for being wary of the results, but one of the better reasons is that the good times on Wall Street are not quite so evident on Main Street.

As the Times noted, “The strength of the stock market is not strongly reflected in the real economy. Consumer confidence is well below the level it hit during the last high in October 2007. The unemployment rate was then 4.7 percent, compared with 7.9 percent now.” Not to put too fine a point upon it, but the Dow need not reflect the “real economy,” which would be the one that actually employs people. People, that is, who then can make a living, have less need of social welfare funding, and pay taxes that can fund the government and reduce the national debt.

Instead of assuming that all boats rise with the tide, we now need to think more carefully about how the labor and capital might or might not work together. The Times phrasing is instructive: there is the real economy and a virtual economy, and they are somehow close to one another and yet not necessarily working together or benefiting the same people. Not an easy thing to understand, which is why I like this photograph.

It’s from Japan, not New York, and the white line of the graph is from the Nikkei exchange, not the Dow, but these details are not relevant to what is being shown. The data and the people on the street are both reflected in a brokerage window–a transparent surface that, through the photograph, becomes a medium for reflection.

The image, like the reality it represents, is ambiguous, for it presents both dream and reality. On the one hand, labor and capital are seamlessly integrated into a single system. In that system, the relatively abstract, fluid investments are backed by the labor they fund and organize, which in turn prospers from that investment to acquire the many benefits of modern life–benefits such as good clothing, shelter, health care, transportation, communications, and all the rest.

That’s the dream, which has been realized more often than not. Oh the other hand, the photo also suggests that labor and capital can become strangely alienated from one another, so much so that the “real” work, lives, and interests of most people can recede behind a screen of financial activity that moves upward while they become increasingly secondary, ghostly, unreal. Indeed, they almost seem to be behind bars, as if crowded into a camp where they will become increasingly unknown, unheard, impoverished, and forgotten. In the process, “all that was solid melts into air,” and real and virtual realities change places. As in the photo, capital superimposes its image on labor, creating a society that has the form of a palimpsest, with the older values and social contract covered over by another picture priced to sell.

That doesn’t have to happen, but it is happening. The more that profits are disconnected from jobs, and the greater the disparities in income within corporations and societies, the more the virtual economy displaces material benefits. One reason it need not happen is that the same policies can benefit both capital and labor: for example, stimulus money from the Fed and other central banks can both support investment and create jobs. But that’s not a market solution, which is a problem in some quarters. So look again at the photograph: those white masks are another example of what happens when the side-effects of economic development are not checked by government regulation, and the fatigue evident on some of the faces is another clue that being driven by capital can have very real consequences that are not reflected in stock market data.

Another reason the virtual reality metaphor is so compelling is that a host of conservative pundits have been predicting an Economic Doomsday ever since Barrack Obama took office, and those dire warnings are repeated as fact again and again in online comment threads by lesser writers who insist that Obama has “wrecked the economy.” Yes, the economy was wrecked–in the final year of the Bush era, because of unrestrained greed and folly on Wall Street, and then kept that way for too long due to conservative pressure to reduce government stimulus policies. And Wall Street is prospering now because of the 4 trillion dollars the government provided to save the financial system, but don’t call that big government, or a stimulus, or money given to a bunch of takers who will only develop a greater sense of entitlement (as is said of all social services spending). In short, the ideologues’ history and judgments regarding the use of government monies are part of a virtual reality game very different from what actually happened. And why should they do otherwise if they never are held accountable: if you batted 0 for 50 in most leagues, you wouldn’t be sent back to the plate, but in Fantasy Politics you can have the same record and be the designated hitter.

One reason verbal illusions may be so easy to reproduce is that it is hard to visualize economic processes, and particularly those processes that involve inversions of value. But they can be visualized, at least in part or through a glass darkly, if we take the time to look.

Photograph by Yuya Shino/Reuters. For earlier posts on photos that superimpose financial data on human beings, go here, here, and here.

0 Comments