You don’t need to have a passport in order to be a U.S. citizen. But, as the brochure included with the new passport I recently received in the mail announced, “With Your U.S. Passport the World is Yours.” Well, sort of anyway. The first thing we learn upon opening the brochure is that this is an “Electronic Passport.” It’s not exactly an ankle bracelet, but “the information stored in the Electronic Passport can be read by special chip readers from a close distance.” One can only wonder what that last phrase might mean. The Department of State website assures us that it is “centimeters” and that the process is further secured by the latest “anti-skimming technology” (a fact that will no doubt impress every fourteen year old hacker paying attention). One less skeptical about how the current administration uses language and executive authority in the interest of national security to monitor its citizenry would probably not be paranoid, but then, as the saying goes, “just because you’re not paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.” Truth to tell, however, it was not the electronics that made this new passport stand out for me, but its visual presentation.

There is much to comment on here, not least the story of America’s “manifest destiny” that is told in monochromatic drawings and photographs on every page, captioned with quotations that extend from George Washington to John Kennedy and include scriptures from the “Golden Spike,” the Statute of Liberty, and a Mohawk “version” of a Thanksgiving Address. I will revisit this archive in the weeks ahead. Today, however, I want to take a look at the inside front cover of the passport as an allegory that contains and directs the iconography of the whole.

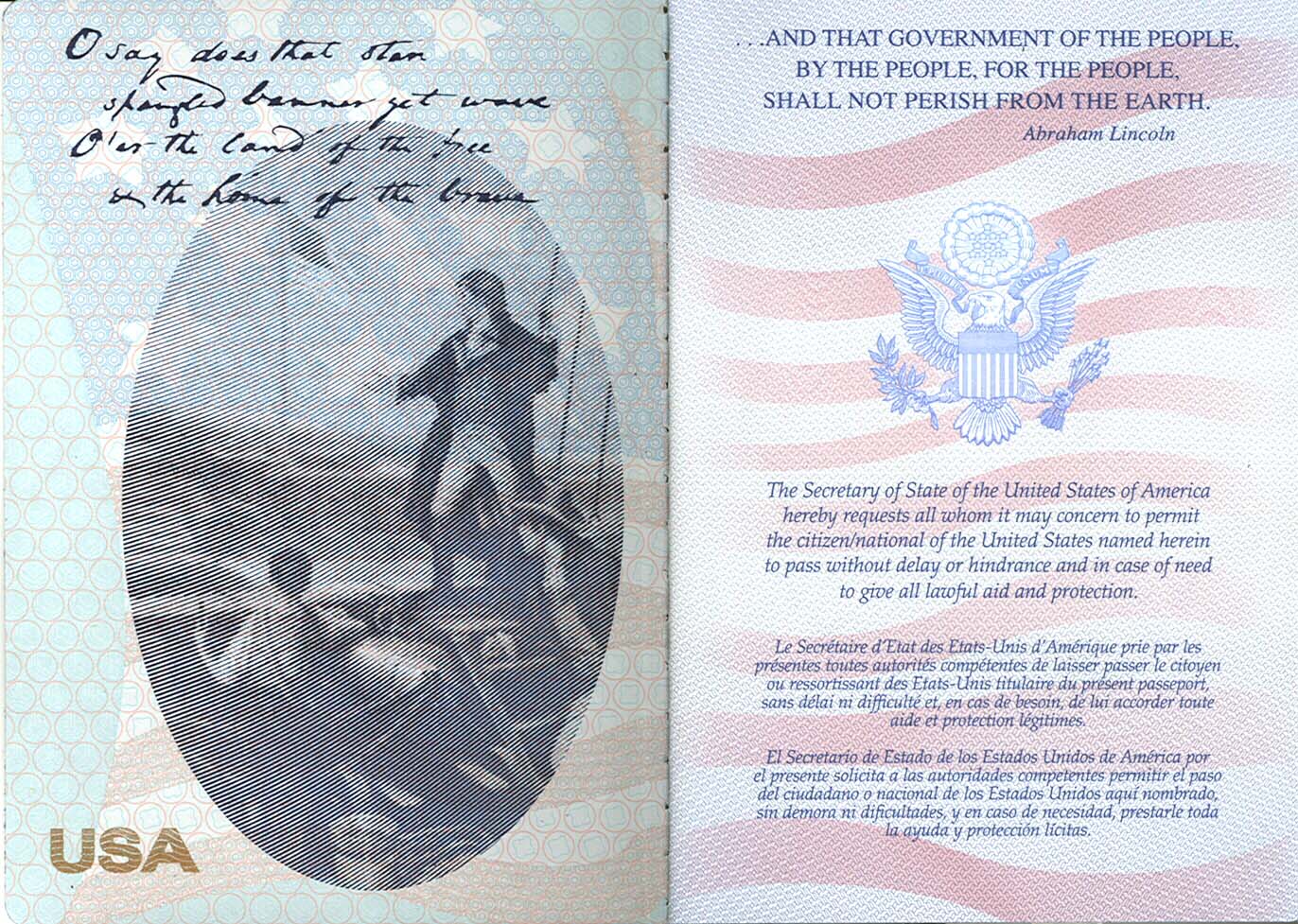

The first thing one encounters is a lithograph of Moran Percy’s 1913 depiction of Francis Scott Key gesturing to the garrison flag flying above Fort McHenry on the morning of September 13, 1814, following a massive, twenty-five hour long bombardment by the British Navy. Two weeks earlier the British Army had ransacked and burned down portions of the White House in Washington, D.C. Defending Baltimore Harbor was vital to repulsing a full scale British invasion and the 1,000 troops garrisoned at Forth McHenry proved to be up to the task.

The script written across the image is from Key’s poem “The Defense of Fort M’Henry,” and as most schoolchildren learn, it was subsequently set to music, renamed “The Star Spangled Banner,” and finally designated as the National Anthem in 1931. All of this might seem like trivial information but for the fact that references to the flag as it “yet waves” over the “land of the free and the home of the brave” became a fairly common trope in the wake of 9/11. There is no explicit mention of the more recent aerial attacks on the WTC and the Pentagon, of course, but the linkage between past and present is activated by a complex allegorical semiotic.

To see how, begin with the letters “USA” embossed in gold and placed on the lower left corner of the page. They stand apart from the painting and the script written across it, and yet they are very much one with both, a thoroughly modern caption for what purports to be a 19th-century imagetext. Indeed, boldfaced and uniformly blocked, the three gold letters stand in stark contrast to the pen and ink scroll that cuts across the image and bleeds onto the antique, elliptical matting of the painting. The aesthetic thus marks both the differences and continuities between then and now. Then we fought to secure our place among the world of nations, a newly birthed and independent nation-state emerging out of old world Europe, just as today we assure our continued sovereignty and security in (some might say hegemony over) a globalized, late modern world, now the gold standard among nations which, as the quotation from Abraham Lincoln on the right page intones, “shall not perish from the earth.”

Lincoln’s words operate in several semiotic registers. First, they are written in a contemporary font and in all capital letters. They thus function aesthetically to triangulate the relationship between Key’s 19th-century script and the modern typography of the golden inscription of the “USA.” As it was then, so it is now, and so it shall always be. The point is further reinforced as we realize that the entire two pages are printed across the image of the “Star Spangled Banner,” a flag tested in battle, and punctuated beneath Lincoln’s words with the imprimatur of the national seal. The eagle looks to the olive branch of peace and not the thirteen arrows of war, but we know how quickly that can change. Thus note how Lincoln’s words from the “Gettysburg Address” situate the overall image within the traces and contours of the U.S. Civil War, another challenge in a progressive history of such battles that have tested the sovereignty and resolve of the American nation. And thus the image that announces the U.S. Citizen to foreign lands, seeking passage “without delay or hindrance,” functions less as an introduction and more as an allegorical warning: for just as “confederates” were subdued then—and here one has to think of Sherman’s scorched earth policy—so now those who threaten the nation risk the wrath and retribution of all out war and occupation.

One might need to know a fair bit in order to develop this reading, but it is all common knowledge for anyone with the rudimentary understanding of U.S. history that one gets as part of their secondary school level high school education. We might wonder then who the primary audience for all of this is? Is it the heads of state implicitly identified by the Secretary of State’s “request” to “all whom it may concern,” repeated three times in English, French, and Spanish (what happens when one travels beyond the boundaries of these three Romance languages)? Or is it the “American people” who will have been “educated” to appreciate and perform the pious celebration of national strength and bravado as a ritual of national public memory—and to what particular ends? After all, as the brochure accompanying and explaining the passport declares, “With Your U.S. Passport the World is Yours!”

And there’s more. The words “With Your U.S. Passport the World is Yours!” touch yet another register, the blatant, brassy tone of the billboard, the hard sell. So if by ‘allegory’ you mean the aesthetic of a junk shop, with hatracks stacked beside mattresses and cutlery on top of washing machines, then that’s what you’ve got here. Put it together and what have you got? Bippety boppety boo, do you suppose?

Hi…Thanks for the nice read, keep up the interesting posts about peter moran..what a nice Saturday .

[…] in September I commented on the allegorical design of the new U.S. passports and focused attention in particular on the […]

I enjoyed this immensely and will blog this on facebook. I must agree that only those educated in the particular meaning of the symbols will understand what you meant but I guess for any consular official it would be easy to see the relationships. How great it is to be a citizen of the most prominent country on Earth today. However, I still have pride for mine and for yours, since half of my mom’s immediate family live there and I grew up in Maryland, and upon return to the Philippines I objected at first to being called a Filipino (all the while I thought I was American!).

[…] to the garrison flag flying above Fort McHenry on the morning of September 13, 1814″ (via No Caption Needed) and accompanied by a lyrical excerpt from our own national […]