Spring is a season of festivals: Chinese New Year, Carnival, Mardi Gras, and many, many more around the globe. A recent example is the Holi festival, which you can see in slide shows here and here. Such celebrations are photographic attractors, and for obvious reasons: brightly colored costumes, outlandish floats, dazzling light shows, and other displays of over-the-top theatricality in ordinary settings provide ritualized departure from winter’s humdrum routines, as well as plenty of eye candy.

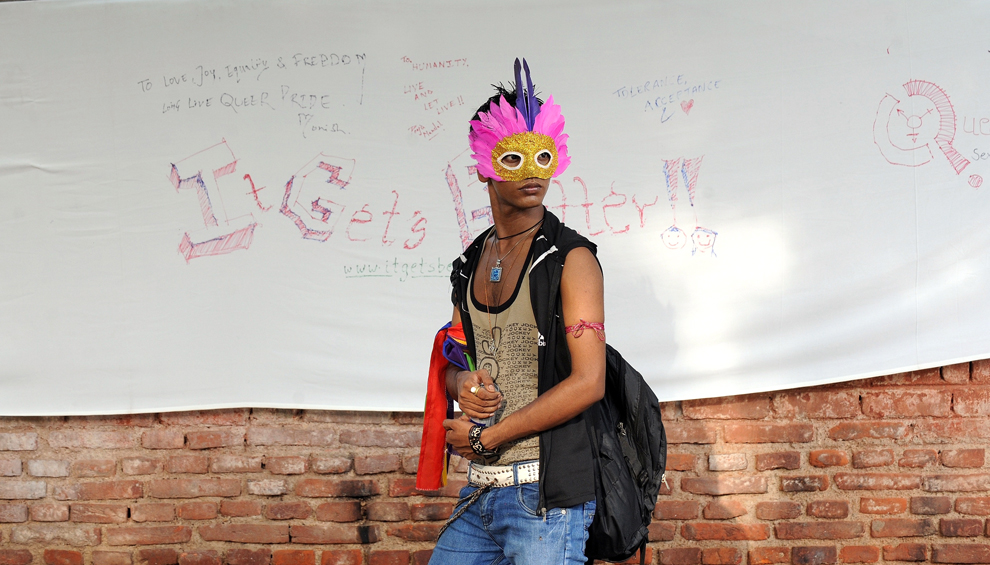

And once in a while, a moment of profound visual art. This stunning photo is a powerful example of how the camera can do more than capture the color and excitement of another culture.

Holi is a festival of color: individuals festoon themselves with paints while great crowds of people are drenched in colored powders of every hue. Colored water bombs explode, people sing, dance, and surge through the streets, and not a few may be imbibing intoxicants along the way. There also are vernacular theatricals replaying mythic stories, which is why, in the photo here, “Indian villagers from Nandgaon wait for the arrival of villagers from Barsana to play Lathmar Holi at the Nandagram temple famous for Lord Krishna and his brother Balram, in Nandgaon, India.”

Despite its aesthetic fidelity to the festival, this photo is quite unconventional. Many festival images feature thick washes of color, the energy and excitement of people in motion, and displays of massed exhilaration. By contrast, here we see the riot of color framed and subdued by the blue grey building, static poses instead of movement, individuals instead of a crowd, and attitudes ranging from bored to indifferent. And instead of being in the middle of the action, they and we are waiting for something to happen. And while that isn’t happening, we can sense that what is yet to come already is on its way being over: the red/orange/yellow/green stains look more messy than festive, and it is easy to imagine how the clothes will be washed, the walls washed down, and the bodies scrubbed to return everyone and everything to the ordinary time and business as usual the extends beyond the ritual celebration.

So the photographer isn’t showing us the festival that we would expect to see–an expectation determined by ideological habits that locate culture in the premodern present of a developing world known for being more colorful than productive. (See Reading National Geographic for a thoughtful account of how these habits are formed.) And when you think of it, the virtual experience that is being communicated by the typical photographs is a bit of a sham. Instead of all the noise and sounds and physical sensations of being pulled along by a crowd, intoxicated with sensual overload, freely yelling and laughing gleefully, we get—an image. Mute, and also lacking taste, smell, sound, or touch, two-dimensional, static . . . there isn’t much to get excited about. Of all the media that one might use to capture the experience of being caught up in a moment of collective delirium, photography probably is the worst choice you could make.

And that should tell us something. Several things, in fact. One is that the photographs that we do have must be working not merely in respect to the event being recorded, and not merely to reproduce that event, but rather in respect to a larger economy of images, one where they provide visions, or reminders, of social relations that are needed to fill out a larger conception of the world as picture. Another is that the visual encounter, and the virtual festival, might be doing more than we realize, for example, by stimulating imaginative reconstructions of events as if we were experiencing them through our full sensorium. (This is in part a psychological question, which I’ll leave to the scientists, but it also could be an interpretive claim.) A third point is that a specific image may seem more profound to some viewers (me, for example) as it comes to approximate the conventions of the Western fine art pictorial tradition. Most important, however, photography’s limitations when it comes to festivals could also provide a way of thinking about the role of ritual in human affairs.

And so we get back to the photograph above. It gives us a more institutional sense of theatricality, and with that, a basis for serious reflection on the relationship between drama and life. The guys in the picture are not merely villagers out of role, but rather acting like experienced troupers long accustomed to waiting backstage. And they are backstage, which provides a reverse shot on the explicit theatricality of the festival while miming a type of social theory developed by Erving Goffman and others.

And there is more: they are arrayed as if on stage, but in the sense of being posed for a painting. The four arched spaces could have been taken from a renaissance alterpiece, one now updated to include Hindu saints. Or they could be statues on a cathedral, giving us apostles, angels, and perhaps a defiant gargoyle on the inner left. Krisha has no need of a cathedral, of course, but some of his viewers might need a little help in seeing what is right in front of their eyes.

If you go back through the slide shows on Holi and the other festivals, it turns out that there are quite a few backstage shots. The photographers are doing what they have to do to file the story to compete in a marketplace of attention, but they are doing more than that as well. Precisely because the photo above is so static and composed, it gives us some insight into the carnival’s celebration of excess, play acting, and role reversals.

Or perhaps more than one insight. On the one hand, human beings are always on stage, always acting, always in character even when no one is supposed to be looking. And if waiting is part of the frenzy, then likewise the madness that is supposed to be released during the festival is always with us, no matter how mundane ordinary life may seem. On the other hand and at the same time, we retain an ability to step back, be still, carefully look at one another, and marvel at the strange, beautiful, fallen angels before us, just as they look and marvel at us. Indeed, all the distractions of color and action might be there in part to avoid seeing how much can be seen in ritual repose.

So look again. Notice that those in the photograh are not only being looked at, they also are looking: at others outside the frame, inwardly, and at us. As we study them, they study us, each mirroring the other.

Photograph by Manish Swarup/Associated Press.

1 Comment