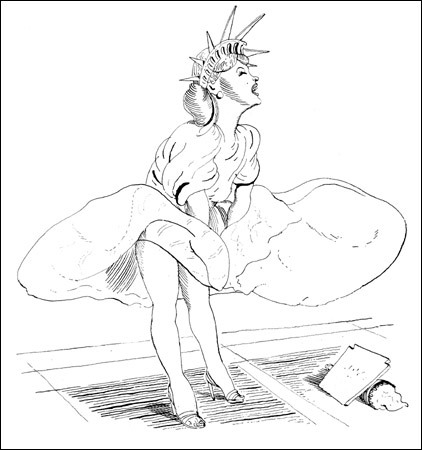

It may have started with this:

Search for “icon” on LexisNexis and you can quickly overload the browser with thousands of citations. And no wonder, the word appears continually these days in every section of the newspaper. Yesterday the Chicago Tribune reported, “At Hall of Fame, Day Dedicated to Two Icons, Not Controversy.” Who were the two titans of the game? Iron man Cal Ripken was one; the other was Tony Gwynn. A fine player, I’m sure, but not exactly a household name. He is, however, probably in the same league as Tom Snyder, who today was labeled a “late-night talk show icon.” A search reveals the same for a clerk in Cambridge, a banker in Arkansas, and just about everything in Australia. Not to mention tomato soup in the U.S. . . . Should we be surprised that there now also are “supericons” (Kate Moss, by one account)?

One might wonder why. My Northwestern colleagues Pablo Bockowski and James Webster have each done research that suggests one answer to the proliferation of “icon.” Very briefly, the combination of new media and intense competition for consumer attention can produce homogenized content. YouTube is an obvious example: of all those video clips seen by millions of viewers, one result is that a very few get tremendous circulation–dare we say they become iconic?–while most fade unseen in the desert air. As all media become focused on relaying what is currently popular to get their share of consumer attention, this phenomenon becomes the standard of significance while “repurposing” pops up as a new (and ugly) verb.

Here’s where “icon” comes into the picture. The homogenization thesis is a corrective to the fragmentation thesis, which says that incredible proliferation in media technologies and producers creates ever more finely segmented and isolated audiences. Thus, fragmentation and homogenization are countervailing forces that can produce mixed outcomes. We might speculate that the homogenization that can happen across producers and audiences can also happen within any topical category, audience, or sub-culture: amidst the information explosion within that “locality,” some few individuals will get a disproportionate amount of attention and thus seem to be representative of the category. Given these market forces, being notable and being well-known will seem to be much the same, so much so that one word might suffice for both. And so it is that anyone trying to claim that anything is worth our attention might say that it is iconic.

Thus, the same word can mark two related though quite different qualities. “Icon” can refer to anything that is recognized widely, such as the smiley face, or to any representative of a particular sub-culture, such as Tony Gwynn.

Have a nice day.