(“New York City celebrating the surrender of Japan. They threw anything and kissed anybody in Times Square.” Lt. Victor Jorgensen, August 14, 1945. National Archives, 80-G-377094.)

War continues to be a major topic of photojournalism and will be one of the topics of continuing interest on this blog, at least until the arrival of perpetual peace. While there are a number of fine studies of war imagery, I happened to ask myself today whether there are, or can be, photographs of peace. Obviously, art history archives are full of images–say, of the lion lying down with the lamb–that signify peace figuratively. Although photographs can acquire figurative and even allegorical meaning, I think that the realism, fragmentation, and other elements of the medium make it more difficult to represent peace. War is force, action, violence, destruction, pain–all things that can be communicated photographically. Peace involves the absence of war and the freedom to experience and enjoy other things, which then become the object of visual interest. If you define peace as necessarily involving sustainability and therefore justice, the problem gets even more complicated.

If you go to the Pictures of World War II at the National Archives Web site, you’ll see that one of the categories is “Victory and Peace.” There are ten photographs available there, and were a space alien to access them, it would have a hard time figuring out what either “victory” or “peace” mean. But those of us on Earth don’t do much better, do we?

This representational problem might be why the Times Square Kiss is an iconic photograph. (The public domain version is shown above.) John and I have much to say about it in No Caption Needed, although it now occurs to me that more could be added about how the image mediates the idea of peace. What I find more interesting, however, is another photo from the same collection, one that you probably haven’t seen before:

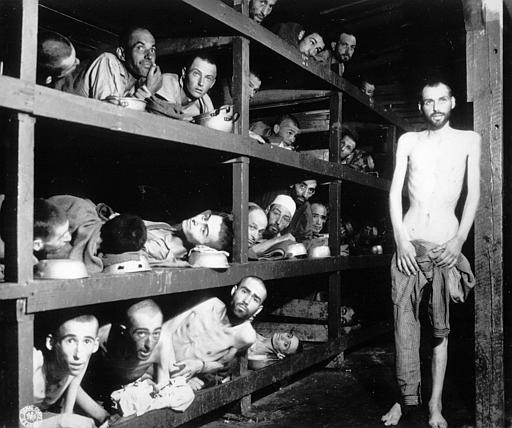

“Jubilant American soldier hugs motherly English woman and victory smiles light the faces of happy service men and civilians at Piccadilly Circus, London, celebrating Germany’s unconditional surrender.” Pfc. Melvin Weiss, England, May 7, 1945. National Archives, 111-SC-205398.

I find this to be a poignant image, particularly when compared with the Kiss. (Let’s leave the jokes about American and English eroticism aside for the moment.) Each photo is of a victory celebration in the public square of a great city, with spectators smiling at the camera to cue viewer participation in the scene. But instead of two sexually hot adults clenched in a powerful kiss, in this image we see mom getting a hug from one of the kids. And that’s the point that tears at me: they really are kids. I’m reminded of (and paraphrasing from distant memory) a scene at the beginning of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five: angry about the self-satisfied reminiscing by the narrator and his war buddy, the narrator’s wife spits out that they were just kids, children, when they were sent to fight and die. That’s what this photograph reveals so clearly (no caption needed). And so this really is a war photo after all.