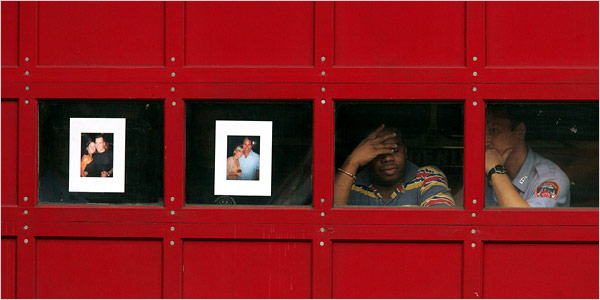

This is a hard photo of a bad day at the workplace:

At about 8 in the morning a former employee of the RiverBay Corporation gunned down a supervisor, then shot two other employees before taking the bus to a courthouse where he turned himself in. (Where would we be without good mass transit?) The photograph with the story shows the body of Audley Bent being brought out of the building at 12:50 p.m.

This is about as harsh an image of death as I want to see. The full body, including the head, wrapped up in that heavy tarp and strapped down tightly–right where the mouth and neck would be–well, there is no doubt that he is cold stone dead. The dramatic effect is heightened by the gurney and the technician’s gloves, which often are seen with a living victim who is being treated by med-techs while being ferried to an ambulance. Indeed, the brisk professionalism of the one, along with the casual attentiveness of the cop in the right foreground, make it seem as if this is just another accident.

Perhaps we’d like to think there might be some hope, but that huge, hulking, inert bag, stuffed with what is unmistakably a human body, crushes hope. Worse, look at how it matches up with the dumpster behind it: bag and trash bin appear to be the same dark green color and almost the same length. It’s as though the dumpsters are a row of coffins and the latest load from the apartment building is being taken to the next open bin. And what a cemetery: metal and concrete, everything rectilinear, featureless, and hard. The two living men could be prison guards. This industrialized back alley is no place to die, or to live.

The Bronx is better than that, of course, and you don’t take a dead body out the front door if you can avoid it. But the photograph does raise the perennial question about what images should or should not be published. Here one has little cause to complain about not being shown the dead.

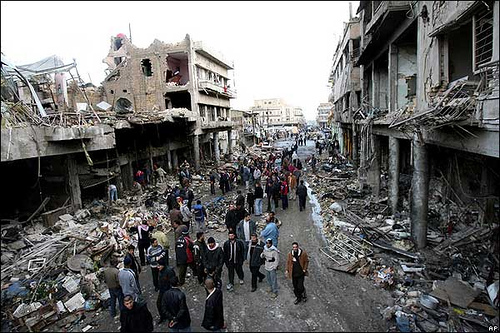

The photo also raises a question about how violence is framed. Had Audley Bent been gunned down in Iraq, he would have been “processed” in much the same way, but no image of the body bag would be in the newspaper. During wartime, the soldier’s death is rightly treated with respect, although that respect can include visual practices that also hide the nature of industrialized warfare while sacralizing war itself. Likewise, the fact that we are shown the body bag of a murder victim suggests that .38-caliber violence is somewhat taken for granted on the home front–as if it were another not-so-hidden cost of modern civilization like pollution or traffic congestion.

Or maybe I’m wrong about that. I hope so.

Photograph by Uli Seit for The New York Times.