Visual Democracy: Image Circulation and Political Culture

Northwestern University, McCormick Tribune Building

Friday, November 2

8:30 Coffee

9:00-10:30 Panel A: Ideology and Image

“An Aesthetics of Non-Reconciliation: Adorno on the Emancipatory Function of Art”

Michael Feola, Stanford University

“Reading the Architecture of Capitalism: Guy Debord and Ideology Materialized”

Richard Gilman-Opalsky, University of Illinois-Springfield

“Democracy’s Mirror of Mis/Recognition”

Jon Simons, Indiana University

10:45-12:15 Panel B: Publicity and Counterpublicity

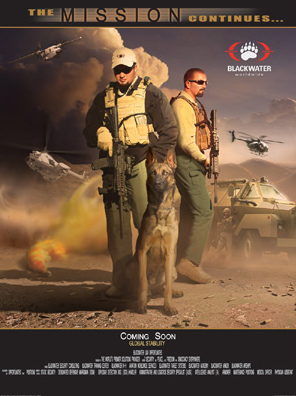

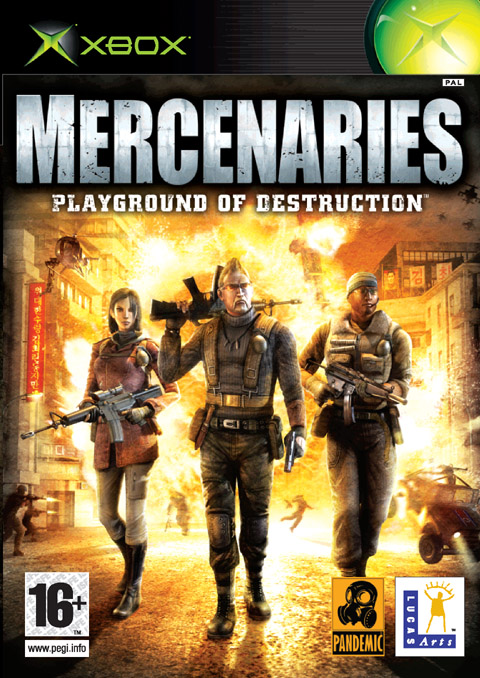

“Visual Rhetorics of Masculine Virtue in the War on Terror”

Gregory Spicer, California University of Pennsylvania

“Deviance on Television: The Democratizing Potential of the Headscarf”

Mirjam Gollmitzer, Simon Fraser University

“Private Eyes and Public Lives: Photographs by Garry Winogrand and Alison Jackson”

Elizabeth Ross, Northwestern University

12:15-1:15 Lunch (catered)

1:15: Welcome by Dean Barbara O’Keefe

1:30-3:30 Plenary A

“Mobilizing Art: The Visual Culture of US Intervention in the First World War”

David M. Lubin, Wake Forest University

“The Aesthetics of Democracy and the Dilemma of Kitsch”

Marita Sturken, New York University

4:00-5:00 Plenary B

“’Disappointing Vision: Hong Kong Cinema and Democracy’”

Ackbar Abbas, University of California, Irvine

Saturday, November 3

8:30 Coffee

9:00-10:00 Panel C: Power, Rights, and Visual Agency

“Visible Legitimacy: National Branding as a Visual System”

Melissa Aronczyk, New York University

“Family Photography and Human Rights”

Andrea Noble, University of Durham

10:15-12:15 Plenary C

“Rods From God: Missile Defense and Internet Advocacy”

Wendy Kozol, Oberlin College

“Globalizing Jerusalem: Architecture, Nation and Democracy at the Foot of Temple Mount”

Alona Nitzan-Shiftan, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology

12:15-1:00 Lunch (catered)

1:00-3:00 Plenary D

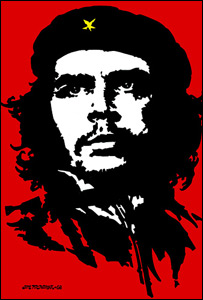

“The Power of Image: Reflections on the Specificity of Visual Impact”

Jean-Paul Colleyn, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales

“’To Sketch a Riot’: The Photographic Pharmakon in Late Colonial India”

Christopher Pinney, Northwestern University

3:30-5:30 Plenary E

“Photography and the Publicity of the Private”

Maren Stange, Cooper Union

“Overexposed Favelas: Urban Representations and Media Visibility”

Beatriz Jaguaribe, University of Rio de Janeiro

Sunday, November 4

8:30 Coffee

9:00-10:30 Panel D: Community, Memory, Media

“Preserving Democracy Without Circulation: Dorothea Lange’s War Relocation Authority Photographs”

Christina Smith and Karen Stewart. Arizona State University

“Visual Democracy, Public Memory, and the Case of Thessalonika”

Nancy Stein, Florida Atlantic

“Hurricane Katrina: A Photographer’s Notes On Photojournalism, Aesthetics, and the Market for News”

Aric Mayer, photographer

10:45-12:15 Panel E: Visual Culture and Democratic Participation

“Speaking of Photography: Visual Culture, Historical Images, and the Problem of Response”

Cara Finnegan, University of Illinois

“Drawing Them into Democracy: Cartoonist Carey Orr’s Visual Determinism”

Julie Goldsmith, Michigan State University

“’No Simple Thing to Do’: Interface and Atomic Citizenship in Operation Ivy”

Ned O’Gorman and Kevin Hamilton, University of Illinois

Conference organizers: Robert Hariman and Dilip Gaonkar

Sponsored by: School of Communication, Center for Global Culture and Communication, Program in Rhetoric and Public Culture/Department of Communication Studies

For information contact Patrick Wade <wpatrickwade@gmail.com>

All sessions are open to the public