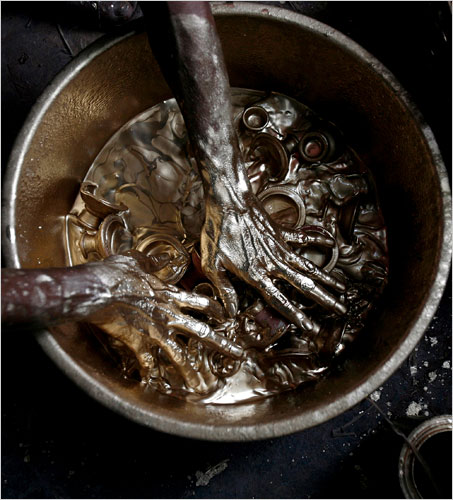

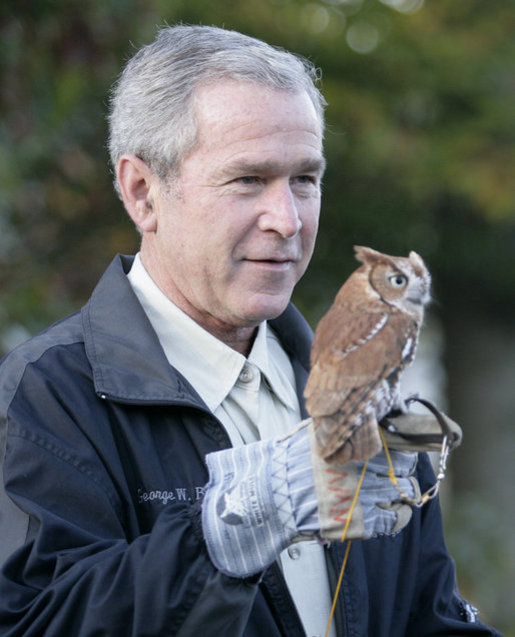

The picture is of a life size statute of “Samantha Stevens,” portrayed by Elizabeth Montgomery in the 1960s television show Bewitched, and arguably America’s most famous witch. Witches are typically cast as ugly and scary beings, and hence their prominence on Halloween. But Samantha Stevens was a beautiful and loving witch (as well, we might note, as an excellent housekeeper and the perfect wife and mother). For my generation, “Sam” Stevens stood in stark contrast to Margaret Hamilton’s portrayal of the “The Wicked Witch of the East” in The Wizard of Oz, and even to this day she maintains a fairly large fan base supported by websites, collectibles, and the like.

As a photograph the picture is really quite unremarkable. An altogether ordinary, slightly off-center “snapshot” of a statute; precisely the kind of image we might find in a private photo album documenting a family vacation. What makes the photograph notable here is that it was shot by a NYT photographer and that it appears in a NYT travelogue feature that regularly promotes places to which members of the upper middle classes might “escape” the rigors of everyday life, such as Aruba, St. Lucia, and Jamaica. Titled “The Ghost’s of Salem’s Past,” this slideshow promotes the devil may care attitude of Salem, Massachusetts, a quaint and quiet New England town that is represented by the NYT as operating at the juncture of the sacred and the profane, part historical landmark and part theme park. These attributions may not be inaccurate, as Salem relies almost exclusively on tourist traffic for its economic survival. And so it not only has to trade on its history, but it has to make witchcraft desirable – literally a commodity that consumers are willing to buy. And therein lies the problem, for the truly important lesson of Salem’s “history” should be addressed to its visitors as citizens and not as consumers.

Salem, of course, is the home of the Salem Witchcraft Trials of 1692, generally understood to be the most notorious (if not actually the first) “witch hunt” hysteria in the nation’s history. By the time the hysteria had ended over nineteen men and women had been hanged on Gallows Hill for allegedly practicing the dark arts, and another, octogenarian Giles Corey, was pressed to death under heavy stones, defying his executioners to his very end by taunting them to use “more weight!” The trials are regularly acknowledged as one of our darkest moments and are frequently pointed to as the first and most enduring challenge to what eventually emerged as the promises of civil liberty and social justice grounded in a commitment to religious toleration. Put differently, its legacy as a “usable past” is as a reminder to what can happen in the face of mass hysteria and the irrational fear of others within in our midst (which is not to say that all fears of the other are by definition necessarily irrational).

However much Salem attempts to retain a sense of its usable past, and thus to altercast its visitors as citizens with a responsibility to the sacred demands of civic democracy—and there are important efforts to do so, such as with the Salem Village Witchcraft Victims’ Memorial in neighboring Danvers—it nevertheless is confronted with powerful economic realities that animate its profane, consumerist, theme park sensibilities. So it is, that when the Samantha Stevens statute was dedicated in 2005, the television show being memorialized was described as “timeless” without even a hint of irony, let alone recognition for how its prominent placement in Salem risked overshadowing and domesticating the towns’ truly timeless and tragic history. It is as understandable as it is regrettable, at least for the residents of Salem.

But look at the picture one more time. Although shot by a professional photojournalist, it actually looks like it could have been taken by an amateur. Indeed, studiously so. The framing of the image—whether the statue or the man and child in the background—is off-center. Shot with a long lens but at a moderately wide angle, and with the shutter stopped down, the foreground and background are both in relatively sharp focus; the effect is thus to emphasize how cluttered the scene looks to be. And the exposure is all wrong as well, highlighting strong contrasts between the statue and the multiple backgrounds, and thus emphasizing shadows that make it very hard to know where one should direct their gaze. In short, it perfectly imitates what we might imagine to be an amateurish snapshot found in a personal photo album designed to document a family vacation. And as such, it invites the viewer to identify with it as a private consumer and not as a public citizen; come to Salem, it beckons, not to reflect upon your nation’s tragic past, but indeed, to “escape” that past by experiencing a “timeless” and happy fiction. What seems less clear are the stakes that the NYT has in all of this. Indeed, what is somewhat understandable, even bewitching, in Salem, MA, is both bothersome and bewildering when valorized by one of our leading institutions.

Photo Credit: Robert Spencer/New York Times; and with thanks to Stephen Olbrys Gencarella for introducing me to the carnivalesque atmosphere that pervades Salem, MA, and not just on Halloween, where it is the site of one of the largest public parties in the land, but to the ongoing struggle within Salem to negotiate the tension between economic survival and social justice.