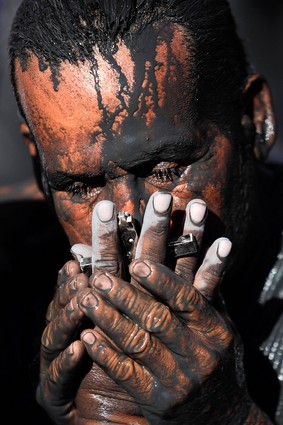

There is a type of visual experience that we might dub The Anthropological Moment. Most people haven’t taken a class in cultural anthropology, but they have paged through National Geographic, watched this or that documentary on the cable channels, or looked at a newspaper photograph such as this one:

As with much popular anthropology (and some would add, much anthropology until recently), one effect this image is able to reinforce the cultural presuppositions of the viewer. The caption certainly goes well down that road: “Act of faith . A man kisses a cross in the hand of a spiritual guide immersed in a small body of water that is believed to be miraculous, during the commemoration of the spiritual birth and physical death of the man known as El Nino Fidencio, in Espinazo, Mexico, Thursday. El Nino Fidencio or “The Child Fidencio,” the faith healer who lived in this dusty northern Mexican town in the 1930’s, is believed by the faithful to have worked miracles.”

You’d think the caption was written to cover the image with a blanket of words. A description of what we can see–a man kissing a cross in another’s hand–carries a second description of what we can’t see–the cultural meaning of the ceremony. And it is a ceremony: we don’t see people walking, conversing, working, or doing any of the activities of everyday life. Instead, the man is immersed within ritual, which in turn carries fantastic beliefs, which are at once foreign (been to Espinzao lately?) and exotic (seen a faith healer?). The key verb is “believed”: the water is “believed to be miraculous,” and the faith healer is “believed by the faithful to have worked miracles.” Such things are not what they are believed to be, of course, and so the “act of faith” is safely cordoned off by being placed in a ritual present that refers to a remote place and time where, then as now, people were deluded to the extent that they were encultured. So it is that a modern, secular, rational worldview is constituted through implicit contrast with folk customs that are marked as primitive, religious, and irrational.

It is not difficult to see how the photograph can work this way. (For example see Reading National Geographic by Catherine A. Lutz and Jane L. Collins. And, by the way, don’t conclude that National Geographic today is the same magazine they describe; in has changed remarkably, quite likely in a good faith response to their critique.) The mud-caked face and chalky finger coloring allude to thousands of images of African and other traditional cultures, and it is only on close inspection that one can discern that the man is clothed.

I’d like to think that there is something else there to be seen. For all that the caption does to shape comprehension, the photograph is a compelling depiction of emotional intensity. The image is one of great compression: the cropping concentrates our vision on the intensely evocative human face which is intensified further by the symbolic power of the cross, the communicative power of hands at once open and clasped, and the intimacy of a kiss. Not only are two bodies being brought together, but they are enacting a powerful moment of public intimacy. The one hand is open and yet needing to be taken up; when taken it confers a blessing that is both accepted, as if in prayer, and returned as he lovingly cradles the hand holding the cross. The man’s closed eyes suggest a vital interior life, as if he were drinking deep from water that sustains the soul.

Just as the close cropping can enhance the idea that this is a ritual practice, it also can suggest something quite different: the individualism and human dignity of Renaissance portraiture. (Thus, I can link the anthropological moment to one variation on a photographic Renaissance.) It that is too much of a stretch, it’s enough for me to believe (note the verb) that photographs can create an important tension between maintaining the public sphere and extending it, not only to include others but to challenge those within a modern mentality. If it is easy to see “culture” as the mark of the Other, an eloquent image also can remind us that the modern world can become spiritually and emotionally impoverished.

Culture both limits and connects. That is equally true in a “dusty northern Mexican town” and in a newspaper being read in a North American metropolis.

Consider in this context the German word for moment: Augenblick, or literally a blink of the eye. Like the aperture of a camera in reverse, the eye closes and opens. A moment is a hinged thing, containing an instance of blindness and of sight. Photojournalism’s anthropological moment is an invitation to both see nothing but our own self-conception confirmed, or to see others anew.

Academic disclaimer: These remarks don’t begin to account for the influence of anthropology on the visual arts, not least modern painting (Picasso’s masks became iconographic, for example) and film (Nanook of the North, Mondo Cane, and periodic takes on the Third World). Nor am I talking about the development of the subdisciplines of visual anthropology and visual sociology. Both are now Wikipedia entries, and suffice it to say that each field involves extensive discussion of the epistemological, political, and moral problems of representation. By contrast, the anthropological moment is something that most people encounter outside of the context of scholarly argument. They see the image without safeguards against ideological manipulation, but still having an opportunity for wonder and identification.

Photograph by Alexandre Meneghini/Associated Press.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by TU Cultural Studies. TU Cultural Studies said: RT @daniel_lende: The Anthropological Moment – On Photography & Anthropology: http://www.nocaptionneeded.com/2007/10/the-anthropological … […]