By most accounts Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima’s Mt. Suribachi is the most reproduced photograph of all time – ever! Claims to universality always invite dispute, but this one tends to go uncontested and for the life of me I can’t think of another photograph that might seriously challenge its primacy. Such reproductions have occurred not just in traditional print media, but on stamps (twice), commemorative plates, woodcuts, silk screens, coins, key chains, cigarette lighters, matchbook covers, beer steins, lunchboxes, hats, t-shirts, ties, calendars, comic books, credit cards, trading cards, post cards, and human skin, and in advertisements for everything from car insurance to condoms and strip joints. Additionally, it is frequently parodied in places like The Simpsons and it is a common trope in editorial cartoons where it draws its rhetorical force from both the power of its familiarity and the logic of substitution, whether to pious or cynical ends. And if there is a point to be made here it is that the image is regularly invoked to a wide range of patriotic and resistant or counter-cultural ends, thus marking the interpretive tensions invited and invoked by the original photograph.

All of this is to say that on the face of things there is nothing particularly noteworthy about Time’s appropriation of the image this week to frame and promote its “green” agenda in a special issue on the “War on Global Warming.” The original photograph works in three registers, emphasizing by turns a commitment to egalitarianism (the men are anonymous and without rank, while working together to a common purpose), nationalism (the raising of the flag on foreign territory is a symbolic expression of national sacrifice and victory), and civic republicanism (heroic sacrifice and commitment to the common good often commemorated in statuary designed to display civic virtues). Time’s usage of the photograph operates in all three registers as it substitutes a tree for the flag, and inserts color into what was originally a black and white image (as well as substituting a “green” border for the magazine cover’s traditional “red” border). The appeal, then, is to invoke a national effort of heroic proportions that will require equal sacrifice from every citizen in a war against an enemy that presumes to pose at least as large a challenge to world security as the axis powers. Just as the “greatest generation” brought the full force of its resources and resolve to vanquish fascism and make the world safe for democracy, so the image seems to say, the “greenest generation” can do battle to produce a greener, postcarbon world. The key difference, of course, is that here the enemy is ourselves, though that doesn’t really receive very much attention in either the photographic appropriation or in the lead article that accompanies it.

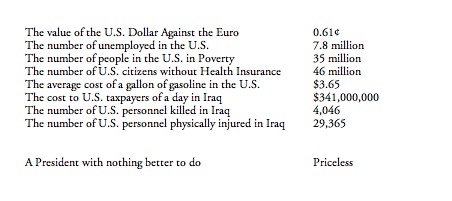

In short, the appeal of the cover image appears to be altogether innocuous. And given U.S. contributions to the problem of global warming, as well as our refusal to endorse the Kyoto protocols (even with their arguably flawed accords), there is no question that we need a serious and sustained national environmental policy designed to reduce our carbon foot print. And yet, there is something just a little bit troubling about the image. “Green,” we are told in something of a caption on the inside of the magazine, is the “new red, white and blue.” The lead article concludes, “The U.S. has enjoyed an awfully good run since the middle of the 20th century, a sudden ascendancy that no nation before or since has matched. We could give it up in the early years of the 21st—or we could recognize—as we have before—when a leader is needed and step into the breach. Going green: What could be redder, whiter, and bluer than that.” And there is the rub, for just as the title on the cover employs a martial metaphor to announce a “War on Global Warming,” so the photograph frames it—and all that follows—in terms of “the good war” remembered in not so subtle imperialistic terms.

We can (and should) debate the propriety of war metaphors as a basic strategy for dealing with global problems, but my interest here is in mapping out how the particular appropriation of the original photograph coaches an attitude that seems to rely on tired and clichéd conceptions of American exceptionalism. The key is in recognizing how the substitution of color for black and white on the cover is far more significant and complex than it might at first appear. Put simply, it is not just an appeal to be “green” (although it is that), but it also functions to translate the meaning of being “green” into a symbolic register that both defines environmentalism in terms of U.S. nationalism—“green is the new red, white, and blue”—and, more, makes something of an imperialistic fetish out of it.

If all we had was the Time cover to support this claim we might be rightly subject to the charge of over interpretation. But when we turn to the nine page cover story we find a series of what Time characterizes as “photo-illustrations” —not exactly the realist photographs of conventional photojournalism, but the medium of photography combined with creative photoshop skills that produce more or less surreal effects—that make the point visually over and again, ad nauseum.

The story begins with a full page color photo-illustration of a U.S. flag attached to a sapling that is growing out of a planter and being watered by an anonymous hand. Where the cover image substitutes the color green for the grey scale rendition of the red, white, and blue flag, here we get the reverse, a red, white, and blue flag substituting for ought to be green leaves; the anonymous hand completes the connection with the cover image as it stands in as a cipher for the anonymous soldiers. Two pages later we have another full page, color photo-illustration of two toddlers raising a green leaf up a flag pole on what would appear to be a mountain top. Nationalism and environmentalism are thus sutured in a naturalistic register, and all the more so as both are reinforced by the apt attention and simple innocence of children. That they appear to stand on a mountaintop draws the connection to Mt. Suribachi and further accents the natural, generational association between the “greatest generation” and the “greenest generation.” Turn the page once again and we come to a third full page color photo-illustration, this time of a sapling that appears to be exploding through a wooden floor that might otherwise contain it, its leaves bursting out in a full array of reds, whites, and blues as if part of a fireworks display on the Fourth of July. Whereas the first image shows a flag attached to a sapling, and the second shows nature being colonized by human hands to nationalistic ends, this third image completes the transformation as here nature has become fully and expressively one with the nation despite obstacles that might stand in its way.

Three other half-page photo-illustrations interspersed throughout he article underscore the claim to the “natural” connection between nationalism and environmentalism, as well as a more implicit appeal to American exceptionalism. The first and most stunning is of a tree branch with five green leaves, the most prominent one in the middle of the image growing in the shape of the United States. The last is a photo illustration of a man pushing a reel lawn mower as he sculpts the image of Old Glory in a giant lawn. Each underscores the sense in which both nature and nation are animated by the same impulse, whether driven by both geography (the “natural” boundaries of the map) or ideology (the histories and traditions marked by the “March of the Flag.”). It is the middle photo-illustration that makes the point most subtly, for here we have two men dressed in white and painting the white stripes and stars on the U.S. flag green: By contrast to other places in the article where “green” is substituted for “red, white, and blue,” and visa versa, here the two are imbricated with one another in a manner that makes being green a matter of nationalist identity and ownership, even as it implies the natural legitimacy (and thus authority) of national interest.

And lest we think that too much is being made of six images that occupy half the space of a nine page article that purports to be about how to solve the problem of global warming, we would note that there are only four 1¾ inch photographs of various alternative technologies for fighting global warming, each barely visible, let alone recognizable, and certainly neither informational nor memorable.

Let’s be green by all means, but let’s do it as citizens of the world, not as the dying vestiges of last century’s American exceptionalism with all that it implies.

Credits: Cover photo-illustration by Arthur Hochstein/Time and Joe Rosenthal/AP; Photo-illustrations by Anne Elliott Cutting and Frederick Broden; Petroalgae LLC. For a more detailed discussion of the Rosenthal “Iwo Jima” photograph and its history of appropriation, see No Caption Needed, pp. 93-136.

8 Comments